The U.S. Department of Agriculture posted an unpublished version this week. Genetic analysis of the spread and spread of avian influenza to U.S. dairy cowsprovides the most complete information yet about the data collected by state and federal investigators in this unexpected and alarming outbreak and what it means.

The preprint analysis reveals surprising unknowns about when the outbreak actually began, how many infections are being missed, the only human infection associated with the outbreak, and how widespread the virus is in cattle. It provides some key insights into the outbreak, including whether it continues to evolve. . This information is critical because influenza experts are concerned that this outbreak heightens the ever-present risk that this insidious influenza virus will evolve to spread among humans and cause a pandemic. be.

But that information wasn’t easy to come by. Since March 25, when the USDA first confirmed that a U.S. dairy herd was infected with the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus, the USDA has faced international criticism for not sharing data quickly or completely. are collecting. On April 21, authorities dumped more than 200 genetic sequences into public databases following pressure from outside experts. However, many of these sequences lack descriptive metadata, which typically includes basic and important information such as when and where the virus sample was collected. Independent analysis is frustratingly limited because outside experts do not have critical information. Therefore, the new USDA analysis (which likely includes that data) provides the best possible glimpse into the complete picture of the outbreak.

undetected spread

One big takeaway: USDA researchers believe the spread of avian influenza from wild birds to cattle began late last year, possibly in December. Therefore, the virus likely circulated undetected in dairy cows for about four months before the U.S. Department of Agriculture confirmed the infection in the Texas herd on March 25.

The conclusion of this timeline is roughly consistent with: Previously collected by external experts From limited publicly available data. So while this may not be surprising for people post-infection, it is concerning. Spreads that can go undetected for months have affected the country’s ability to identify and quickly respond to new outbreaks, and the public health response’s impact in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This raises serious concerns about whether we are moving past the failures seen at this stage.

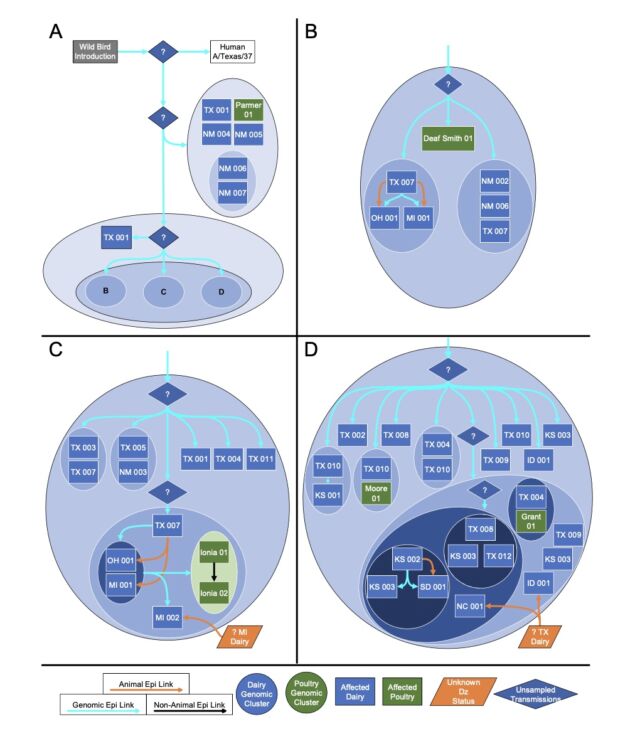

But another big finding from the preprint is how many gaps still exist in our current understanding of the epidemic. To date, the Department of Agriculture has identified 36 herds in nine states infected with H5N1. The good news from genetic analysis is that the USDA can draw a line connecting most of them. USDA researchers believe that “direct movement of cattle based on production practices” may have caused H5N1 to spread from the Texas Panhandle region, where the initial spread is believed to have occurred, to nine other states, including states as far away as North Carolina. reported that it seems to be explaining how he jumped to a certain place. Michigan and Idaho.

The putative transmission route for HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b genotype B3.13 is supported by epidemiological associations, animal movements, and genomic analyses. [/ars_img]The bad news is that there are no solid lines connecting the herd. Gaps exist where genetic data suggests that unidentified infections occurred, perhaps in cows that were not sampled, or in other animals entirely. Genetic data clearly shows that once this avian influenza strain (H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4 genotype B3.13) jumps into cattle, it can easily spread to other mammals. Genetic data shows that the virus has moved from cows to other animals multiple times. Five cases occurred when the virus was transmitted from cattle to poultry, once from cattle to raccoons, twice when the virus was transferred from cattle to domestic cats, and three times when the virus was transmitted to domestic cats. What leaked from the cows returned to the wild birds.

“Existing analyzes suggest that this genotype may be sampled because of missing data and lack of surveillance may obscure inferred transmission using phylogenetic methods.” “We cannot rule out the possibility that the virus is circulating in unprotected locations or hosts,” USDA researchers said in a preprint.