I read a lot of press releases about new scientific papers for my work. Sometimes the art that accompanies them is interesting. fuchsia rendering of microscopic organisms sacolitasSometimes they are reminiscent of past worlds. Reconstruction of crabs from 100 million years agoSometimes these images are ambitious infographic Also A disturbing act in Photoshop. Ostensibly, the purpose of these images is the same. Getting people to click on articles about something new we discover about the world.

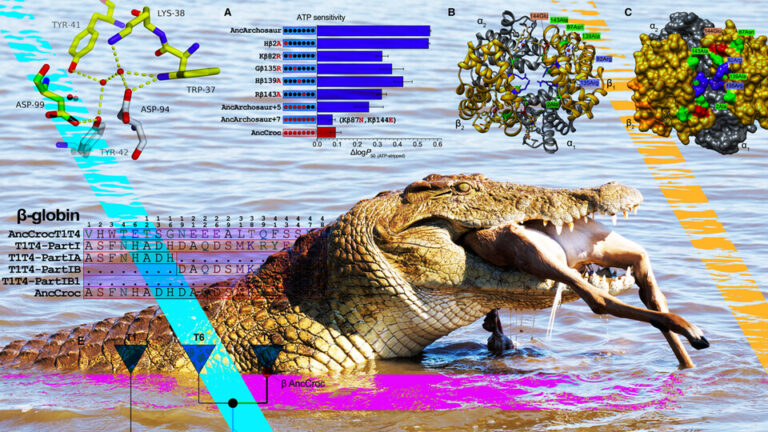

On Thursday, while scrolling through the press releases, there was an image that stopped me. On one level, it was a picture of a Nile crocodile rising out of the water with half of an ungulate known as an impala hanging from its teeth. But it was also an artistic collage of rendered molecules, charts, and his three neon lines running through water a crocodile had just killed. These visual details were so striking that when I first saw the image, I almost missed the half-swallowed Impala, as if an alligator teleported to his 1990s, Portland International Airport It was like hunting in the famous teal carpet of I definitely wanted to click. But this image also did what great art should do. It got me thinking. I wanted it as a T-shirt.

I saw the image on Phys.org, a site that aggregates science and technology news. It was accompanied by a press release.Research unravels the mystery of crocodile hemoglobinspotlighted the results of a new study in the journal biology today It was published by a group of scientists including Jay F. Storz, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The press release was written by Scott Schrage, a writer at the University of Science. But who created that image? University Communications and Marketing. Scott Schrage!Writer When artist. i needed to talk to him.

Schrage, who has been writing about university research for about seven years, is responsible not only for writing scientific papers published by universities, but also for finding the images that accompany them.Sometimes this secondary task is easy and Storz and his colleagues Posing with penguins at the Omaha Zoo To promote a new paper on the evolution of hemoglobin in penguins. (Storz is really into hemoglobin. His team Capturing high-altitude mammalsIt is a yellow-billed mouse that lives over 22,000 feet above sea level, but has only about 44% of the oxygen available at sea level). This means Schrage had to innovate.

“Walking through these huge oceans of text, like 15 to 20 pages of paper, there is a visual appeal of these beautiful little islands,” Schrage says, referring to the charts and renderings that paper often contains. “They kind of delve into some technical stuff beyond the scope of the story I’m trying to write, but that’s exactly what it is.” He said, So Schrage began experimenting, creating images that combined paper visual elements with stock photography.

Storz told Schlage that he had always been interested in the images of alligators seen in nature documentaries. Watch large reptiles lurk below the surface, leap out of the water, drag their prey into the water and drown them. 1 hour or moreCrocodiles are able to do this because they have evolved a special way of regulating their hemoglobin, “a slow-release mechanism that allows crocodiles to efficiently utilize their body’s oxygen stores,” Stoltz says. told Schlesi in a press release. (To learn more about the new research, be sure to read on. The story of Schrage, which is much more complete and subtle than this. )

Schrage began looking for stock photos of alligators ambush prey in the water. “This particular image I just thought of was incredibly compelling,” he said. ‘s droopy legs reminded me of Tom and Jerry cartoons. The tail hanging out of Tom’s mouth may have been the only hint that Jerry was in trouble.

Next came stripes. “We felt we needed something to frame the crocodile,” Schrage said, adding that he arranged the stripes in a way reminiscent of the tree of evolution. He turned to his ’90s colors his palette. A blue-green stripe, reminiscent of the colors of the Charlotte Hornets, came first, then an orange creamsicle, and then a fuchsia stripe at the bottom. I often try to include in my images, but I was worried that the bloody red would be too nosebleed in the watery hunting context. Besides, crocodile hunting is not necessarily killing. “It’s drowning, doing a death roll on its prey,” Schraj said. “More or less, especially with prey like impalas, it just swallows it.”

Schlage superimposed a diagram from this study on the image. Here are some charts and renderings of hemoglobin resurrected from ancient crocodile ancestors. He also included the actual genealogical tree of the paper in the lower left corner. “Looking at these, I thought it looked like a very rudimentary representation of a crocodile’s teeth, like a child,” he said. “So we were like, OK, let’s include that element as well.”

All these elements combine to create a completely unforgettable scientific image. When I asked his Schrage if he considered himself a maximalist, he disagreed. Institutional writing often involves guidelines, many editors, and many eyes asking the publication to have a say. he said. “I have more freedom when it comes to this.”

Schrage said he feels fortunate to be able to cover this type of research. Reconstructing hemoglobin from hundreds of millions of years ago seems almost like science fiction. increase. My own humble hemoglobin rushing through my bloodstream, a breathtaking image.