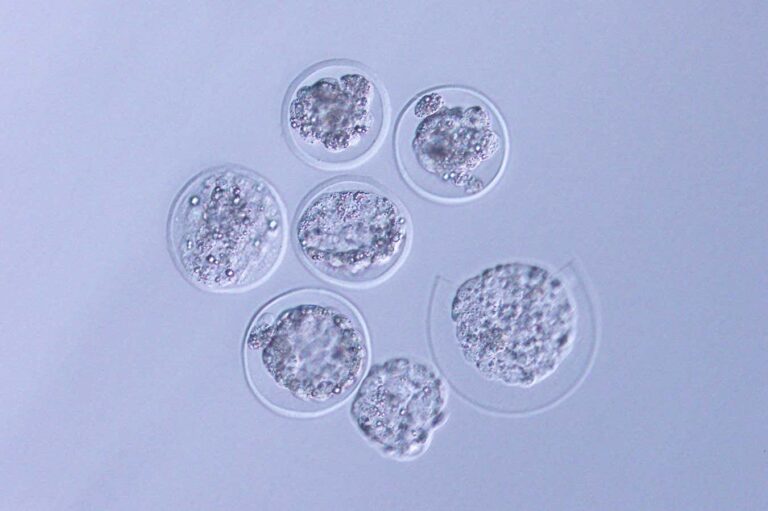

Microscopic image of a mouse embryo returned from the International Space Station

Teruhiko Wakayama/University of Yamanashi

Mouse embryos have been cultured for the first time on the International Space Station (ISS) to test whether it is safe for humans to become pregnant in space.

“A trip to Mars takes more than six months, so it’s possible that you could become pregnant during a future trip to Mars.” Teruhiko Wakayama A doctor from the University of Yamanashi in Japan led the study. “We are conducting research to ensure that we can safely give birth to children when that time comes.”

Wakayama and his colleagues carried out the first steps of the experiment in a lab on Earth, extracting and freezing embryos at the early two-cell stage from pregnant mice.

The frozen embryos were sent to the ISS aboard a SpaceX rocket launched from Florida in August 2021. They were stored in special equipment designed by Wakayama’s team so that astronauts on the station could easily thaw the embryos and culture them for four days. The astronauts then chemically preserved the embryos and sent them back to Earth on the return craft.

Wakayama said the embryos only grew for four days because they can only survive outside the uterus.

His team studied the returned embryos to see if their development was affected by exposure to high levels of radiation and low gravity. Outer space is known as microgravity.

The fetus showed no signs of DNA damage from radiation exposure, likely because it was only in space for a short period of time.

They also showed normal structural development, including differentiation into two cell groups that form the basis of the fetus and placenta. This was an important discovery, Wakayama says, because it was previously thought that microgravity could affect the ability of embryos to separate into these two different cell types.

It’s unclear whether being in space disrupts later stages of embryonic development, but a previous study in which pregnant rats were sent on a NASA spaceflight for 9 to 11 days late in pregnancy found that fetal development was disrupted. There was found. I gave birth to a normal weight puppy. It was suggested that the pups grew normally when they returned to Earth.

“based on [this] And our results show that space reproduction in mammals is probably possible,” says Wakayama.

But it’s still unclear whether microgravity conditions actually make it difficult to deliver mouse pups or full-term human babies, he says.

His team now plans to test whether mouse embryos sent to the ISS and returned to Earth can be implanted into female mice and grow into healthy offspring. This could provide further clues about the viability of embryos exposed to cosmic radiation and microgravity. The researchers also hope to test whether mouse sperm and eggs sent to the ISS can be used to create embryos through in vitro fertilization in space.

topic: