Kherson, Ukraine

CNN

—

Nadejda Chernishova breathes a sigh of relief as she steps off a rubber dinghy, moments after being rescued from her flooded home in Kherson.

“I’m not afraid now, but it was scary in my home,” the 65-year-old retiree said. “You don’t know where the water is going, and it was coming from all sides.”

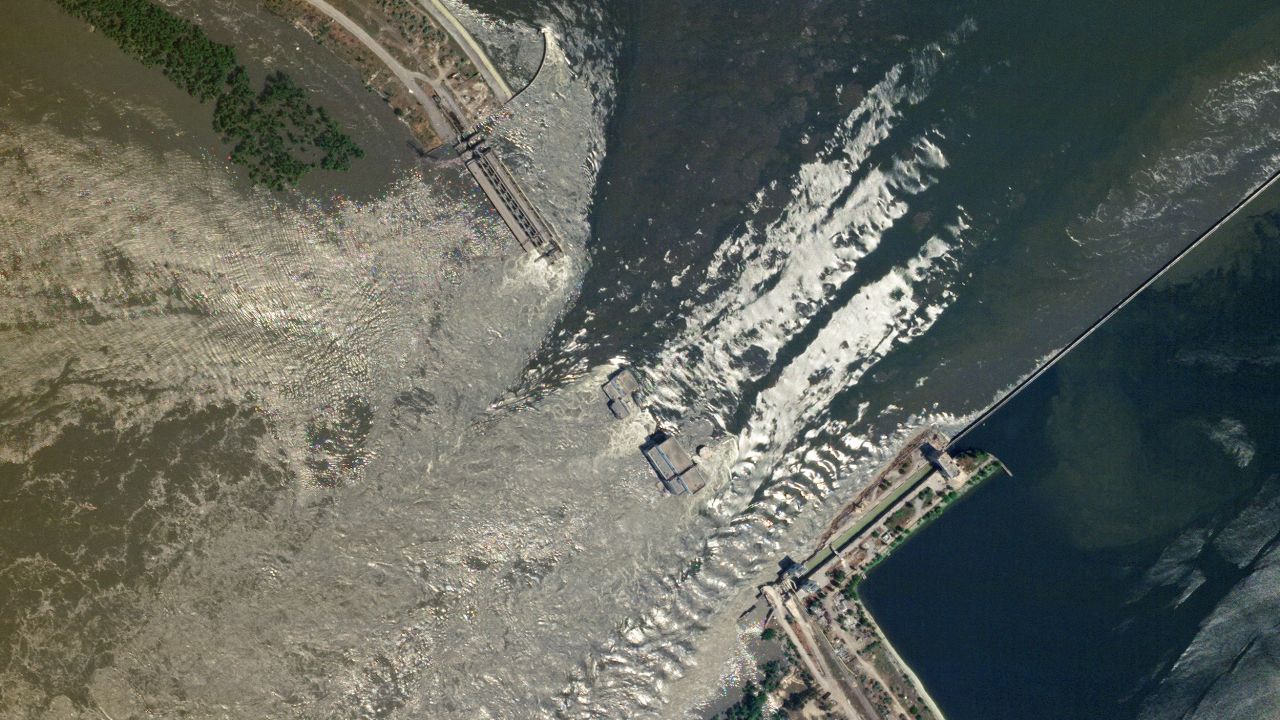

Her house in one of the lower lying districts of Kherson was flooded after the Nova Kakhovka dam, 58 kilometers (36 miles) up the Dnipro river in Russian-occupied Ukraine, was destroyed earlier on Tuesday.

“[The water] went up in an instant,” she added. “In the morning there was nothing.”

Chernishova left most of her small world behind, bringing only what she was able to muster: two suitcases and her most prized possession.

“This is my cat Sonechka, a beauty,” she said, lifting the lid of a small her pet carrier and revealing a frightened animal. “She is scared, she is a domestic cat who has never been outside.”

Chernishova is one of hundreds being evacuated by Ukrainian authorities in Kherson, where the water has spread across several blocks and into the center of the city, cutting off some areas entirely.

“Civilians are being evacuated from the Karobel district. More than 1,200 people have already been evacuated from this area [on Tuesday],” the head of Kherson region military administration, Oleksandr Prokudin told CNN at the scene.

Prokudin, who has been overseeing rescue efforts in towns and cities downstream from Nova Kakhovka, said the operation has become more difficult with time as flood waters continue to rise.

“If in the morning we could do it with cars, then with trucks, now we see that big cars can no longer pass,” he explained. “The water has risen so much that we are now using boats. About eight boats of various types are currently working to evacuate people from the area.”

CNN witnessed the speed at which the waters kept rising, with the water penetrating one block into the city in less than an hour. The flow of water visibly increasing to the naked eye.

In a frontline city like Kherson — where the shelling is constant — the rising water brings an added danger.

“This is both a water element and a mine hazard, because mines float here and this area is constantly under fire,” Prokudin said. Artillery salvos could be heard intermittently, but search and rescue operations carried on, with soldiers and first responders unfazed by the constant thuds.

“We will work around the clock, rescuers will not rest. We’ll change shifts and will pull people out if necessary,” he added.

The large presence of soldiers and first responders contrasts with the very few number of Kherson residents out on the streets. Many fled when Russia first invaded and officials say most still haven’t returned. Those who remain in the city know to take shelter in the afternoon, when Russian artillery fire often picks up.

“It is always very dangerous here. This checkpoint is usually under shelling,” Produkin said. “You see a crowd of people and I think the hit will happen soon.”

Kyiv and Moscow have traded accusations over the destruction of the dam but neither side has provided concrete proof that the other is culpable. But while responsibility for the incident remains as murky as the debris-filled waters now flowing down the Dnipro, its impact is much clearer.

Before the dam collapsed, a potential Ukrainian offensive across the Dnipro to the Russian-held side of the river was unlikely due to difficulty of crossing the river. That seems almost impossible now. Both sides have been severely impacted by the collapse — even more so on the Russian side — leaving the terrain in very difficult condition.

And as she packs her belongings into a car, Chernishova is perfectly clear on who she blames – even if Russia denies it.

The Russians “flooded us,” she said. “Everything is drowning.”