newYou can listen to the Fox News article!

In late May 1965, Coca-Cola contacted Peanuts creator Charles Schulz to create a Christmas special cartoon sponsored by the company. Since the television show had only six months to develop, the cartoonist quickly set up a meeting with producer Lee Mendelsohn and program director Bill Melendez.

The three met at Schulz’s home in Sebastopol, California over Memorial Day weekend and together conceived the key elements of “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” which would become the most popular Christmas animated special of all time.

Lee Mendelsohn suggested a Christmas tree as a plot element, and Schulz accepted the idea, saying, “We need a tree like Charlie Brown!” When the producers then suggested inserting a “laugh track” (a recording of the audience laughing), Schulz was offended.

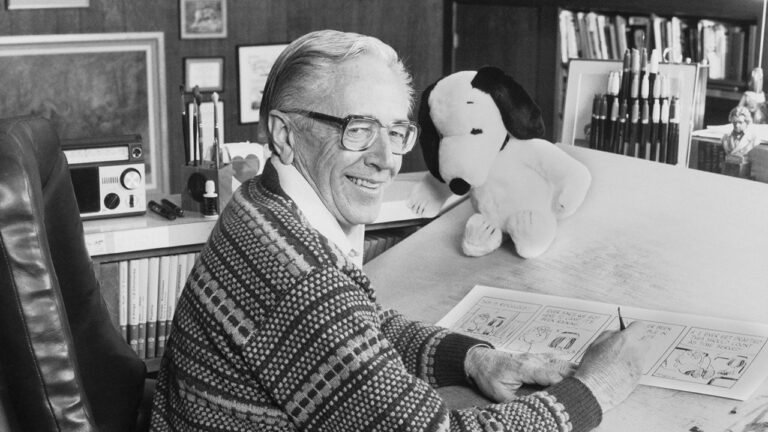

Charles M. Schulz, creator of the comic strip “Peanuts,” draws in his studio next to a Snoopy stuffed toy. (Getty Images)

“No more,” the artist protested, getting up and leaving the room. Melendez relieved the tension by joking, “Well, there won’t be any laughs.” Schultz re-entered the room and the meeting resumed.

I truly understood the meaning of Memorial Day when I became part of this Gold Star family.

The show’s music was also a topic of discussion. Jazz composer Vince Guaraldiproduced a soundtrack for a documentary about Schultz two years ago, but failed to find a buyer.

Schulz also wanted to include a scene in which Schroeder, a piano-playing Peanuts character, plays Beethoven’s music, and the cartoonist insisted that the character’s voice be provided by an actual child, rather than a professional voice actor.

The most contentious issue came when Schulz suggested having Linus recite a passage from the Bible from the Gospel of Luke. “I can’t do that. It’s too religious,” Melendez said. “It doesn’t suit comics.” Lee Mendelson expressed the same concern.

“A Charlie Brown Christmas” first aired on Thursday night, December 9, 1965. (ABC Photo Archive/ABC via Getty Images)

The Bible has never been animated by Warner Bros., Disney, or Hanna-Barbera, and the inclusion of overtly religious material could expose the show to attack by both Christians and non-believers.

American war heroes buried overseas remain defenders of freedom and “continue to serve”

Churchgoers might object, saying it was blasphemous to animate the Bible and have cartoon characters recite its verses; less religious people might be put off by the preachy moralizing. Schulz wasn’t deterred by opposition from his colleagues, who said, “If we don’t do it, who will?”

At one point, as the three relaxed by Schultz’s pool, Schultz, a World War II combat veteran, lamented to Mendelsohn that Memorial Day had lost its original meaning and become merely the start of summer and an opportunity for barbecues.

Now, the cartoonist feared the same thing was happening to Christmas: its true meaning was being lost and replaced by the secular celebration of Santa Claus.

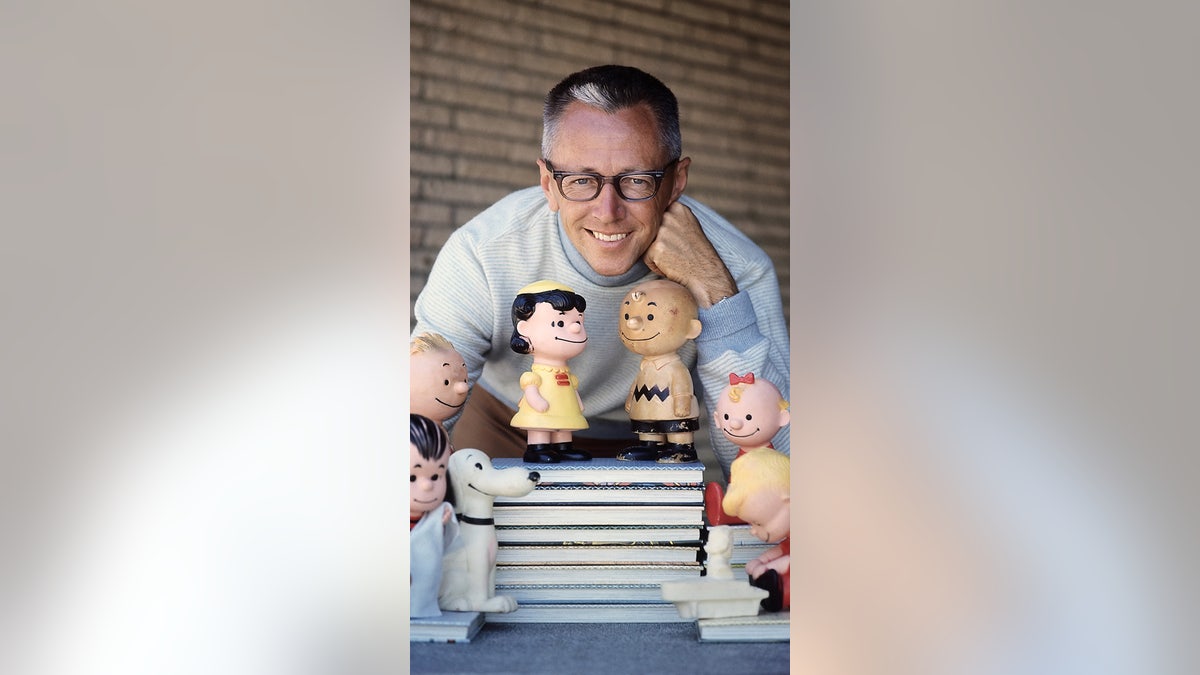

Peanuts reached 60 million people and was published in more than 700 newspapers in the United States and Canada, plus 71 newspapers internationally. (CBS via Getty Images)

In 1965, Charles Schulz was well on his way to becoming the most successful cartoonist of all time: His “Peanuts” comic strips reached 60 million people and appeared in more than 700 newspapers in the U.S. and Canada, plus 71 internationally.

Three things I want my kids to know on our anniversary

His recent book, “Happiness is a Warm Puppy“ It quickly became a New York Times bestseller, licensing opportunities were pouring in, and it had just won two National Cartoonists Society Awards.

But when a visiting reporter asked Schulz what accomplishment he was most proud of, the cartoonist didn’t mention Peanuts, but instead pointed to a three-inch-wide rectangular silver-and-blue enamel bar hanging on his office wall and said, “My Combat Infantryman’s Badge.”

In 1943, at age 19, Schultz had recently lost his mother to cancer and was assigned to Camp Campbell, Kentucky. The combination of bereavement, loneliness and the shock of basic training left the skinny, innocent teenager from St. Paul, Minnesota, traumatized.

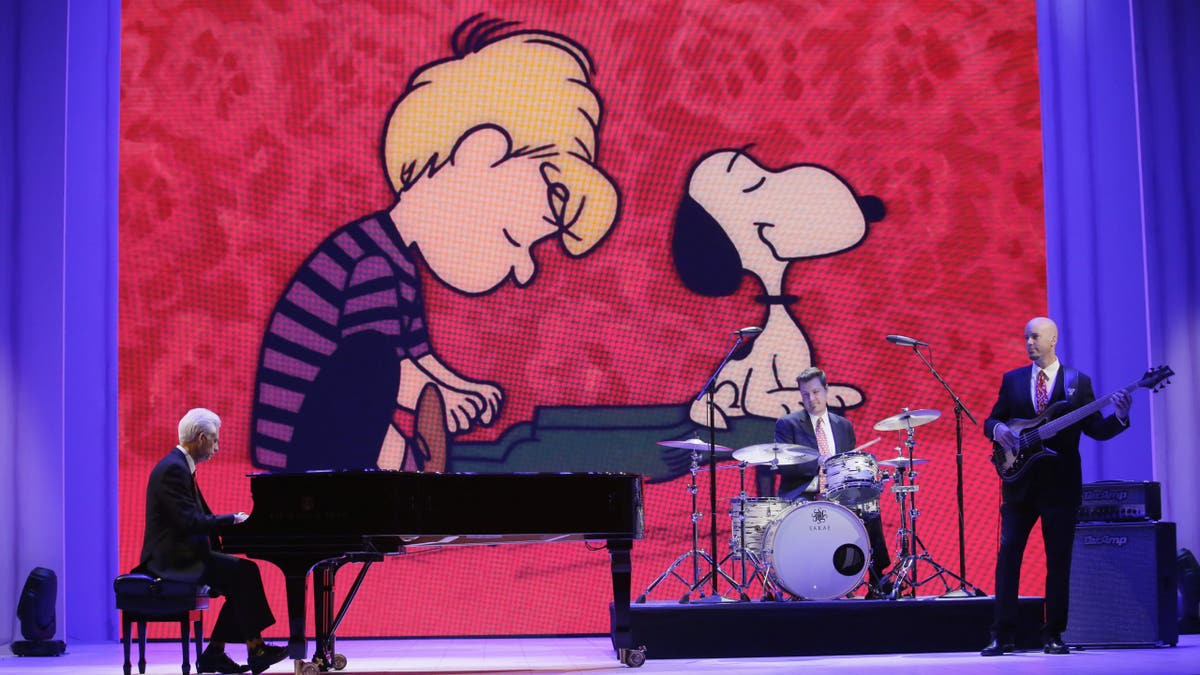

“One Charlie Brown Christmas Turns 50” celebrated the holiday classic’s milestone anniversary in 2015. Schulz insisted on a scene in which Schroeder could play Beethoven’s music. (Nicole Wilder/Disney General Entertainment Content via Getty Images)

But this insecure boy who had just failed his first semester of high school showed competence and intelligence during boot camp, and was promoted to petty officer sergeant and platoon leader a year later when his unit deployed to serve in World War II.

Memorial Day is a reminder that freedom must be continually fought for and defended.

Schurz carried a .50 caliber machine gun as he served in a half-track with the U.S. Army’s 20th Armored Division as they advanced through France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and finally into Germany. In addition to experiencing the horrors of combat, Schurz’s unit also participated in the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp.

Although his wartime experiences left him with indelible emotional scars, they also helped him become a devout Christian who was grateful to God for having survived World War II.

When Schulz’s Christmas special was screened for two CBS vice presidents in December 1965 just a week before it was scheduled to air, network executives were disappointed with the show’s rough animation, dismayed by its jazzy musical score, and uneasy with its overt religiosity.

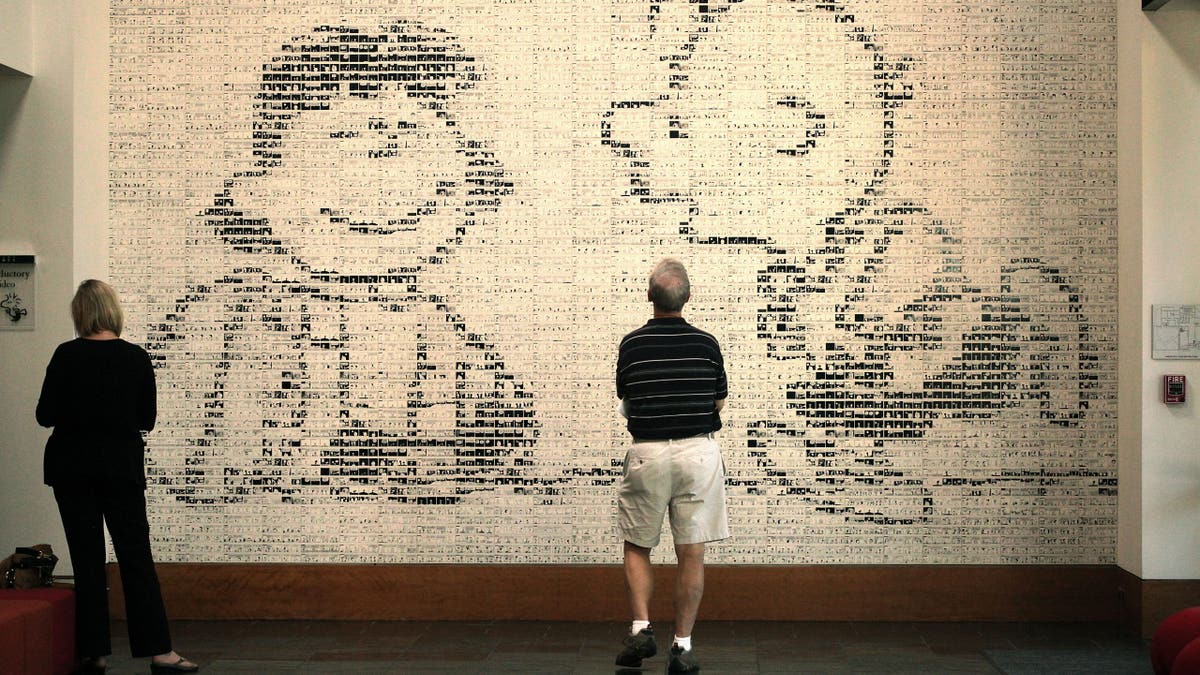

A Peanuts tile mural by Japanese artist Otani Yoshiteru covers the south wall of the Great Hall at the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California on September 22, 2014. The tile mural is made up of 3,588 Peanuts comic strip images printed on individual 2-inch by 8-inch ceramic tiles. (Liz Hafalia/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

The network was convinced that the show would be a ratings flop and ultimately gave up on it, and CBS executives bluntly told Mendelsohn that the network would never buy another special from him or Schulz again.

Click here to read more FOX News Opinion

“A Charlie Brown Christmas” aired on the evening of Thursday, December 9, 1965. It was watched by almost half of America’s television audience, and audience reaction was overwhelmingly positive.

Schulz’s insistence on a religious scene at the show’s climax struck a chord with viewers and appears to have transformed the show from amateur flop to enduring success. (The Bible reading is delivered by the blanket-clutching character Linus, and ends with the words “Peace on earth, good will among men,” which must have special meaning for combat veterans.)

A Charlie Brown Christmas won an Emmy and a Peabody Award and became America’s most popular Christmas animated special.

Producer Lee Mendelsohn suggested a Christmas tree as a story element, and Charles Schulz embraced the idea, saying, “We need a tree like Charlie Brown!” (Walt Disney Television via Getty Images)

Click here to get the FOX News app

Schulz succumbed to colon cancer in 2000, at age 77, and died on the day his final comic strip was published. His simple gravestone doesn’t mention that he was the creator of “Peanuts,” the billion-dollar box office hit, but it does acknowledge the cartoonist’s proudest role in life. Following his name “CHARLES M. SCHULTZ” and above his date of birth, the bronze gravestone is inscribed in capital letters with the words:

U.S. Army Sergeant

Second World War

To read more articles by Michael Keane click here