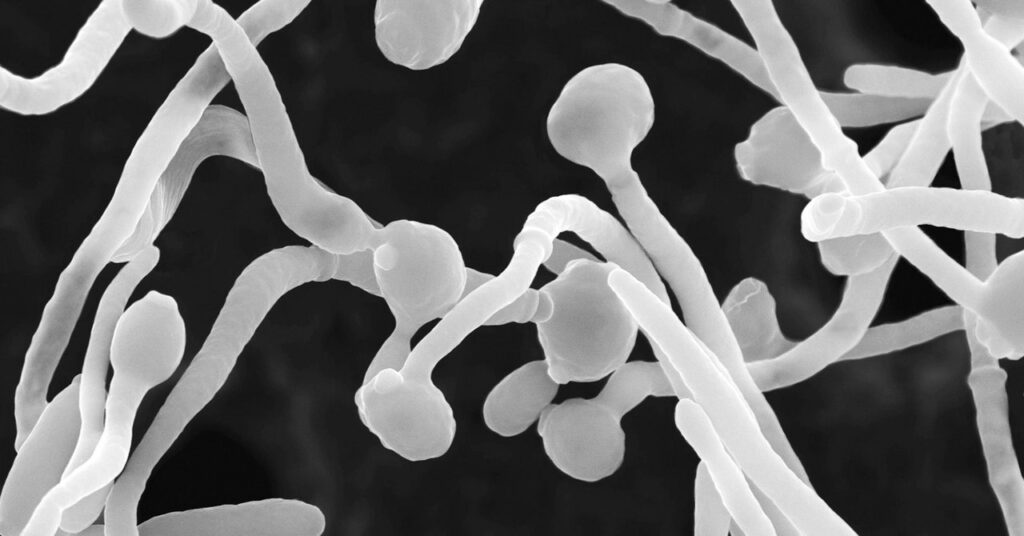

When the team infected mice candida albicans After examining strains taken from severely affected coronavirus patients, researchers found that the mice had increased fungal antibodies and neutrophils. Then, when these infected mice were treated with the common antifungal drug fluconazole, the number of these fungi-induced neutrophils decreased, as did the amount of fungal antibodies. This indicates that the overgrowth of these fungi promotes an increase in the number of neutrophils, and the coronavirus itself initiates the process.

Iliev said neutrophils are an important part of the immune system, but overactivity can lead to prolonged inflammation that is a hallmark of the coronavirus. “The neutrophils will keep coming because they think there’s inflammation and infection,” he added. “They basically start exploding to create structures called neutrophil extracellular traps, which instead of helping you, actually make the disease worse.”

And the effects of this fungal overgrowth did not end even after the patient’s coronavirus infection subsided. By reexamining blood samples from critically ill coronavirus patients and comparing them with blood samples from healthy controls, scientists found that the stem cells that produce these neutrophils are specifically adapted to the fungi they target. I discovered that These stem cells were active long after the initial infection and remained active even after fungal antibody and neutrophil levels declined. This was essentially responsible for preparing the body to respond dramatically to future fungal threats. At this stage, it is not clear whether this will be helpful or problematic for patients. It is quite possible that the patient’s body will overreact to other fungal infections in the future.

There was one final question that puzzled Iliev and his colleagues. So how did fungi living in the gut cause such dramatic changes in the immune system elsewhere, down to the stem cells? To answer that question, scientists looked for signaling molecules known as cytokines. One of these is called IL6, and the researchers noticed that it was elevated in infected mice, along with increases in neutrophils and fungal antibodies. When the researchers blocked IL6, the amount of both neutrophils and fungal antibodies decreased. “Perhaps the intermediaries here are fungus-induced cytokines,” Iliev says, suggesting that these are signs of some kind of communication throughout the body that potentially initiates all these processes.

This complex crosstalk between the gut microbiome and the immune system is an example of how almost everything in the body is intertwined, said Dr. Gastroenterology at Massachusetts General Hospital, who was not involved in the study. says doctor Alessio Fasano. “Gut is not like Las Vegas,” he says. “What happens in your gut doesn’t stay in your gut.”

Fasano envisions this kind of research pointing to a future of more personalized medicine. Measuring elevated levels of fungal antibodies in coronavirus patients could help identify some people who might benefit from taking antifungal drugs such as fluconazole, he says.

But all scientists say it’s unfair to hold a single strain responsible for wreaking havoc on the immune system. The microbiome is in constant flux, so it’s important to reestablish balance after an infection. Throwing tons of antibiotics and antifungals into the problem can create a never-ending game of biological whack-a-mole, where one balance upsets another.

Currently, Iliev and Kusakabe are interested in exploring how fungal overgrowth manifests during long-term coronavirus infections and how immunity is affected. “What are the effects of reprogramming the immune system by fungi and viruses?” Iliev asks. “If I suffer from it, what will happen in the long run?”