One of the most distinctive features of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, is its topography: its surface is covered with rivers, lakes, and oceans. Titan is the only body other than Earth with pools of liquid on its surface, but Titan’s frigid climate (average surface temperature is about -296.59 °F) is too cold for liquid water to exist. Instead, Titan’s rivers and seas are filled with a mixture of light hydrocarbons, mainly methane and ethane. A new study suggests that these liquid bodies may host the waves that eroded the shoreline.

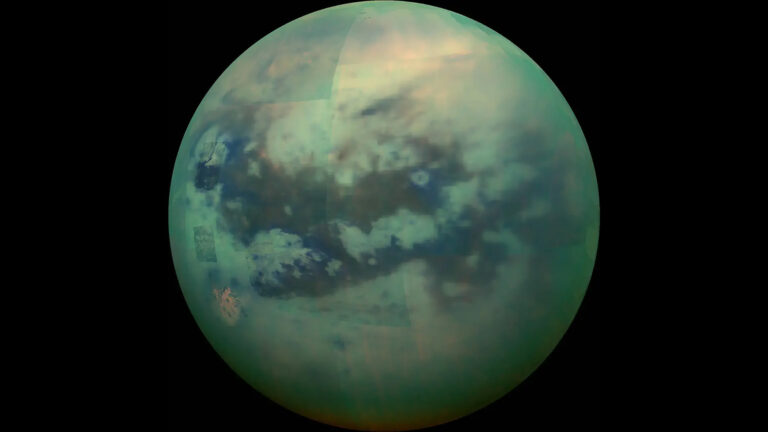

In 2017, the Cassini mission, a joint project between NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian ASI space agency, made several flybys of Titan, collecting a huge amount of data about the Moon and its surface. Most excitingly, the Huygens lander launched by Cassini landed on the Moon’s surface, making Titan the most distant celestial body on which humans have landed.

Despite Huygens’ visit to the moon and decades of studying Titan from Earth, many questions remain about the lunar lakes and seas. One of these is whether waves form on the surface of the lunar lakes and seas. This has long been hypothesized, but actual evidence has proven elusive.

Not only is the distance long, ClosestSaturn is 746 million miles away from Earth, and Titan is Approximately 759,000 miles Directly observing Titan from Saturn poses several other challenges, including its thick atmosphere and characteristic haze, and the fact that its great distance from the Sun means that it receives very little radio wave from the Sun. Only 1% of sunlight This is not the case on Earth, and Titan’s seasons are much longer than Earth’s (about 1 million years each), which could affect wave activity. Seven and a half years on Earth).

new paper On this topic, Scientific advances This month, the authors circumvented these challenges by studying the lunar coastlines and modeling how they were shaped by wave activity.[ed] The team focused on distinct geomorphological features caused by two mechanisms of coastal erosion – wave-induced and uniform erosion – and compared their modeling results with images provided by Cassini.

(a) Cassini SAR image of Ligeia Mare, Titan (NASA).B) Fort Peck Lake (USA) is a reservoir formed by recent flooding of a landscape previously eroded by a river. [Map data: Esri World Imagery, Earthstar Geographics (58)]. (C) Lake Rotoehu, New Zealand, a lake formed by erosion of a flooded river valley by subsequent waves. [Map data: Esri World Imagery, BOPLASS Ltd., Maxar (58)]. (is) Lake Proščanšo in Croatia is a karst lake with a river valley eroded by floodwaters. [Map Data: Esri World Imagery, Maxar, Microsoft (58)]Credit: ROSE V. PALERMO et al.

The results of the experiment suggest that waves are the most likely explanation if the lunar coastline formed by erosion, similar to how water formed coastlines on Earth. However, the authors are careful to make it clear that these results are not conclusive – that is, the results “do not prove that waves form on Titan,” a claim that requires direct observational evidence.

The findings also shed light on what such waves might look like — and, unfortunately for would-be cryo-surfers of the future, Titan’s waves probably won’t be all that impressive: Titan’s slow wind speeds (a product of the moon’s thick nitrogen atmosphere) and the density and viscosity of methane and ethane mean that average waves are only a few inches high.

Despite their agreement Previous researchThe researchers said the results were a surprise, describing the evidence of wave erosion as “somewhat unexpected.” It suggests that even larger waves may be lurking elsewhere on the Moon, perhaps triggered by severe weather generating high winds, or other factors yet to be identified may have also contributed to the formation of the coastline. The paper suggests that this makes “various landforms created by coastal erosion…high priority targets for future Titan rover and lander missions.”