These figures represent only a small fraction of the total banking industry loan balance, but some banks are more affected than others.

From WOLF STREET by Wolf Richter.

Banks are still very profitable. The FDIC reported yesterday that the banking industry had quarterly net income of $64 billion in the first quarter. So, as an industry, banks can tolerate large credit losses, and credit losses are starting to mount. But some banks are more exposed and vulnerable than others.

Banks on the FDIC’s “problem bank list” In Q1, out of the 4,000+ banks in the US, there were 63 (blue columns), up 11 from the previous quarter. While the FDIC doesn’t release bank names, we can guess at potential candidates. So there will be more bank failures. They happen almost every year.

Total assets on the problem banks list increased by $16 billion in Q1 to $82 billion, the third consecutive quarter of decline (red line), primarily due to the CRE quagmire they find themselves in. This chart provides a historical context for the financial crisis.

CRE is starting to leave skid marks.

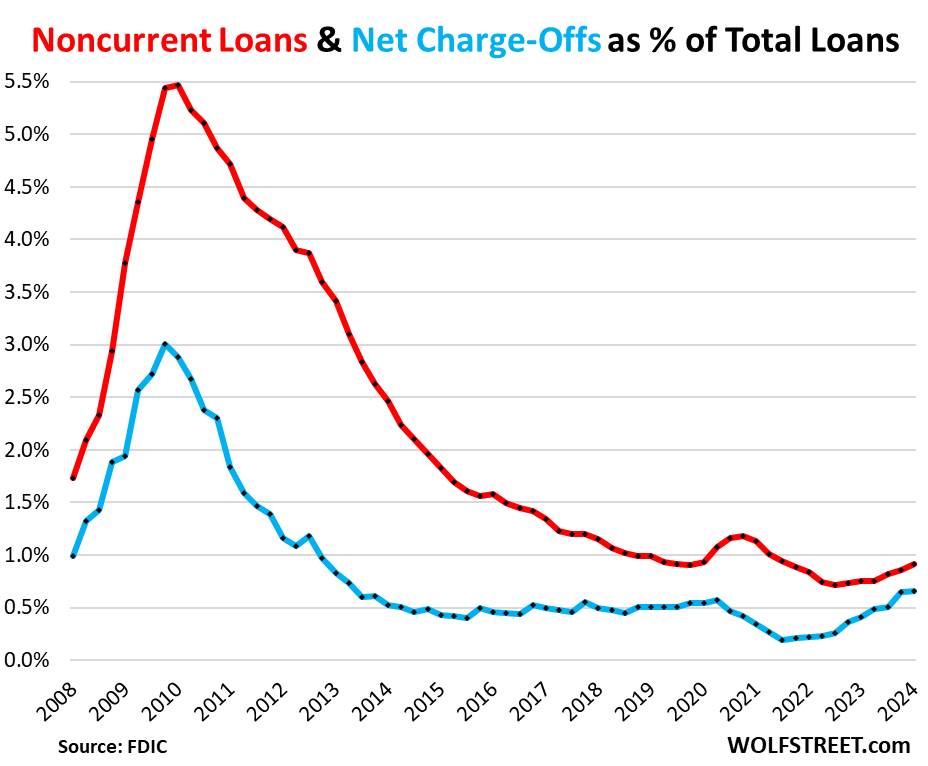

Illiquid Loans The rate of default on loans rose to 0.91% of total loans (from 0.86% in the previous quarter), now roughly the same as during the boom period just before the pandemic, and reached 5.5% (in the red) at its peak during the financial crisis.

The deterioration was driven by CRE loans, with large banks’ office portfolios pushing illiquid rates up to 1.59%, the highest since the fourth quarter of 2013.

Net allowance for credit losses At 0.65% of total loans (the point at which banks give up on loans), it was the same as the previous quarter but up from historic pandemic-era free money lows and slightly higher than during the pre-pandemic economic boom. The driving force behind the rise in free money from lows in 2022 was credit cards, with the net charge-off rate rising to 4.70% in the first quarter, up 122 basis points from the pre-pandemic average. Here, we take a closer look at those who are behind on their credit card payments.

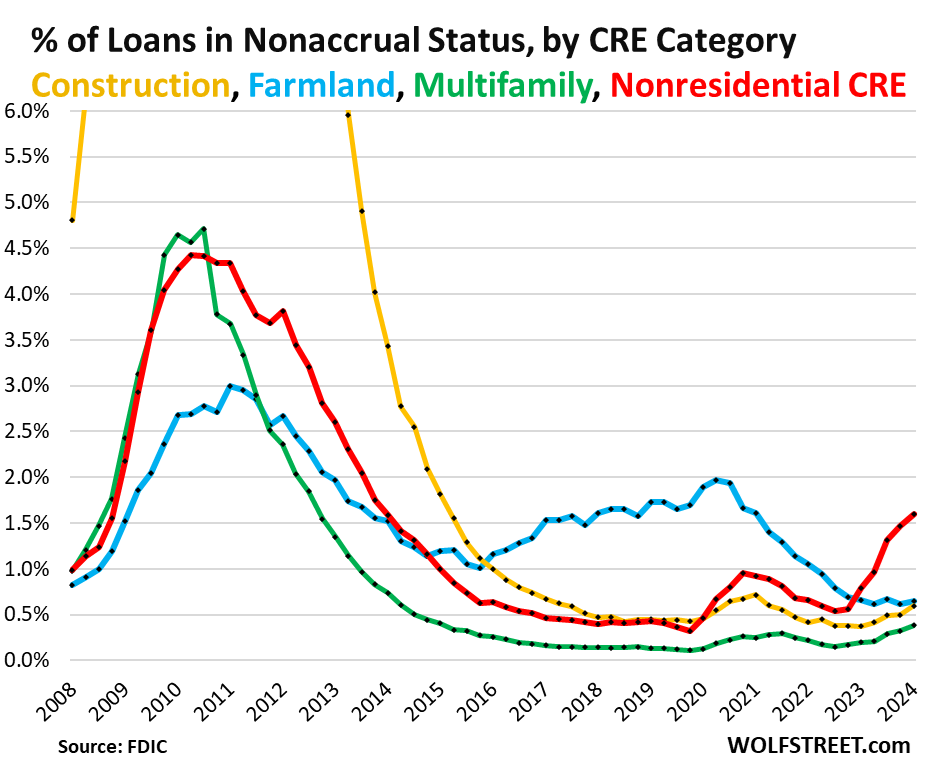

Accrued interest payment ratio by CRE category.

The chart below shows that non-residential non-agricultural CRE loans (red) are outliers in terms of non-accrual ratios compared to other CRE categories such as construction loans (yellow), farm loans (blue), and multifamily loans (green).

Non-residential CRE loans from major banks are becoming more complicated.

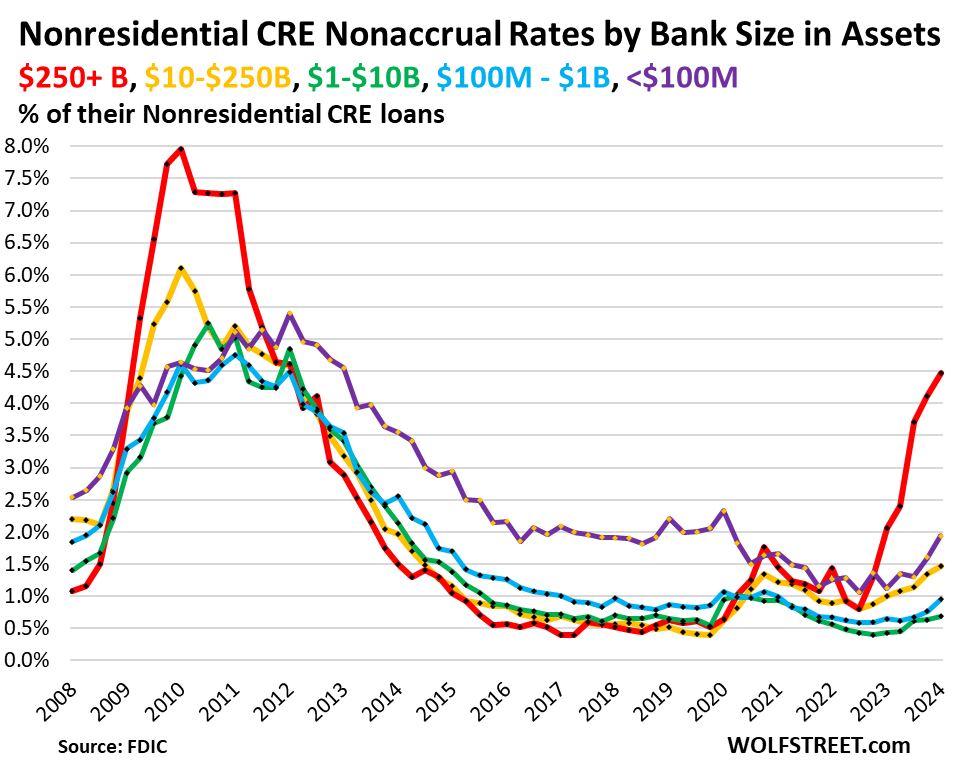

The FDIC provides delinquency data by bank size for nonresidential nonfarm CRE loans (which includes office and retail, the most problematic sectors of CRE lending), and the “delinquency and nonaccrual rates” for these CRE loans have increased across all bank sizes.

However, for large banks with over $250 billion in assets, interest rates on non-residential CRE loans have skyrocketed to 4.48% of all non-residential CRE loans (red in the graph below).

During the financial crisis, a big part of the blame was on mortgages, a much larger loan category than non-residential CRE loans. At present, mortgages remain in good condition, with delinquencies and foreclosures at historically low levels.

For smaller banks with less than $100 million in assets, the “delinquency and non-accrual rate” jumped to 1.94% of non-residential CRE loans (purple).

Thankfully…

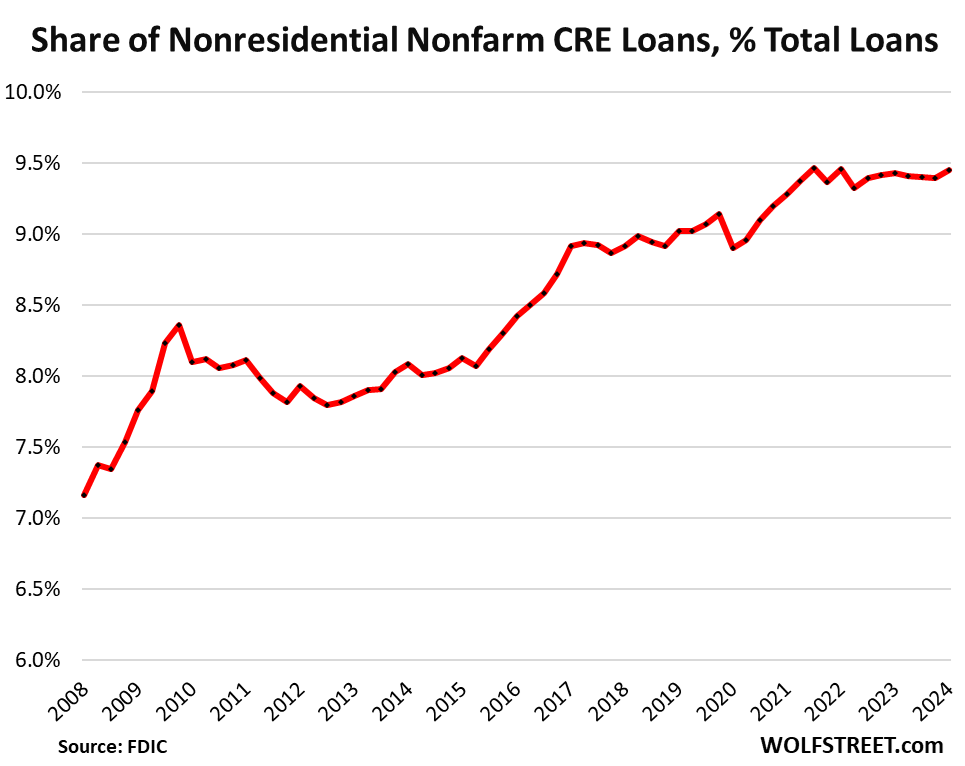

Non-farm, non-residential CRE loans, where the majority of the lending problems are currently occurring, only make up a small portion of banks’ overall loan book. In the first quarter, these loans made up 9.4% of total bank loans. For 2021 and beyond, that percentage has remained in roughly the same range, just below 9.5%. And the fact that they aren’t a large percentage of the overall loan book is a good thing, given how problematic these CRE loans will be over the next few years as the sector cleans up, so to speak.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support us? You can donate, we’d be so grateful! Click on Beer and Iced Tea Mugs to find out how.

Want to be notified by email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()