If you make a hole in the ovary of a wasp called microprotrusion destroyer, the virus gushes in abundance, glistening like iridescent blue toothpaste. “It’s very beautiful, and it’s amazing that so many viruses are being made there,” said Galen Burke, an entomologist at the University of Georgia.

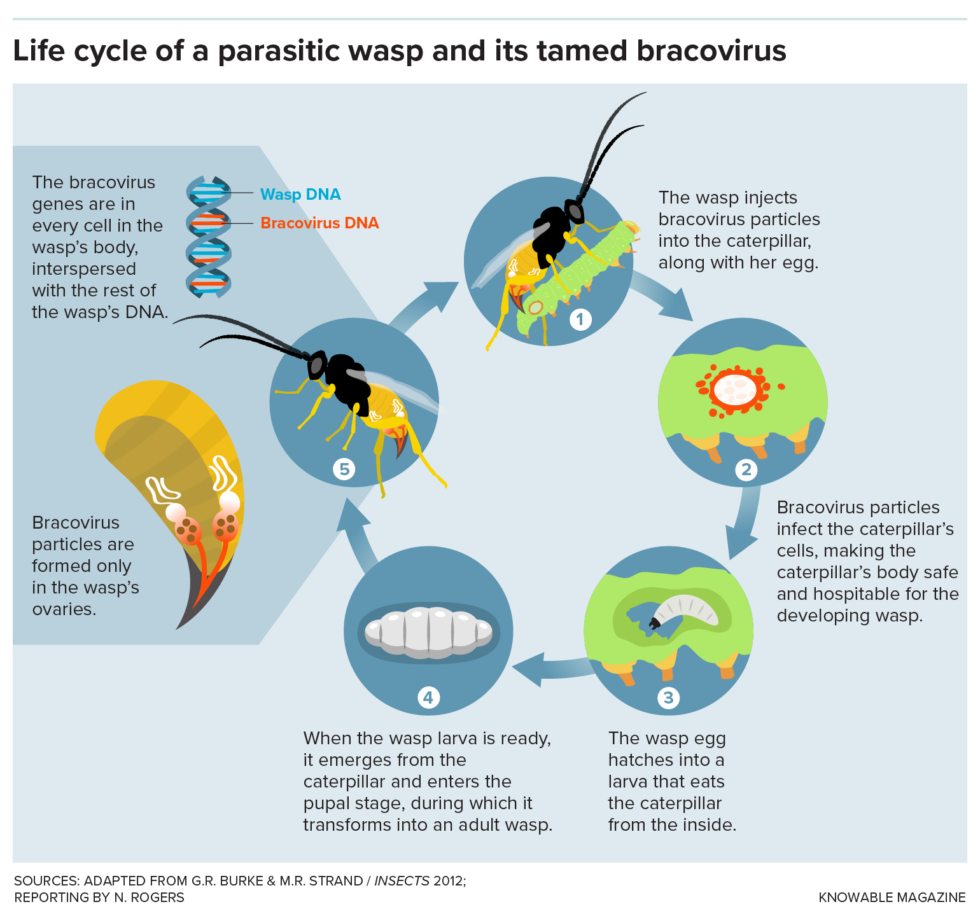

M.Demolition companyis a parasite that lays eggs inside the caterpillar, and the particles inside the ovary are “domesticated” viruses that persist harmlessly inside the wasp and are tailored to serve a purpose. The virus particles are injected into the caterpillar through the wasp’s stinger, along with the wasp’s own eggs. The virus then delivers its contents into the caterpillar’s cells, gene It’s different from normal viruses. These genes suppress the caterpillar’s immune system and control its development, turning the caterpillar into a harmless nursery for young bees.

In the insect world, there are many species of parasitic wasps that spend their young lives eating other insects alive. And although scientists don’t fully understand why, they have repeatedly co-opted wild disease-causing viruses, domesticated them, and turned them into biological weapons. Six cases have already been described, and new research suggests more.

By studying viruses at different stages of domestication, researchers today are unraveling how the process unfolds.

Partner in diversification

Typical examples of viruses domesticated by wasps include a group called bracoviruses. derived from a virus that infects the host of a wasp or its caterpillar 100 million years ago. The ancient virus spliced its DNA into the wasp’s genome. Since then, it has become part of the wasp family and has been passed down to new generations.

Over time, wasps diversified into new species, and viruses also diversified. Bracoviruses are currently found in approximately 50,000 species of wasps, including: M.Demolition company. Other livestock viruses are descendants of various wild viruses that entered the wasp genome at different times.

Researchers are debating whether domesticated viruses should even be called viruses at all. “Some say this is definitely still a virus. Others say it’s integrated, so it’s part of the wasp,” said ecologist Marcel Dicke of Wageningen University in the Netherlands. says. Described how domesticated viruses indirectly affect plants and other organisms In a 2020 paper by Annual Review of Entomology.

As the wasp-virus complex evolves, the viral genome becomes scattered within the wasp’s body. DNA. Although some genes are destroyed, the basic set essential for making infectious particles of the original virus is preserved. “All of these parts are in different places in the wasp’s genome. But they can still talk to each other. And they still make products that cooperate with each other to make virus particles. ,” says Michael Strand, an entomologist at the University of Georgia. However, rather than containing a complete viral genome like wild viruses, domesticated virus particles serve as vectors for the wasp’s weapon.

These weapons come in a wide variety. Some are proteins, while others are genes on short segments of DNA. Most bear little resemblance to those found in wasps or viruses, so it’s unclear where they originated. And they are constantly changing, locked in an evolutionary arms race with caterpillar and other host defenses.

In many cases, researchers still don’t understand how the genes and proteins work inside the wasp’s host, or even if they function as weapons. But they did unravel some details.

for example, M.Demolition companyWasps use bracoviruses to transmit a gene called . glc1.8It invades the immune cells of moth larvae.of glc1.8This gene causes infected immune cells to produce mucus, which prevents them from attaching to wasp eggs.other genes are M.Demolition companyBracoviruses cause immune cells to kill themselves, while others prevent caterpillars from suffocating the parasites with their melanin sheaths.