Twenty-five years ago this week, NASA launched the Chandra X-ray observatory, opening new eyes to the cosmos and showing astronomers unimaginably violent environments, including exploding stars and black holes. But the Chandra mission may soon be coming to an end, as NASA’s science division faces a nearly $1 billion budget shortfall.

NASA said it could no longer afford to continue funding Chandra, which it has been doing since it launched in 1999. The space agency has cut its science mission budget this year and cuts could continue next year because of government spending caps. An agreement was reached between Congress and the Biden administration. Last year, it halted raising the federal debt ceiling.

Congress and the White House have prioritized funding for NASA’s human spaceflight programs — primarily the rockets, spacecraft, landers, spacesuits and rovers needed for the agency’s Artemis program to return astronauts to the moon — while funding levels for NASA’s science mission division have declined.

Mark Crump, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said the space agency has no plans to shut down Chandra, but it has to find ways to cut costs somewhere.

“This is a zero-sum game discussion, so if we keep Chandra operating at its previous level, we’re cancelling out something else,” Crumpen told NASA’s Astrophysics Advisory Committee on Tuesday. Crumpen said NASA is trying to balance the costs of continuing to operate aging missions like Chandra with spending on next-generation telescopes, such as large observatories to search for habitable planets around other stars.

Scientists are trying to fight the proposed budget cuts, but time is running out. NASA’s current budget ends on September 30, and dozens of scientists and engineers who operate Chandra will lose their jobs when next year’s budget goes into effect. Grant Tremblay, an astronomer who works on Chandra, said: Administrators said they would be issuing notices of termination. Their jobs are due to end at the end of September.

“Most astronomers have families, their kids are in school, they’re established in society, so a great many of them will be forced to leave astronomy,” Tremblay said.

Chandra is the most powerful X-ray telescope ever built, with optics and detectors that sense the glow from debris scattered by the catastrophic explosion of an old star. Chandra’s high-resolution imaging capabilities make it a black hole hunter. Although astronomers cannot observe black holes directly, the X-rays emitted by the material swirling around them provide insight into their structure and behavior.

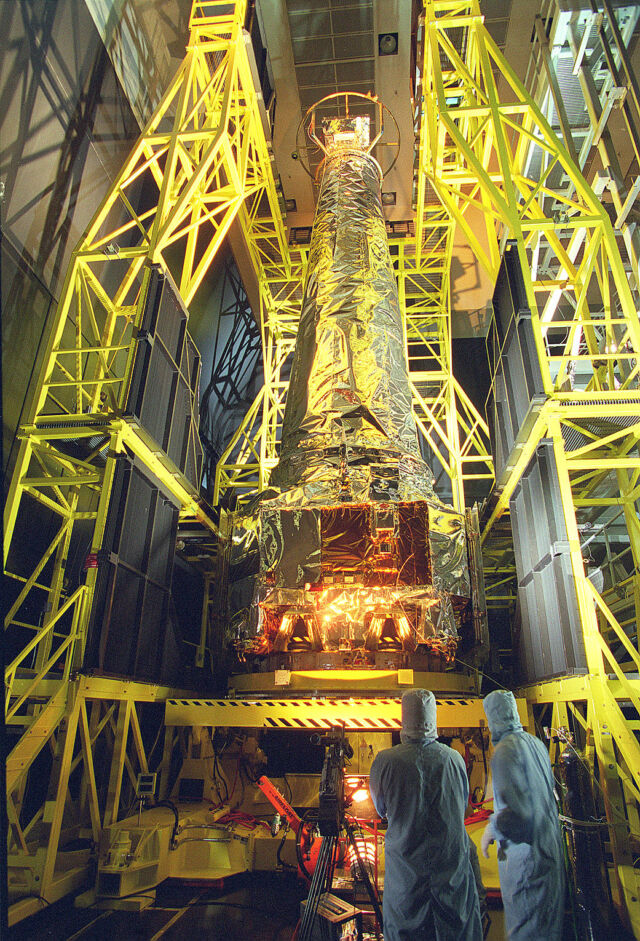

Named after the late Indian-American astrophysicist Subramanian Chandrasekhar, the observatory orbits Earth in an elliptical orbit, traveling one-third the distance to the Moon. X-rays cannot penetrate Earth’s atmosphere, so telescopes must be placed in orbit to observe them. Astronomers often combine Chandra’s X-ray data with similarly sophisticated observations of other wavelengths of light from the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes.

“For a quarter century, Chandra has made one amazing discovery after another,” Pat Slane, director of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center, said in a NASA press release. “Astronomers have used Chandra to explore mysteries unknown when the telescope was built, including exoplanets and dark energy.”