Dhaka, Bangladesh – Every time Mosamat Maina enters the dengue ward at Magda Hospital in Bangladesh’s capital, sadness and fear grip her heart.

The 23-year-old has only been working as a cleaner at the hospital for about a month, but the only reason she took the job was because her sister, Maria Latona, died of dengue fever while working as a cleaner at the hospital last month. It is. Same ward.

“My sister worked hard for months during this year’s dengue outbreak and eventually contracted the disease. After her death, the hospital authorities offered me a job,” Maina said. told Al Jazeera.

“Our family was shocked by Ratna’s death, but I accepted the offer even though I was very scared as I was out of work.”

Bangladesh is experiencing its worst dengue fever outbreak in history, with hospitals filling up and the death toll rising. Last Wednesday, the country recorded 24 deaths from the mosquito-borne disease, the highest number in a single day.

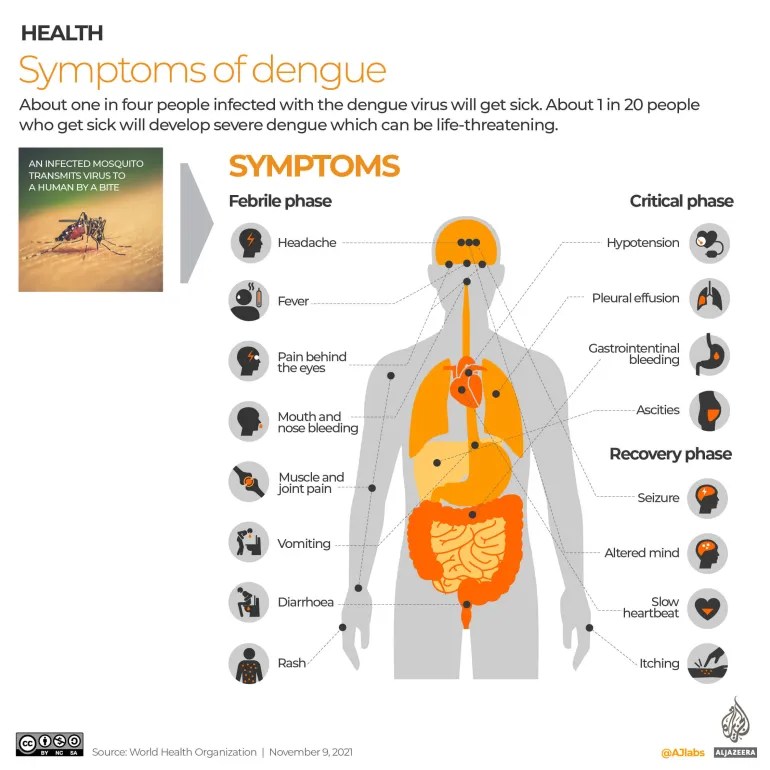

The disease cannot spread from person to person, but mosquitoes that bite an infected person can become carriers and transmit dengue fever to other people they bite. That makes places with high concentrations of dengue patients, such as the hospital where Maina works, more dangerous for people who aren’t yet infected.

Health experts are on alert because dengue fever typically subsides in the South Asian region once the annual monsoon rains end by the end of September.

As of Monday, at least 1,549 people had died from the disease in Bangladesh, including 156 children aged from newborn to 15 years old, bringing the total number of dengue infections this year to 301,255, according to the government’s health directorate. are doing. (DGHS).

This record death toll is almost five times higher than last year’s 281 deaths, which was the highest single-year death toll in Bangladesh’s history until this year’s outbreak. The highest number of cases in a year so far was 1,01,354, reported in 2019.

“We have never seen a dengue outbreak on this scale,” Dr. Mohamed Niatuzzaman, director of Magda Hospital, told Al Jazeera, adding that patients were pouring in from all over the densely populated country. . “It is very unusual to have so many dengue cases in November.”

Occurrence of “epidemic” proportions

Until now, dengue outbreaks have been largely confined to densely populated urban centers such as the capital Dhaka, which is home to more than 23 million people. Experts say the disease has reached all districts this year, including rural areas.

According to DGHS data, 65% of the cases reported this year were from outside Dhaka city, marking the first time that Dhaka had fewer cases than other parts of the country.

Sohaila Begum arrived at Mugda Hospital from Patuakhali South district with her 11-year-old daughter, who had been suffering from a high fever for more than a week. They are sleeping in the hospital corridors because there are no available beds.

“When her fever worsened, doctors at the district hospital told us to immediately take her to a good hospital in the city,” she told Al Jazeera, adding that her daughter’s situation had improved. added.

“We came to Dhaka, but we are running out of money. Everything is very expensive here. If we stay any longer, we will be in trouble.”

Dr. ANM Nuruzzaman, a public health expert and former DGHS director, told Al Jazeera that this year’s outbreak is nothing short of an epidemic.

“The problem is that the severity of dengue fever has disappeared from the public and media attention as the country is experiencing political turmoil ahead of the next election,” he said.

Bangladesh is scheduled to hold a general election on January 7, amid political uncertainty and violence gripping the country. The main opposition party, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), is demanding the removal of the ruling Awami League government and the installation of an interim government to ensure freedom. and fair public opinion polls.

“Dengue fever has become a serious crisis because the pattern and severity of the disease is changing and getting worse. The government should have declared a public emergency a long time ago,” Nuruzzaman said. Ta.

Government officials say they are doing everything they can to stop the spread of dengue fever and that declaring it a public emergency or epidemic would not have made much of a difference.

“All public hospitals across the country have been directed to open special dengue wards in early August. The Ministry of Health has also allocated an emergency budget to fight the outbreak,” said DGHS Head of Non-Communicable Diseases. Dr. Mohammad Robed Amin told Al Jazeera.

“The problem is that our health care system has serious limitations because we have a large population and it is almost impossible to ensure health care and treatment for everyone,” he said. .

Amin said the number of infections and deaths this year is “extraordinarily high” for several reasons. “The first and most important reason is the overwhelming prevalence of the Den-2 strain of dengue among patients,” he said.

There are four types of dengue fever: Den-1, Den-2, Den-3, and Den-4. After infection, a person develops immunity to some types of dengue but not to others.

“Den-3 strains have been prevalent in Bangladesh for the past few years, and people have developed immunity against them. However, this year, more than 75 per cent of patients were diagnosed with Den-2 and died. “Nearly all of our patients were affected by this particular strain,” Amin said, adding that studies have found that Den-2 is even worse when traced to Den-3. Depending on the number of years of infestation.

Another reason for the high death toll is the outbreak in rural areas.

“This year, the disease has spread across the country, and there is a huge lack of medical facilities in rural areas. Moreover, most people are unaware of the seriousness of the disease. If they do not receive treatment on time, It can be deadly. And it’s happening in many areas.”

What was the cause of the record death toll?

Meanwhile, entomologists say they may have found a possible reason behind this year’s record outbreak.

Kabirul Bashar, a professor of medical entomology at Jahangirnagar University in Bangladesh, told Al Jazeera that dengue peaked in October last year, killing 86 people, changing the pattern of dengue subsidence by September. he said. The year before that, in 2021, there were 22 cases.

“We raised the alarm last year that the pattern of this disease itself is changing. Now, dengue is no longer a monsoon-related disease, but a year-round one,” said the country’s National Anti-Dengue said Bashar, who is also the committee’s only scientific expert.

The scientist said climate change is changing patterns of temperature, rainfall and other natural phenomena.

“We are currently experiencing almost monsoon-like rains from October to early November. That changes the reproduction and life cycle of Aedes mosquitoes,” he said, referring to the type of mosquito that transmits dengue fever.

Dengue fever is prevalent mainly in South and Southeast Asia from June to September. During this time of year, stagnant water provides ideal habitat for the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Aedes aegypti usually breeds in clean water and feeds during the day.

But in a breakthrough, Bashar, who has been studying mosquitoes for more than 20 years, discovered that mosquitoes now breed in dirty sewers and salty seawater.

“So, on the one hand, we have unusually consistent rain during the off-season, providing an ideal environment for mosquito breeding, and on the other hand, the mosquitoes are expanding their breeding horizons. It’s a double whammy.” he told Al Jazeera.

Entomologists also found that the two most widely used insecticides in Bangladesh, malathion and temephos, have become “no longer useful” against the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

“These two insecticides have become semi-insecticides and have lost their effectiveness against mosquitoes due to the development of resistance,” said Professor Morande Golam Shallower of the National Institute of Preventive and Social Medicine.

“Unfortunately, most urban businesses across the country still use these two types of insecticides, which do little to control mosquito populations.”

Bashar said the government needs to come up with a serious five-year plan to curb the spread of dengue fever and eventually eradicate the Aedes aegypti population.

“If such a plan is not activated immediately, the disease will only get worse in the coming years,” he said.

Back at Dhaka’s Magda Hospital, Maina was overwhelmed by an unusually long dengue outbreak and began to regret her decision to work as a cleaner.

“We thought that dengue fever would go away once the rainy season ends, but patients are coming in every day. Forget about beds in wards, there is no space even in hospital corridors,” she told Al Jazeera.

“I’m afraid I’ll end up like my sister.”