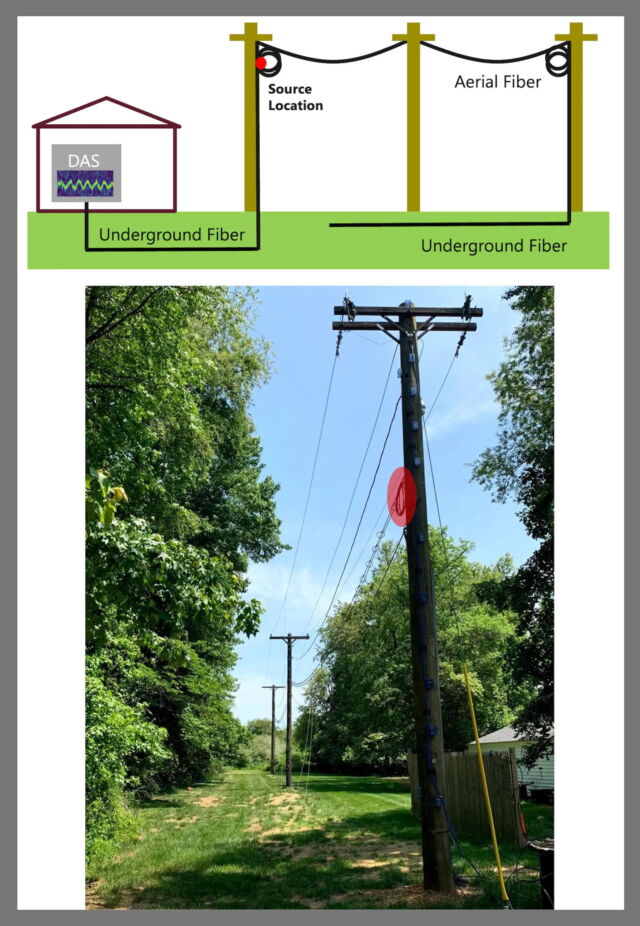

One of the world’s most unusual test benches stretches above Princeton, New Jersey. This is a fiber optic cable strung between three utility poles, which runs underground and then connects to an “interrogator”. The device fires a laser through a cable and analyzes the reflected light. It can pick up small fluctuations in light caused by seismic activity and even loud sounds like a passing ambulance. This is a new technology known as Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS).

Because DAS can track seismic activity, other scientists More and more people are using it to monitor earthquakes and volcanic activity. (In fact, buried systems are so sensitive that Detects people walking or driving in the sky.) But Princeton scientists stumbled upon a rather…noisy use of this technology. In the spring of 2021, Sarper Ozaler, a physicist at his NEC laboratory that runs the Princeton testbed, noticed that: Strange signals in DAS data. “We realized something strange was happening,” Ozaral said. “It shouldn’t be there. A unique frequency was buzzing everywhere.”

The research team suspected that the “something” was not a rumbling volcano. new jersey–However, the cacophony of a huge swarm of cicadas that just emerged from underground, the population Known as Brood X. Her colleague suggested she contact Jessica Ware, an entomologist and cicada expert at the American Museum of Natural History, to find out. “I was watching cicadas and was going around Princeton collecting cicadas for biological samples,” Ware says. “So when Sarper and the team showed what they could actually do; listen I was very excited because the sounds of the cicadas and their patterns matched somehow. ”

The list of things that DAS can monitor is rapidly growing and insects are also being added. Thanks to their specialized anatomy, cicadas are the noisiest insects on the planet, but all kinds of other six-legged species, like crickets and grasshoppers, also make loud noises. Entomologists may have stumbled upon a powerful new way to constantly monitor species from a distance using fiber optic cables. “One of the challenges we face now that insect populations are in decline is the need to collect data about how big the population is and which insects are where.” Ware says Mr. “I think this type of remote he can be really creative once he understands what he can do with sensing.”

DAS is all about vibrations, such as the sound of cicadas or the movement of geological faults. Fiber optic cables transmit information by emitting pulses of light, much like high-speed internet. Scientists can use an interrogation device to shine a laser into the cable and analyze the tiny amount of light that bounces back to the light source. Since the speed of light is a known constant, it is possible to determine exactly where a particular disturbance occurs along the cable. If something hits the cable at 100 feet, the light will take slightly longer to return to the interrogator than if it occurred at 50 feet. “The fiber allows him to turn every meter more or less into a kind of microphone,” Ozalal says.

Journal of Insect Science/Entomological Society of America

Ozalal’s team focused on the loop of cable on top of one of the utility poles, seen in the photo above. (The loop is highlighted in red.) “If the fiber is straight, the sound interacts with the fiber only once and then continues to travel,” Ozalal says. “But when you have a coil, the same signal travels down the fiber over and over again.” This allows his fans in the crowd to use multiple microphones instead of recording the concert on their smartphones. The sensitivity of the system will be greatly improved, such as when recording concerts.

When Brood X emerged in the spring of 2021, Ozharar’s DAS system happened to be eavesdropping. This kind of “periodic cicada” occurs underground and, depending on the species, he emerges for mating every 13 or 17 years. “We don’t know exactly why, probably because of climate change, but there are some laggards, some populations that came out earlier and some that came out later than their metabolic timing,” Ware said. he says. “If we had a way to monitor them over time, that would be very helpful.”

Male cicadas have organs called timbales that vibrate like drums to produce their unmistakable song. Each species has its own song variations that allow suitable males and females to find each other. Additional information is also embedded in the sound. Men tend to call during the hottest hours of the day, which is also costly in terms of energy. This allows the female to assess the quality of her mate. The female wants to choose the most suitable male so that she can pass on the primo genes to her offspring.

Hence all the noise. DAS can be heard from the beginning of its emergence, through its peak, to its decline as mass mating rituals decline. Entomologists can determine cicada population numbers because the amount of noise is a reliable indicator of cicada numbers. They can even see the effects of temperature. As temperatures rise, male cicadas become less vocal. “If you look back over his five days of monitoring data, you can see that when the temperature is a little cooler, the frequency of his calls varies slightly in hertz,” Ware said.

Fiber optic cables are already everywhere, just waiting for scientists to take advantage of them. Of course, they are abundant in cities, but they can also travel between cities, which is useful for entomologists who want to monitor insects in more rural areas. “We use them simply to send data (0s and 1s), but they can do a lot more than that,” he says Ozharar. “Therefore, fiber sensing will become increasingly important and more widely used in the near future.”

No one is saying DAS will replace other methods of monitoring insects. Fiber optics are popular, but they are not. wherever. Instead, DAS can complement other technologies.field called bioacoustics is already using microphones to listen to species living in remote areas, sometimes with the help of AI, to analyze the data. This method is useful for checking data from fiber optics. Scientists are also experimenting with “environmental DNA.” eDNAfor example, using an air quality station collect biological materials Floating in the designated area. And entomologists like Ware still need to collect specimens from the field to physically examine the health of individual animals.

“What’s really cool about this new technology is that this one cable can probably cover many kilometers and all the information is recorded in one device,” said Entomologist and researcher at the California Academy of Sciences. says Elliott Smeds. B.Sc., who was not involved in the research. “We’re finding that we don’t even know what the baseline is for tracking how many of these species are doing, especially now that insects are in decline. The biggest obstacle is is about keeping enough shoes on the ground to collect this kind of data.”

The key is to adapt DAS to monitor species. it’s not The noisiest insect on earth. “In this case, it was very obvious that these were cicadas, because all of a sudden, millions of them came down. I’m not exaggerating,” Ware said. “But in most cases, the populations of each species are much smaller. It will be an interesting question to know whether we can actually tell the insects apart.”

This story was originally wired.com.