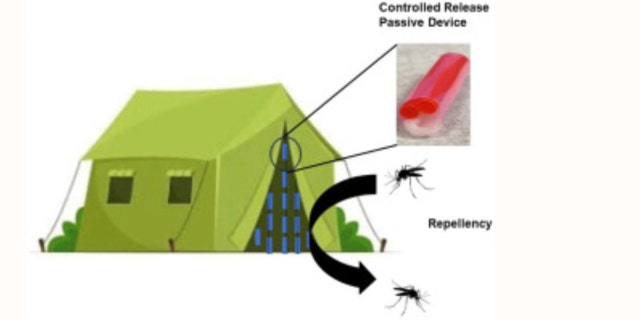

A new device developed at the University of Florida provides long-term protection for members of the US military from mosquitoes.

The university said the device, which is funded by the Department of Defense’s Deployed Fighter Protection Program, does not require heat, electricity, or skin contact.

Designed by PhD Nagarajan Rajagopal. candidate, and Christopher Batich from the school’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

According to a press release, it was recently successfully tested in a four-week semi-field trial at the Gainesville Department of Agriculture, which resulted in the controlled release of the repellent transfluthrin, allowing multiple species of mosquitoes to reach the test site. was shown to be effective in preventing intrusion into

PETA claims Navy victory to end ‘horrific’ tests on sheep

A new device developed at the University of Florida provides long-term protection for members of the US military from mosquitoes.

(U.S. Navy File)

Transfluthrin is an organic pesticide considered safe for humans and animals.

The repellent consists of a 2.5 cm long tube of polypropylene plastic containing two small tubes and a swab containing the repellent.

Rajagopal said in a statement that the researchers used fishing line to attach 70 devices to the openings of a large military tent and none to a similar control tent. The caged mosquitoes were released at different locations along the outside of the tent and within 24 hours, nearly all of them were killed or repelled.

As part of testing the new repellent device, caged mosquitoes were released at various locations along the outside of the tent and nearly all were killed or repelled within 24 hours.

(Reuters / CDC / James Gathany / File)

Overwintering monarch butterflies in California recover for second year in a row

Mosquitoes have the ability to spread diseases and viruses such as malaria, dengue virus, Zika virus and West Nile virus.

Rajagopal said a patent for the mosquito repellent device is pending and the government is interested in further research so that it can eventually be commercialized for the private market.

Researchers at the University of Florida have developed an insect repellent device for the US military.

(University of Florida)

Field tests have shown that the prototype creates a mosquito-protected space for four weeks, but the final product, built using a 3D printing process, extends that time to up to three months. There is a possibility. In addition, USDA will evaluate other ingredients to expand their capabilities.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“It doesn’t stop at mosquitoes,” said Rajagopal. “We want to show that it works against other insects that pose a threat to Lyme disease, especially ticks.”