When computer screens around the world went blank on Friday, flights were canceled, hotels were unable to check in, cargo deliveries were halted and businesses were forced to turn to pen and paper. Initially, a cyberterrorism attack was suspected, but the reality was something much more mundane: a botched software update by the cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike.

“In this case, it was a content update,” said Nick Hyatt, director of threat intelligence at security firm Blackpoint Cyber.

CrowdStrike has a broad customer base, so the content updates were felt around the world.

“One mistake could have had disastrous consequences,” Hyatt said. “This is a perfect example of how intertwined modern society is with IT, from coffee shops to hospitals to airports. A mistake like this can have huge implications.”

In this case, the content update was tied to CrowdStrike Falcon monitoring software. Hyatt said Falcon has deep connections to monitor for malware and other malicious behavior on endpoints (in this case, laptops, desktops and servers). Falcon automatically updates to keep up with new threats.

“The automatic update feature released buggy code, and that’s where we are today,” Hyatt said. Automatic update features are standard across many software applications and are not unique to CrowdStrike. “The damage here is just devastating because of the way CrowdStrike has done things,” Hyatt added.

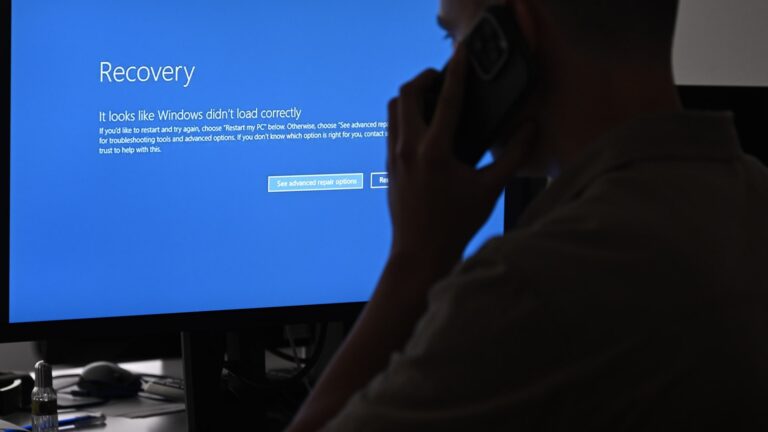

On July 19, 2024, in Ankara, Turkey, computer screens displayed a blue screen error due to a global communications outage caused by CrowdStrike, a company that provides cybersecurity services to the US technology company Microsoft.

Harun Ozalp | Anadolu | Getty Images

Although CrowdStrike quickly identified the problem and many systems were back up and running within hours, the cascading damage on a global scale is difficult for organizations with complex systems to easily reverse.

“I think it could take three to five days to resolve this,” said Eric O’Neill, a former FBI counterterrorism and counterintelligence officer and cybersecurity expert. “That’s a lot of downtime for organizations.”

O’Neill said the situation was exacerbated by the fact that the power went out on a summer Friday while many offices were empty and there was a lack of IT personnel to help solve the problem.

Software updates should be rolled out in stages

O’Neill said one of the lessons learned from the global IT outage was that the CrowdStrike update should have been rolled out in stages.

“What Crowdstrike did was push the update out to everyone at once, which is not the best idea. They should send it to a group of people and test it. There’s a level of quality control it has to go through,” O’Neill said.

“They should have tested it in a sandbox or in different environments before releasing it,” said Peter Avery, vice president of security and compliance at Visual Edge IT.

He foresees the need for additional safeguards to prevent future incidents of this kind of failure.

“Companies need to have proper checks and balances. It could be just one person who decided to push this update, or someone else picked the wrong file and ran it,” Avery said.

In the IT industry we call this a “single point of failure,” meaning an error in one part of a system can cause a technical disaster across an industry, function, or interconnected communications network, setting off a massive domino effect.

Calls for building redundancy into IT systems

Friday’s events may prompt businesses and individuals to step up their cyber-preparedness.

“If you look at the bigger picture, it shows how vulnerable the world is. It’s not just cyber or technological issues. There are a whole host of phenomena that can cause power outages. A solar flare, for example, can take down communications and electronics,” Avery said.

Ultimately, Friday’s meltdown isn’t an indictment on CrowdStrike or Microsoft, but on how companies view cybersecurity, said Javad Abed, an assistant professor of information systems at the Johns Hopkins University Carey School of Management. “Company executives need to view cybersecurity services not just as a cost, but as a critical investment in their company’s future,” Abed said.

Companies need to do this by building redundancy into their systems.

“A single point of failure shouldn’t stop a business, but it did,” Abed said. “You can’t just rely on one tool, Cybersecurity 101.”

Building redundancy into corporate systems is costly, but what happened on Friday is even more costly.

“I hope this serves as a wake-up call and causes business leaders and organizations to think differently and rethink their cybersecurity strategies,” Abed said.

What to do about “kernel level” code

Nicholas Rees, a former Department of Homeland Security official and lecturer at New York University’s SPS Center for International Affairs, said that on a macro level, it’s fair to place some organizational blame on the enterprise IT world, which often views cybersecurity, data security and the technology supply chain as “nice-to-haves” rather than essentials, and on a general lack of cybersecurity leadership within organizations.

At a micro level, Rees said, the code that created this mess is kernel-level code, which affects every aspect of how a computer’s hardware and software communicate. “Kernel-level code should be subject to the highest level of scrutiny,” Rees said, noting that approval and implementation should be entirely separate processes that involve accountability.

This is an ongoing problem across an ecosystem filled with vulnerable third-party vendor products.

“How do you look at the entire ecosystem of third-party vendors and figure out where the next vulnerability is? It’s almost impossible, but you have to try,” Rees said. “Unless you address the number of potential vulnerabilities, it’s a certainty, not a possibility. You need to focus and invest in backups and redundancy, but companies say you can’t spend money on something that may never happen. This is a tough case to make.”