newYou can listen to the Fox News article!

Gender is a choice, and indeed, it is a complicated choice because there are many genders. If a 12-year-old girl believes she is a boy, or “non-binary,” and wants to undergo a life-changing surgery, she may be harmed because adults will encourage her not to make irreversible changes, at least until she is old enough to get a tattoo. Climate change is “the greatest existential threat to the world,” and a good enough reason for young people to live in debilitating fear and decide not to have children. It is racism that yearns for a society that doesn’t care about skin color. The key to making the Army “stronger” and the Secret Service better at dealing with “the evolving threats facing our nation’s leaders” is to put more women on the front lines. New York became “stronger” by giving city contracts priority to companies owned by men who enjoy sex with men as well as women.

These ideas, and many others like them, are absurd. Yet they are so mainstream that they have been adopted as policy or are the basis for policy in many important institutions and even governments. How did this happen?

Conservatives tend to blame universities and the media. It is true that universities in general are incubators of ideas, and these ideas often have their origins in academia. Some media outlets promote these ideas, but others nevertheless point out their absurdity.

Shabbos Kestenbaum, a graduate of Harvard Divinity School, maintains his faith amid anti-Semitism and is “proud to be Jewish.”

In other words, it is too easy to blame academia or the media for the mainstreaming of stupid ideas. We Americans are not victims of academia or the media, we are not victims of anything. Because we are not victims, we get to set the conditions of our culture, our politics, and our society.

Because Joseph was faithful to his faith, he prospered in Egypt under the rule of Pharaoh. File: The Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt. (iStock)

So how did such absurd ideas move beyond the minority to become normative opinion and mainstream public policy? To take an example from my own state, why is New York trying to pass a constitutional amendment that would guarantee children the right to change their gender?

The answers, as well as truths in general, are found in the Torah.

In Genesis 39, Joseph is sold into slavery by his brothers, the only Jew in Egypt. Potiphar’s wife tries to seduce him. He resists, explaining that he “cannot perpetuate this great evil against God.” She frames him for attempted rape, and he is thrown into prison along with the chief butler and the chief baker.

They each have a disturbing dream and tell Joseph that the dream is impossible to interpret. Joseph, who established himself as a master dream interpreter as a teenager in the land of Canaan, basically says, “Test me.” But that’s not how he says it. He says, “Isn’t the interpretation God’s? Tell me, if you will.”

He understood the dream and its interpretation accurately. Two years later, Pharaoh had two disturbing dreams that he could not understand. At that time, the cupbearer, who was again a free man in Pharaoh’s service, suggested that Pharaoh send for a “young Hebrew man” who was languishing in prison. The young Hebrew man, Joseph, was defined by the pagan cupbearer by his love for God.

Pharaoh summoned Joseph and told him that he had a dream that “no man could interpret,” but that “it was said to me that you are able to understand and interpret the dream.”

Joseph, the usual “Hebrew youth,” quickly responded, “That is not mine to know. It is God who answers regarding Pharaoh’s welfare.”

Joseph again proudly speaks of God. He provides a brilliant interpretation of Pharaoh’s dream and a solution to the problem it revealed.

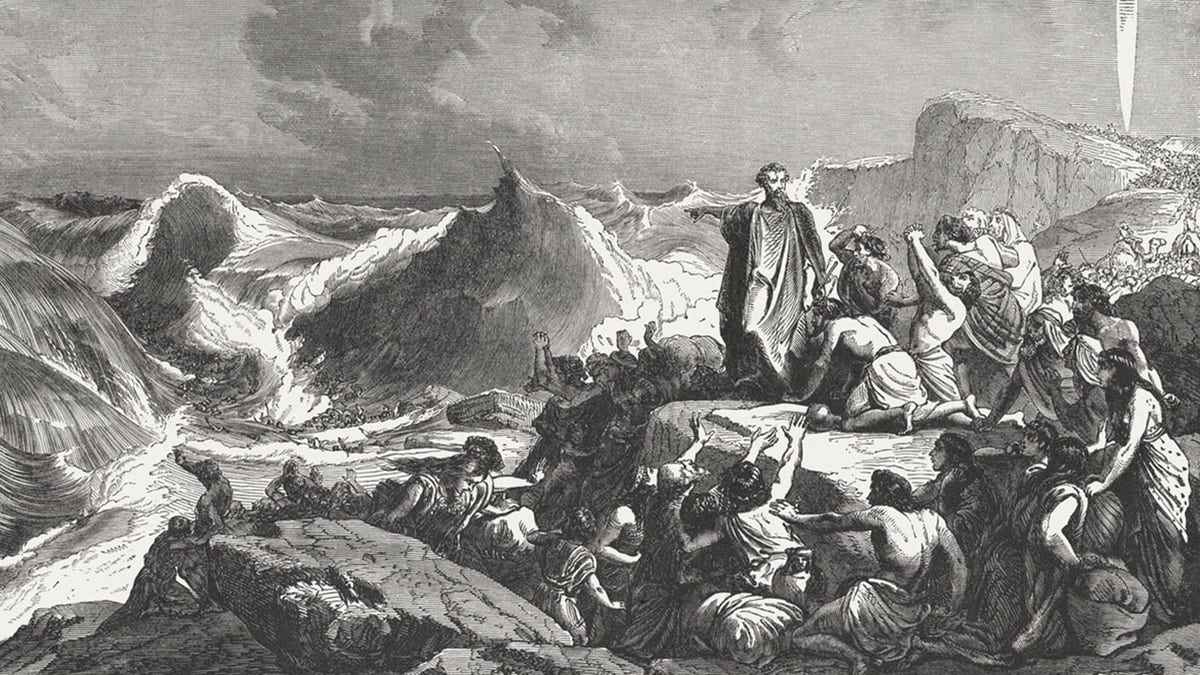

Moses was denied entry into the Promised Land because he did not publicly practice God’s truth. Here we see Moses leading the Jewish people out of Egyptian slavery. (iStock)

Pharaoh said to his servants, “Can we find a man like him, a man in whom the spirit of God was? Pharaoh was apparently convinced of the greatness (and perhaps uniqueness) of God and was equally impressed with the young man who spoke of God everywhere. Pharaoh gave Joseph authority over the entire kingdom.

This utter drama — Joseph going from forgotten prisoner in Pharaoh’s dungeon to prime minister of Egypt in just one hour — leaves the reader asking, “What on earth happened?” Joseph always speaks of the truth (God), even though he is the only Jew in Egypt. He doesn’t care what the local polytheists think. He doesn’t calculate whether his emphasis on his devotion to God will help or hurt his career. Joseph doesn’t consider that Pharaoh, with his many gods, would be offended by Joseph’s emphasis that there is one God in charge of all things.

Joseph simply speaks God’s truth clearly and consistently, and the Torah helps us to see that such truth-telling ultimately results in good for God, Joseph, Pharaoh, and the world. Joseph’s administrative genius ensures that people are fed in the midst of a devastating global famine.

The reader may wonder: what is the significance of Joseph’s habit of speaking God’s truth in general? Is it about himself and Pharaoh, or about all of us, whoever and wherever he is, and always speaking the truth?

Ancient papyrus scroll with Hebrew text (iStock)

Fast forward to the book of Numbers. Moses has been leading the Jews through the desert for a long time. It has been a journey that has been satisfying, wonderful, difficult, and downright crazy at times. In Numbers 20, we are at the crazy stage. The people, after years of God’s care and protection, are in danger of rebelling again because in a short time and without enough food.

Moses, who had just lost his beloved sister Miriam and had no time to grieve or mourn, was commanded by God to speak to the rock that would produce water for the people. But Moses struck the rock, and God forbade him from leading his people to the Promised Land, which was his life’s goal.

Click here to read more FOX News Opinion

The discrepancy between sin and punishment — Moses striking a rock instead of speaking to it, and being denied entry to the land after decades of faithful service and brilliant leadership — has intrigued Jewish Bible commentators for millennia. But the reason for God’s punishment is likely found in the text. God tells Moses he cannot lead his people into the land because “you have not sanctified me in the eyes of the children of Israel.” Moses was not denied entry to the land because he did not act in truth; he was denied entry because he did not act publicly.

Why does the Torah, through the stories of Joseph and Moses, insist that we speak the truth publicly? The answer is revealed in modern social science. In 1993, Princeton University professors Deborah Prentiss and Dale Miller asked students two questions. First, do you think your classmates drink too much? Most students answered “yes.” Second, do you think other students think your classmates drink too much? Most students answered “no.”

He understood the dream and its interpretation accurately. Two years later, Pharaoh had two disturbing dreams that he could not understand. At that time, the cupbearer, who was again a free man in Pharaoh’s service, suggested that Pharaoh send for a “young Hebrew man” who was languishing in prison. The young Hebrew man, Joseph, was defined by the pagan cupbearer by his love for God.

From this contradiction, they identified the concept of “pluralistic ignorance” – the phenomenon in which people mistakenly believe that their opinions are not widely held. The Princeton experiment shows how pluralistic ignorance persists even on widely debated subjects, such as drinking on college campuses. The cure for pluralistic ignorance is simple: if people expressed their beliefs clearly and confidently, pluralistic ignorance would cease to exist, because everyone would know everyone else’s position. Yet pluralistic ignorance still persists.

So how did we get to a point where the idea that men have no biological advantage in sports has become a serious idea that has been debated in a Senate hearing? Here’s a fundamental question each of us can ask ourselves, rather than others:

Click here to get the FOX News app

Were we like Joseph, who spoke the truth under all circumstances? Did we sanctify the truth by speaking it in public, as God commands us in Numbers 20? Or did we shrink from the truth because we worried about being socially ostracized, worried about being bad-mouthed, or fearing that doing so would cost us some social benefit (a promotion, an invitation, a spot in school for our children)? The answers to these questions are individual and varied. But we all know the general answer: We have all been in rooms where Joseph was not present, where people quietly agreed to believe an obvious truth, or where others (often people in authority) reported that they “really knew” the truth but were not speaking it.

Joseph’s promotion and his insistence that God “be made holy in the eyes of the children of Israel” teaches us that such rejection is not harmless. And for good reason. Ideas are the foundation on which everything else rests and operates—personal decisions, public policies, cultural norms, and societal rules. When true ideas are rejected, a vacuum is created that is so desperate to be filled that any idea, even absurd ones, is embraced. Through Joseph in Genesis and Moses in Numbers, the Torah teaches us how to keep our foundations safe and strong: by speaking the truth publicly and with confidence.

For more information on Mark Gershon click here