This article was first featured on conversation.

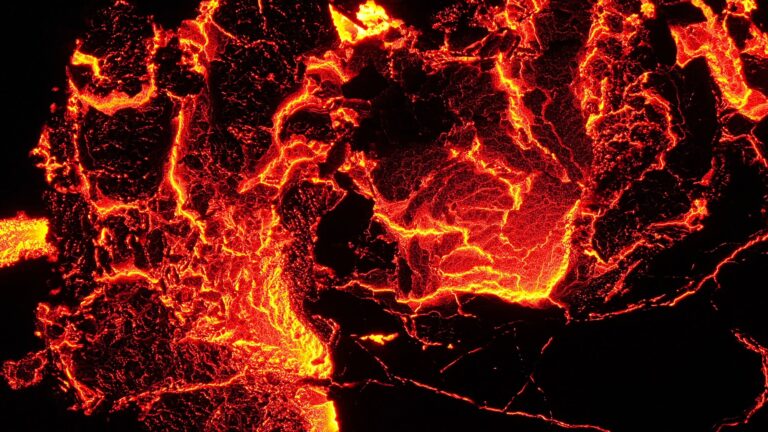

On January 14, 2024, a fountain of lava erupted from the Sundunukur volcanic system in southwestern Iceland. Watched all over the world via webcams and social mediaThe lava flow blocked roads and bubbled through new fissures as it entered the outskirts of the coastal town of Grindavik, burning at least three homes in its path.

Nearby, construction vehicles had been working for several weeks. Build a large earthen dam or dog run It was necessary to retreat to divert the flow of lava.

Humans have used a variety of methods to stop lava, including cooling the lava with seawater and freezing it in place, using explosives to cut off the lava supply, and building earthen barriers. I’ve been trying.

It is too early to tell whether the Icelandic earthworks will be successful in saving the town of Grindavik. Approximately 3,500 residentsand nearby geothermal power plant.as volcanologist, I am following these methods. The most successful attempts to stop or reroute lava have involved detours like those in Iceland.

Why it’s difficult to stop lava

The lava is dull viscous liquid This works similar to tar. Because it is influenced by gravity, it flows downwards, like any other fluid, along the steepest path of descent.

Depending on the temperature of the molten rock, Well over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius), and there is little to prevent it.

Frozen lava remains

In 1973, Icelanders The most famous “lava freezing” experiment. They used water hoses from a fleet of small boats and fishing vessels to protect the small island community of Heimaey from the lava of the Eldfell volcano.

The lava flow threatened to close a port important to the region’s fishing industry and its lifeline to mainland Iceland. Although the eruption ended before the success of the strategy could be properly assessed, the port survived.

Fight lava using explosives

used by Hawaiians Explosives dropped from planes in 1935 and 1942 The effort was to stop a flow of lava from Mauna Loa that was threatening the town of Hilo on the Big Island.

The idea was to destroy the channels or lava tubes within the volcano that feed lava to the surface. Neither attempt was successful. The explosion created a new channel, but the newly formed lava quickly flows out. Returned to the original lava flow path.

Lava barriers and detours

Most recent efforts focus instead on the third strategy. It is the construction of dams and trenches with the purpose of redirecting the lava flow towards another steepest descent path, another “lava flow”. Concepts similar to watersheds But where lava would naturally flow.

Results are mixed, but redirection can be successful if the lava flow can be clearly diverted into a clear area where it should flow naturally, without threatening another community in the process.

However, many attempts to divert the lava have failed.Barrier built in Italy Stopping the lava flow of Mount Etna Although the flow slowed in 1992; Lava eventually got over each.

Iceland’s transformation efforts

Icelandic authorities evacuate residents of Grindavik in November 2023 After the earthquake swarm It showed that the nearby volcanic system was reactivating.

Shortly thereafter, construction began on important infrastructure in the town and nearby, in particular the protective wall for the Svartsengi geothermal power plant. Construction had to be halted in mid-December. first volcanic eruption It occurred about four miles northeast of Grindavik, but work resumed in January. Work was still underway when the magma reached the surface again on January 14th.

Diverting lava in the area is difficult, partly because the land around Grindavik is relatively flat. This makes it difficult to identify clear alternative paths of steepest descent to redirect the lava.

This was announced by Icelandic officials. On January 15, most of the lava from the main fissure began flowing along the outside of the barrier, but new crack It also opened within its boundaries, sending lava into nearby areas. Unfortunately, that means Grindavik is still in danger.

Disclosure: Loÿc Vanderkluysen receives funding from the National Science Foundation.