National Archives / Renaud Moreu

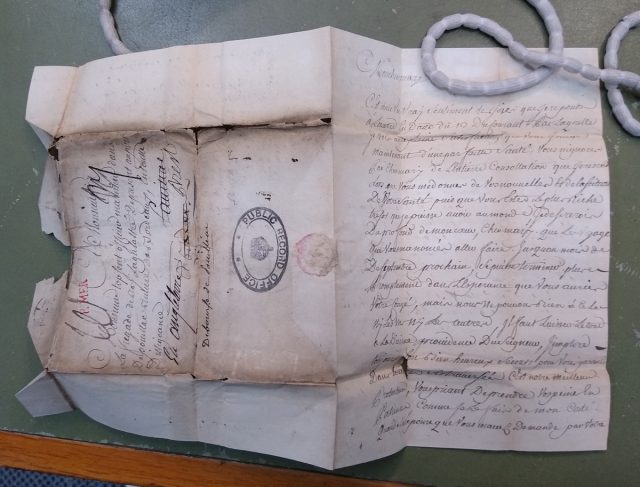

Renaud Moreu, a historian at the University of Cambridge, was poring over documents at the National Archives at Kew when he came across a box containing three piles of sealed letters held together with ribbons. Archivists gave him permission to publish letters from his loved ones to his 18th-century French sailor. All of these letters had been seized by the Royal Navy during the war. seven years war (1756-1763).

“I realized that I was the first person to read these very personal messages since they were written.” Morrieux said., he has just published an analysis of the letter in the journal Annals Histoires Sciences Sociales. “These letters are about the universal human experience, not specific to France or the 18th century. They reveal how we all deal with life’s great challenges. When we are separated from our loved ones by events beyond our control, such as pandemics or wars, we must think about how to stay in touch, provide reassurance, care for others, and maintain our passion. Now we have Zoom and WhatsApp. In the 18th century, people only had letters, and what they wrote feels very familiar.”

Britain and France have a long and complicated history of war. hundred years war In the 14th and 15th centuries. The two countries continued to be at war almost continuously during the 18th century, with Britain and France attempting to establish global dominance with the aid of their respective allies in Europe, the Americas, and the Asia-Pacific. This includes the Seven Years’ War fought. . The war technically began in the North American colonies, when Britain sought to expand into territory already claimed by France. (Fun fact: 22-year-old George Washington led an ambush against French troops in 1754. Battle of Jumonville Glen) However, the conflict soon spread beyond the colonies’ borders, and Britain continued to seize hundreds of French ships at sea.

National Archives / Renaud Moreu

According to Morieux, despite amassing an excellent fleet of ships during this period, France lacked experienced sailors, and by 1758 nearly one-third of all French sailors were imprisoned by the British. However, it did not solve the problem. Although many sailors eventually returned home, several died during their imprisonment, usually from malnutrition or disease. Delivering messages from France to ships that were constantly on the move was no easy task. Multiple copies were often sent to different ports to increase the chances that the letter would reach its intended recipient.

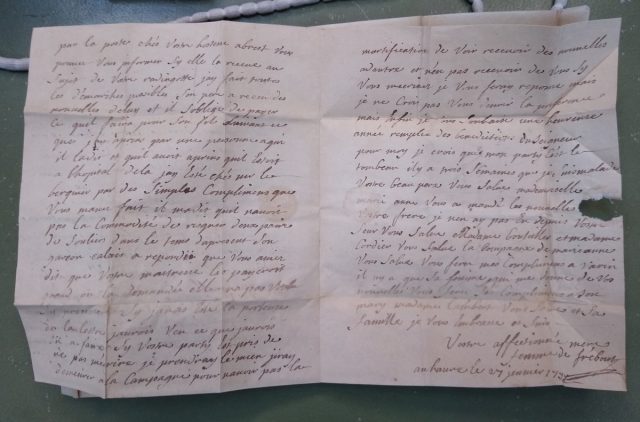

This particular bundle of letters was addressed to various crew members of a French warship. GalitiansIt was captured by a British ship called . essex 1758, en route from Bordeaux to Quebec. Moreu’s genealogical research investigated his entire crew. Naturally, some of the letters include one in 1758 in which Marie Dubosc wrote to her husband, a ship’s lieutenant named Louis Chambrelin, professing to be his “eternally faithful wife.” Also included were love letters from her wife to her husband. According to Moreau’s research, Marie died the following year, before her husband was released. Although Chambrelin received no letters from his late wife, he remarried upon his return to France.

Morrieux read several letters from his 61-year-old mother Marguerite and fiancée Marianne, addressed to a young sailor from Normandy named Nicolas Quesnel. Marguerite’s letters reprimanded the young man for frequently writing to Marianne instead of her, reinforcing her feelings of guilt. “I think of you more than you,” her mother wrote (or, more likely, dictated to her by a trusted scribe), adding, “I think I should go to my grave. , I’ve been sick for three weeks,” he added. (Translation: “Before I die, why don’t you write a letter to your poor sick mother?”)

National Archives / Renaud Moreu

Apparently, Quesnel’s neglect of her mother has caused tension between her and her fiancée since Marianne wrote to her mother three weeks later asking her to remove the “black cloud” in the household. . But Marguerite didn’t mention her father-in-law at all in the letters Quesnel sent home, so she only complained that the poor young man couldn’t really win. According to Morieux, Quesnel survived his imprisonment and ended up working on a transatlantic slave ship.

For Moreu, reading the letters shed new light on the lives of sailors and their families, especially women. “These letters show that people are coming together to meet challenges.” He said. “Today, we are very reluctant to write a letter to our fiancé, knowing that our mothers, sisters, uncles, and neighbors will read it before we send it, and that many others will read it once we receive it. It’s hard to tell someone what you really think.”

Annales Histoire Sciences Sociales, 2023. DOI: 10.1017/ahss.2023.75 (About DOI). (in French)