Dr. Kasgeby uses the Nobel Prize-winning technology Chrispr to modify a patient’s cells to produce healthy hemoglobin instead. The Crispr system has two parts. A protein that cuts genetic material and a guide molecule that tells where in the genome to make the cut.

To do this, a patient’s stem cells are harvested from their bone marrow and edited in a lab. Scientists make single cuts in different genes called . BCL11A, turns on the production of the fetal type of hemoglobin, which normally stops shortly after birth. This fetal version compensates for abnormal adult hemoglobin. The edited cells are injected into the patient’s bloodstream.

A total of 45 patients received Kasugevy in clinical trials. Of the 31 patients followed for two years, 29 remained pain-free for at least a year after receiving a single dose of the self-edited cells.

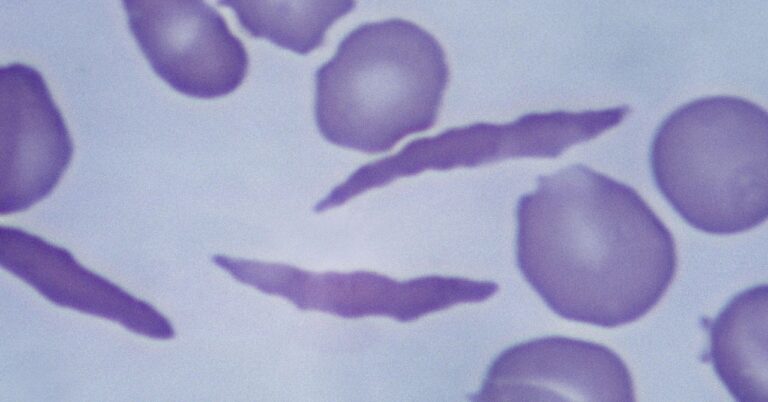

Until now, the only treatment for sickle cell was a stem cell transplant from a related donor, but this option is only available to a small number of people. Transplants can also carry life-threatening risks and are not always effective.

The first civilian patient to receive Kasgevy probably won’t be treated until early next year. It takes several weeks to collect a patient’s cells, edit them, and go through quality control checks before the cells are ready for injection. “It takes a little longer to treat patients,” Kulkarni said. “But we don’t want to waste our time, and our patients don’t want to waste their time either, because they’ve been waiting for this for a while.”

Today, the FDA also approved a second type of gene therapy for sickle cell, Lifgenia. Rather than using Crispr to cut the genome, this therapy adds therapeutic genes to cells so they can produce healthy hemoglobin. Manufactured by Bluebird Bio in Somerville, Massachusetts, the process involves modifying a patient’s cells outside the body. In a two-year study, pain episodes resolved in 28 of 32 patients between 6 and 18 months after treatment with Rifgenia.

The FDA issued a black box warning for Rifgenia indicating a serious safety risk after some patients treated with Rifgenia developed blood cancer. The agency says patients who receive this treatment should be monitored for life.

Alexis Thompson, chief of hematology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, says these new gene therapies will be transformative for patients. “Now I can talk to parents about the possibility of curing their child’s sickle cell disease, a conversation that a few years ago I wouldn’t have had the courage to have with my family,” she says.