I changed my mind a long time ago, but anyone swayed by Potter’s antipathy towards domesticity and agricultural idylls should visit the Morgan Library. There are smart and convincing exhibits.Beatrix Potter: drawn to nature” depicts her as a multifaceted talent. In this book, published in 1902,Peter Rabbit’s story‘But this work explores her life from her privileged childhood in the London middle class to her later years as a farmer, conservationist and defender of the English Lake District, the landscape she loved most. It also covers larger trajectories.

That larger perspective is a strange combination of fascination and unsentimental menace in her work, the idea that worlds exist that are not entirely continuous with ours, and that when they come into contact they are subject to friction and conflict. It helps clarify the feeling of being able to do something. That friction can be potentially deadly, whether it’s a rabbit caught in a garden net or the temptation of fate with a farmer’s gun (at the cost of whiskers and tails). Sometimes it’s comedic, but it’s often hard to tell where the comedy stops and the potential tragedy begins.

Consider the advice given to Peter and his brothers at the beginning of “Peter Rabbit” not to go to Mr. McGregor’s garden. “Your father had an accident there. He was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor.” He could see Mr. McGregor holding it and poised over a pie the size of a piping hot rabbit.

The understatement, “My father had an accident,” suggests that this is a comic moment, as does the farmer’s skeptical expression and the reference to Shakespeare. But for Rabbit, it’s a dark memory of trauma and loss. The same goes for The Tale of. “Jemima Puddle Duck” (1908), a scene in which a naive and charming young cock is seduced by a cunning fox, seems funny, but is gendered in a way that feels like a setup for rape. .

The menace in Potter’s works feels different from the dark fables common in classic fairy tales. Part of the difference lies in Potter’s drawings, which are no coincidence, nor are they simply illustrations of the text. As the exhibition demonstrates, Potter’s fairy tale illustrations are based on her deep observations of the natural world. Long before inventing Peter Rabbit, in her 1893 personal letter to her former tutor’s five-year-old son, Potter was meticulous in the details of plants, animals, and mushrooms. I paid for it and drew pictures. By the late 1880s, she had developed into a sophisticated amateur mycologist, and in 1897 one of her scientific papers was read at the Linnean Society in London (women were not allowed to present their own research). This was not allowed, so a man read it aloud).

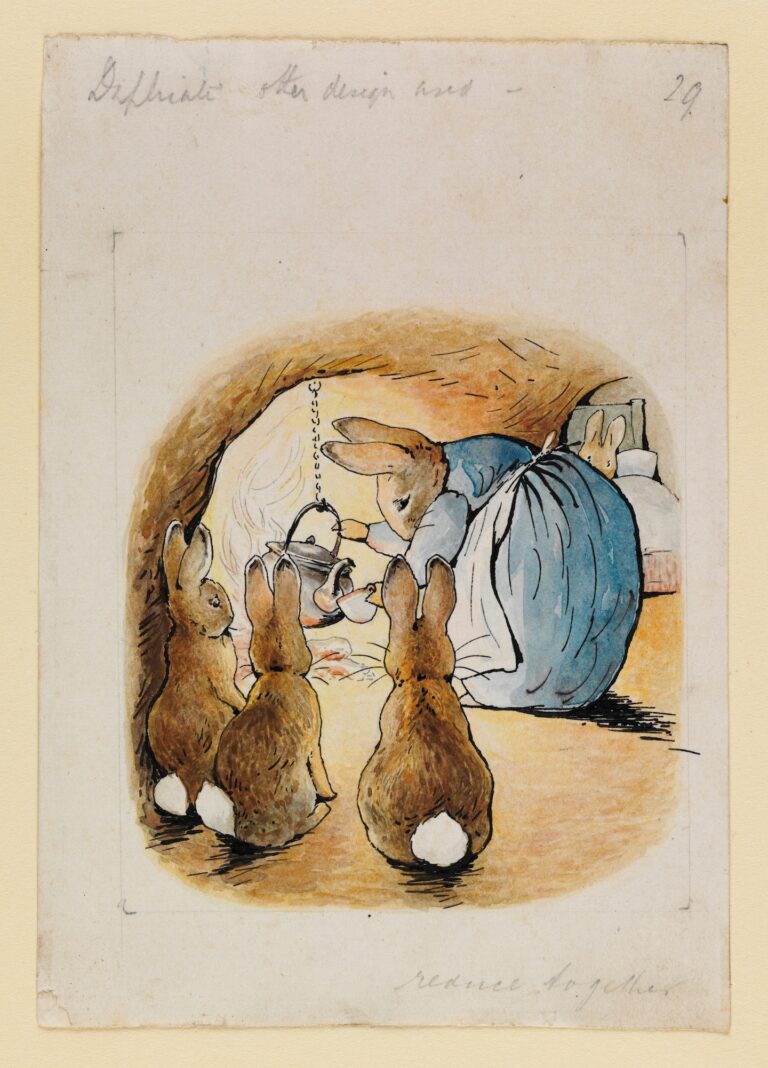

The main difference between the animal drawings she did before starting her career as a writer and the illustrations for children’s books is that she uses a small amount of ink over a watercolor with shadows to draw children from the real world. A clearer outline has been added, as if to clarify the transition to fantasy. . Roughening some sharp edges is akin to adding Victorian moralism to the animal world. Her rabbits, kittens, mice, and squirrels are anthropomorphic, but there’s always a ruthless survival-of-the-fittest mentality in the background, a surreal mix of old-fashioned, cozy English domesticity and Darwinian rigor. It creates a fusion.

Some might say that was the definition of England at the height of the Empire. Polite, courteous, and comfortable for those at the top. It’s cruel to everyone below. If you want to read Potter that way, there are many avenues. Nutkin, a cheeky squirrel, constantly torments the taciturn old owl with riddles and rhymes, but he does not know his place in the hierarchy of nature. His punishment: Not only does he lose his tail, but he also apparently loses the ability to speak. Among the privileges of power is to police our right to be heard and communicate in the language of our choice. The exhibition features original drawings from 1903’s “The Story of Nutkin the Squirrel,” as well as his 1905 letter in which Nutkin begs Old Brown, the owl, to give him back his tail.

And then there’s the privileged life that Potter enjoyed. Her discovery of the natural world came, in part, during a long vacation in the countryside, including a few weeks in the spring cleaning a house in London. The wealth she earned from writing children’s books and selling Potter goods such as board games, dolls and figurines enabled her to buy large tracts of farmland in the Lake District, where she lived in rural areas with wealthy city folk. I did what most people do: create a fantasy. The hotel has a rustic, homely atmosphere, with a mix of rustic furniture, rare antiques and art. She identified herself with the people she found there and joined what William Wordsworth called “a perfect republic of shepherds.” She looked after a vast flock of sheep and imagined her family’s commercial pedigree to be as vigorous and robust as her ewes.

If, like me, you’re intrigued by this caricature of her life and work, how can you bring Potter back enough to enjoy the charm of her palm-sized book?

The revelation for me was roadkill, the small, hairy carcasses of dead animals that are found on the side of almost every highway that passes through fields, forests, and farmland. I have participated in this massacre at least once, and it was a painful experience. You realize the toll and sacrifice your existence takes on a world, a world that never asked to intersect with yours. Humans destroy, destroy and leave nature in ruins just to make dinner by 6pm.

Our only hope for avoiding the pain of this realization is to try to be kinder and better within the small areas we can control. Literary critic Edward Said argued that many of the great novels of the 18th and 19th centuries were symptoms of imperialism, and that Beatrix Potter’s books could extend that discourse to children. . But they are more than that. They enact common sense without regard to larger historical meanings. And not only nature Perhaps it is possible to see so clearly the inevitable pathos of animal life, despite humans’ dissonant position within it.

If, like me, you worry about overthinking children’s books, here’s one final thought. In his second room in the exhibition, the designer created a kind of window seat that mimics the interior of the house where Potter likely lived. When I visited, one of the boys, about 10 or 12 years old, was reading “The Story of the Ginger and the Pickle” (1909). The story is about two predatory animals, a tomcat and a terrier, who run a shop frequented by wild animals. Prey, rabbits, rats. The store owners are drooling and are having a hard time concentrating on their business. “It would be a shame to eat your own guests,” says Pickles, a terrier.

If the boy had a cell phone, he never looked at it.

Beatrix Potter: drawn to nature is on display at the Morgan Library in New York until June 9th. theorgan.org.