Akira Iwase et al., 2024/Tokyo Metropolitan University

When Japanese scientists wanted to learn more about how polished stone tools dating back to the Upper Upper Paleolithic were used, they built replicas of hatchets, axes, and chisels themselves, and used these tools. I decided to use it to perform a typical task. For that era. According to one report, the resulting damage and wear allowed new criteria to be developed for determining the functionality of ancient tools. recent papers Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. If such traces were indeed found on genuine Stone Age tools, it would provide evidence that humans were working with wood and using grinding techniques much earlier than previously believed. Probably.

The development of tools and techniques for woodworking purposes began simply with the manufacture of crude tools such as spears and throwing sticks that were common in the early Stone Age. Later artifacts, dating back to the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, became more sophisticated as people learned to use polished stone tools to make canoes, prows, wells, and build houses. Researchers typically date the appearance of these stone tools to about 10,000 years ago. However, archaeologists have discovered numerous stone artifacts with ground edges dating back 60,000 to 30,000 years. However, it is unclear how these tools were used.

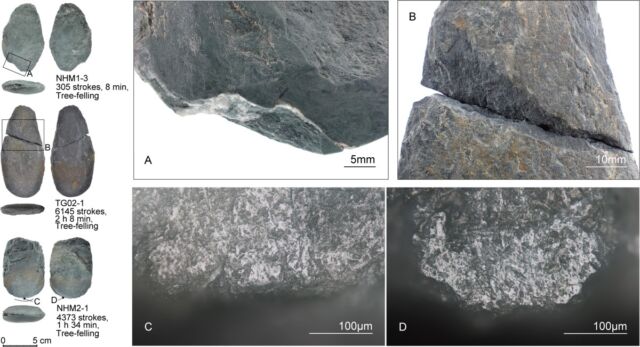

So Akira Iwase and his colleagues at Tokyo Metropolitan University created their own axe and ax replicas from three raw materials that were common to the region from 38,000 to 30,000 years ago: semi-nephrite rock, hornfels rock, and tuff. did. They used stone hammers and anvils to create various long oval shapes and polished the edges with coarse-grained sandstone or medium-grained tuff. He had three types of replica tools. One is the adze type with the working blade oriented at right angles to the long axis of the bent handle. Ax type with a working blade parallel to the long axis of the curved handle. There is a chisel-type one with a stone tool placed on the end of a straight handle.

Akira Iwase et al., 2024/Tokyo Metropolitan University

Now it’s time to test the replica tool through 10 different usage experiments. For example, the authors used an axe-like tool to cut down cedar and maple trees in north-central Honshu, as well as forests near Tokyo Metropolitan University. Ax-shaped and chisel-shaped tools were used to make dugout canoes and wooden spears, and ax-shaped and chisel-shaped tools were used to scrape the bark of fig and pine trees. They used ax-shaped and chisel-shaped tools to scrape the meat and fat from the fresh and dried skins of deer and boars. Finally, they used a hatchet-shaped tool to disarticulate the femur and tibia of the deer’s hind legs.

The team also conducted several non-tool experiments to identify accidental fractures unrelated to tool-use functionality. For example, flakes or blades can break in half during flint knapping. For example, carrying tools in a small leather bag can cause microscopic delamination. Also, stepping on tools left on the ground can cause the cutting edge to become deformed. All these scenarios were tested. All tools used in both used and unused experiments were then inspected for both macroscopic and microscopic evidence of damage or wear.

Tokyo Metropolitan University

As a result, we were able to identify nine types of macroscopic cracks. Some of them were only seen when making shocking movements, especially when cutting down trees. There were also obvious microscopic marks resulting from friction between the wood and stone edges. Cutting through horns and bones causes significant damage to the ends of tools such as axes, resulting in long and/or wide bending fractures. The tools used to disarticulate the limb caused fairly large flexion fractures and small avulsion marks, but only 9 of his 21 scraping tools, despite hundreds of repeated strokes, It showed visible signs of wear.

The authors concluded that examining macroscopic fracture patterns alone is insufficient to determine whether a particular stone tool was used for impact. Also, the microabrasiveness produced by polishing itself is not a clear indicator, as the scraping action produces similar microabrasiveness. However, combining the two yielded a more reliable conclusion about which tools were used for percussively felling trees compared to other uses such as cutting bones.

DOI: Journal of Archaeological Sciences, 2024. 10.1016/j.jas.2023.105891 (About DOI).