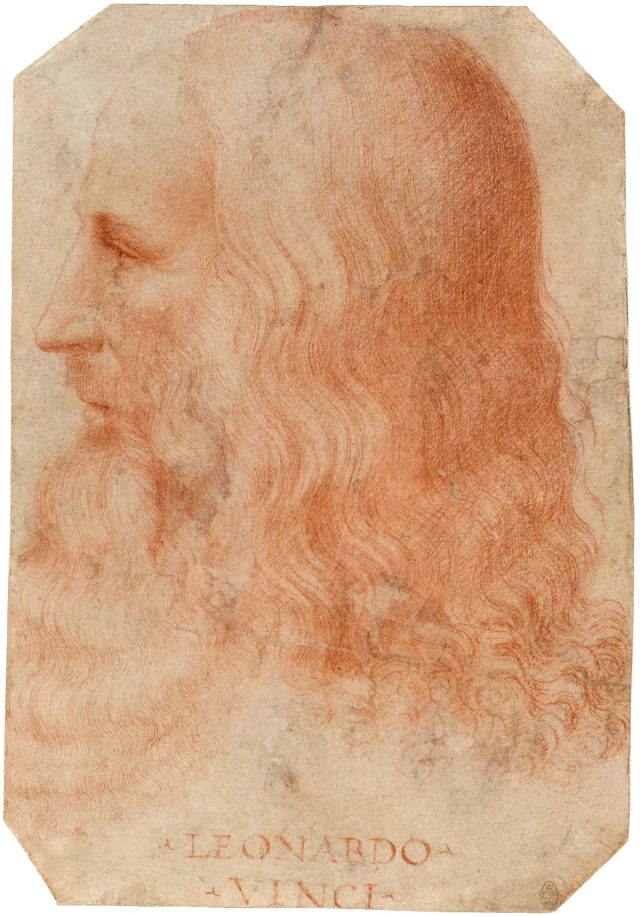

public domain

Was Leonardo da Vinci’s mother, Caterina, a slave kidnapped from the Caucasian mountainous region of Central Asia? is the latest hypothesis to rekindle the long-running debate about historians. Carlo Becce of the University of Naples told reporters At a press conference on Tuesday, he uncovered previously unknown documents that backed up that claim.Il Sorriso di Caterina again Katerina’s smile) based on his research.

Leonardo born 1452, illegitimate son of a Florentine notary Ser Piero D’Antonio and a woman named Caterina. Cell He Piero married a woman named Albiera He Amadori, and after her death in 1464 three marriages followed. His various unions produced 16 children (11 of whom survived early childhood), in addition to Leonardo, who grew up in his father’s household and received a solid education.

As for Caterina, many historians consider her to be a local peasant girl and eventually a kiln worker named Antonio di Piero del Vacca (called “Raccatabriga” or “quarreler”). identified as the wife of But that’s all we know about her. Perhaps most controversially, Italian historian Angelo Paratico proposed in his 2014 that Caterina was imported from the Crimea by Venetian merchants and sold to Florentine bankers as a Chinese domestic that they were slaves.

public domain

Paratico book, Leonardo da Vinci: The Lost Chinese Scholar in Renaissance Italy, was published the following year. His theory, based in part on the work of Renzo Chanchi in Vinci’s Leonardo Library, proposed that Caterina was a slave belonging to one of Ser Piero’s wealthy friends. According to the New York Timesit is also a hypothesis for an upcoming book on Leonardo’s genealogy by Alessandro Vezzosi, director of Leonardo da Vinci Heritage.

Renowned Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp of the University of Oxford took a different direction by arguing in his 2017 book: Mona Lisa: people and paintings (with Giuseppe Palanti), Caterina was an orphan at the age of 15. Kemp found evidence that a girl of that age named Caterina di Meo Lippi lived less than a mile from Vinci with her younger brother Papo. She may have become pregnant when Ser Piero visited her hometown. Among the evidence is Antonio da his Vinci’s 1458 tax return, which confirms that Leonardo, then five years old, lived in his house.

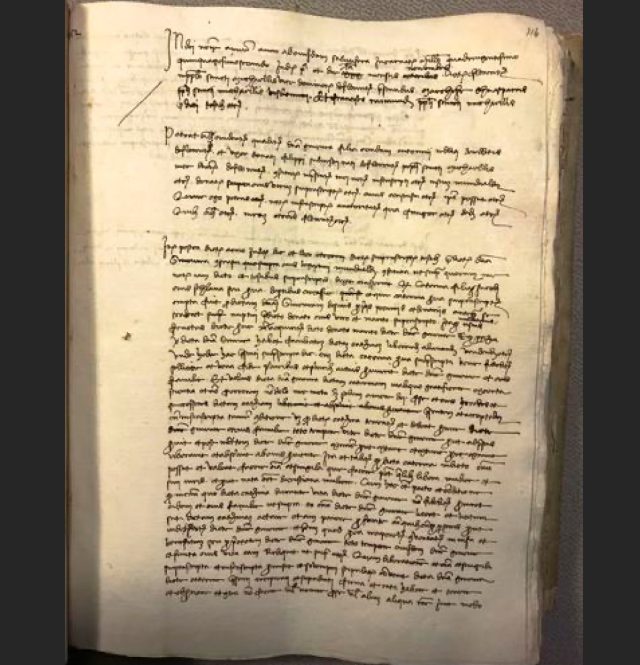

As for Vetsche, he admitted that his own research was “guided” by the slave hypothesis put forward by Paratico and Vetsosi, but initially resisted the idea. found a document dated November 2, 1452, freeing an enslaved Circassian woman named Caterina on behalf of her mistress, the wife of Donato di Felippo di Salvestro Nati. The notary who signed the document was none other than Leonardo’s father, Ser Piero.

Carlo Vecche via AP

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the document.” Vecce told NBC News“I have never believed the theory that she was a slave from abroad. So I spent months trying to prove that the notary Caterina was not Leonardo’s mother.” But in the end all the documents I found went in that direction, and I was succumbed to the evidence. Met [that] Ser Piero has written all of his long career. Additionally, this document is full of small errors and oversights. This is a sign that impregnating someone else’s slave is a crime, and perhaps he was nervous when he drafted it.

A healthy dose of skepticism is warranted here, and Vecce has yet to publish an academic paper detailing his findings. (Seems to be in progress.)

“Carlo Becce is a fine scholar.” Kemp told NBC News“His ‘fictional’ account requires a sense of a slave mother.” I still advocate for the more suitable ‘country’ mother, especially as the future wife of a local ‘farmer’. It doesn’t match the general need for stories. ‘ At the end of the day, Kemp added, ‘None of the stories have been definitively proven.