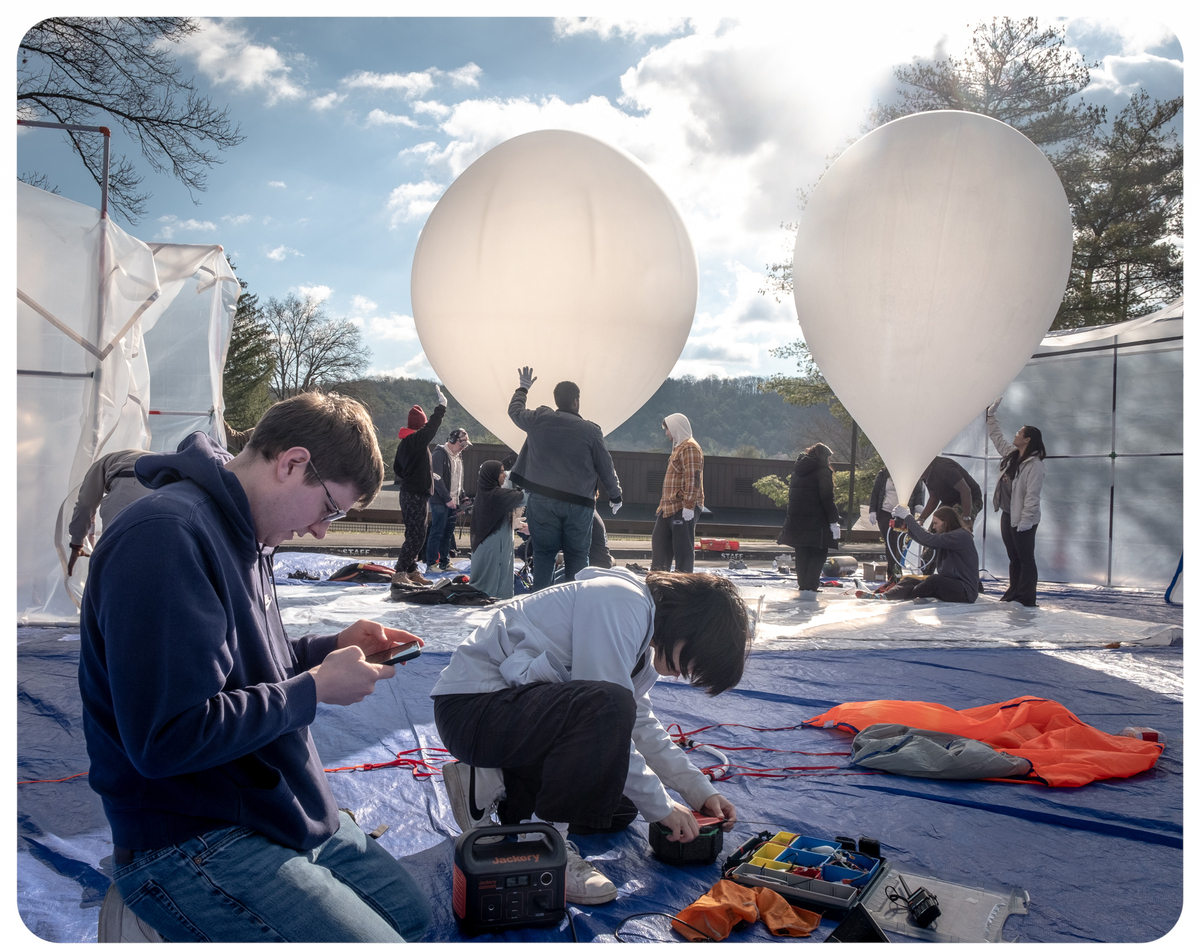

Student volunteers prepare balloons for a morning launch in Cumberland, Maryland. On the day of the solar eclipse, April 8, hundreds of balloons will be launched into the solar eclipse’s orbit to study the atmosphere.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

Student volunteers prepare balloons for a morning launch in Cumberland, Maryland. On the day of the solar eclipse, April 8, hundreds of balloons will be launched into the solar eclipse’s orbit to study the atmosphere.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

CUMBERLAND, Md. — On a chilly March morning, Mary Borden stands in the parking lot of her local community college.

Bowden is a professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Maryland. Nearby, her students hustle around on bright blue tarps, unroll heavy cylinders of compressed gas and tinker with boxes of electronic equipment.

“This is the last, final dress rehearsal,” Borden says, looking around the scene.

A total solar eclipse will sweep across the continental United States early next month. It will start in Texas, travel north through more than a dozen states, then exit the country through Maine and enter Canada.

On the day of the solar eclipse, April 8, dozens of student teams across the country will release hundreds of research balloons. The balloon carries a long, dangling string of scientific instruments to a total path, an area of the Earth’s surface where the sun is completely blocked and the moon is visible.

an effort known as National solar eclipse balloon project, supported by NASA. This is an opportunity to make unique atmospheric measurements that can only be made during a solar eclipse, and for students to learn skills they can one day use to launch satellites and astronauts into orbit. Borden coaches the University of Maryland team, which is made up of about 30 to 40 students.

“This is just a club,” said Daniel Grammer, a junior who will lead the team on eclipse day. “Everyone here is doing it voluntarily because they want to do it.”

floating lab

When deflated, the balloons look like giant party balloons. Once filled with helium, it will begin to take shape. Two white upside-down tears sway silently in the spring air.

Saimah Siddiqui is a senior at the University of Maryland. She hopes her research on balloons will eventually lead to a career as an air traffic controller.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

Saimah Siddiqui is a senior at the University of Maryland. She hopes her research on balloons will eventually lead to a career as an air traffic controller.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

Saimah Siddiqui is a senior and one of the “inflation leaders” responsible for filling the balloons.

“Where am I?” she asked as another student bent over the helium tank’s regulator. Siddiqui seems confident, and with good reason.

“I’ve done this many times. This is probably my 30th launch,” she says.

The scientific goal of this project is to study the atmosphere. As the eclipse’s shadow moves across the United States from south to north, it will temporarily cool the air. Borden says it’s like dragging a swizzle stick into hot coffee.

“The eclipse itself is sort of disturbing the atmosphere as it moves across the country,” Borden said. “What we’re looking for is any sign of shadow movement, or its effects.”

Balloons are a great way to train students. “It’s the epitome of a NASA launch, but it’s cheap, it’s fast, and if it fails, you can try again,” Mary Borden says.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

Balloons are a great way to train students. “It’s the epitome of a NASA launch, but it’s cheap, it’s fast, and if it fails, you can try again,” Mary Borden says.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

The results will teach researchers more about how heat moves through the atmosphere. This data could potentially be used to improve predictions of both weather and climate change.

There is no better vehicle than a balloon to make these measurements. Unlike rockets, balloons can float gently within the eclipse zone for minutes to hours. and fly at an altitude of 75,000 to 80,000 feet. This is twice the altitude reached by a typical airliner.

Grammer says the view must be amazing.

“It would be nice to have livestream video from the balloon in flight,” he says. “You’ll see the shadow move across the globe. That’s going to look really cool.”

runaway balloon

The test launch seemed to be going smoothly, but just as Siddiqui began checking to make sure the balloon had enough lift, it suddenly broke free and shot skyward.

Third-year student Daniel Grammer will serve as flight director for the April 8 solar eclipse launch. “Everyone here is volunteering to do it because they want to do it,” he says.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

Third-year student Daniel Grammer will serve as flight director for the April 8 solar eclipse launch. “Everyone here is volunteering to do it because they want to do it,” he says.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

The entire team watches as one of the two balloons slowly drifts away.

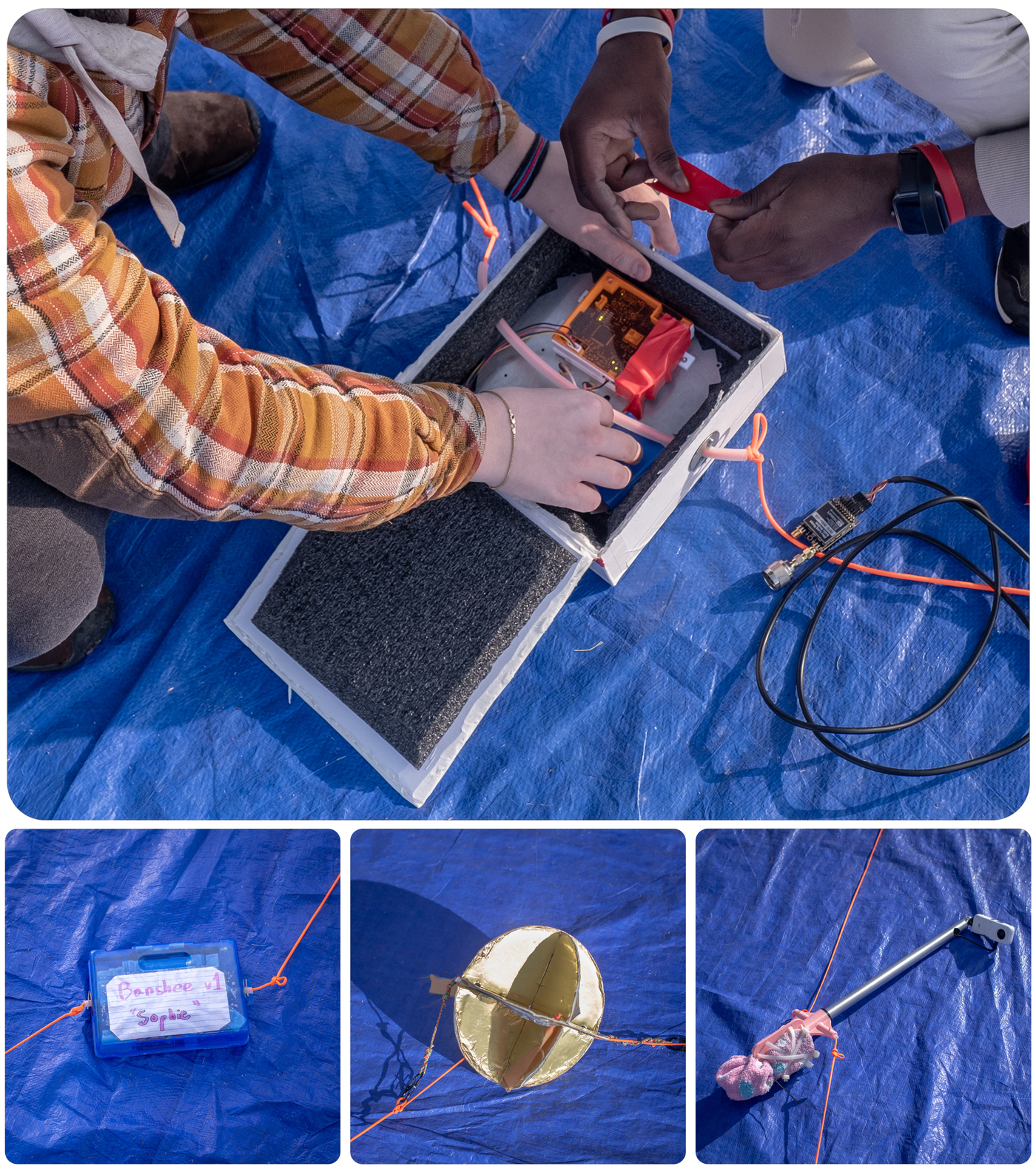

No one panics. The students put their heads together to figure out what happened. It turned out that he had forgotten to reset the device that was supposed to cut the cord at the end of the flight. This usually causes the balloon to rise and the scientific equipment to be parachuted back to the ground, where it can be retrieved.

Instead, the device detached the balloon before the payload was attached.

“I’ve never seen anything like that!” Meredith Embry says with a laugh. Juniors are in charge of tying scientific equipment to balloons.

“Fortunately, we didn’t lose any payload and always brought two extra balloons and twice as much helium as we needed,” Embry said. “Now start blowing it up and make another balloon.”

It’s a learning moment, and that’s exactly what matters.

Balloons are the perfect vehicle for studying solar eclipses. They can fly higher than aircraft and remain in the eclipse zone longer than sounding rockets.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

Balloons are the perfect vehicle for studying solar eclipses. They can fly higher than aircraft and remain in the eclipse zone longer than sounding rockets.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

“The great thing about this program is that it’s actually an educational program as well as a research program,” said Angela De, a physicist at Montana State University and principal investigator of the National Eclipse Balloon Project. Jardin says.

More than 750 students in 53 teams across the United States are participating in this project. Up-and-coming engineers are responsible for everything from scientific instruments to flight directions, weather forecasts, tracking stations, and more.

(Left) Jeremy Snyder, David Salaco, and Rain Weiser track a balloon from the ground. (Right) Launch director Kurti Binradia gives instructions to the team.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

(Left) Jeremy Snyder, David Salaco, and Rain Weiser track a balloon from the ground. (Right) Launch director Kurti Binradia gives instructions to the team.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

“We try to give these students opportunities outside of the classroom,” she says. The eclipse balloon is a “science project to give people a little taste of what it’s like in the real world to work in aerospace.”

Balloons are the perfect prelude to a rocket launch, Borden said. “This is the epitome of a NASA launch, but it’s cheap and fast, so if it fails, you can try again.”

That’s exactly what the team is doing now. Having fixed the string cutting device, they race to inflate another balloon. The wind is getting stronger, so we have to hurry. Siddiqui seems to love using engineering to solve problems on the fly under pressure. She hopes to one day get a job launching rockets, she said.

“Maybe a full-time job would be something like a flight controller/flight operator,” she muses as she watches the second balloon fill.

Meanwhile, Embry and her fellow tie-up specialist Dan Grybok are making final checks on the scientific equipment. They use red tape to cover the box containing the camera, measuring equipment and transmitter.

Students prepare their luggage before the flight. The equipment includes cameras, tracking devices, and sensors to monitor conditions above Earth.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

Students prepare their luggage before the flight. The equipment includes cameras, tracking devices, and sensors to monitor conditions above Earth.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

“Duct tape is indeed an engineer’s best friend,” Grammer jokes as he watches.

unload!

The radio blares as the flight director, a feisty senior named Kurti Bingradhya, issues orders to the team.

“We hope you’re all ready, but if you’re not yet, please let us know right away,” she says.

A payload is associated with each balloon. Other students stand around, reaching toward the floating sphere, careful not to hit anything in the final moments before launch.

Bingradhya has called for debris to be removed from the launch area. Then she looks around. The team is ready.

“Three…two…one…release!” she says.

And the students cheer as they watch their hard work disappear into the clouds.

A balloon loaded with scientific equipment flies towards the sky. On the day of the solar eclipse, dozens of teams will launch hundreds of balloons to study the atmosphere.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo

A balloon loaded with scientific equipment flies towards the sky. On the day of the solar eclipse, dozens of teams will launch hundreds of balloons to study the atmosphere.

NPR’s Meredith Rizzo