newYou can now listen to Fox News articles.

In the fall of 1864, both Union and Confederate armies in the Shenandoah Valley found themselves trapped in a cycle of violence and retaliatory deaths. The Civil War is full of nuance, tragedy, unexpected sacrifices and triumphs of the human spirit. Two such events helped end this winless and bloody cycle.

In mid-October 1864, Union soldiers placed a leather strap around the neck of Private Albert Gallatin Willis, a former Baptist seminary student. In his final seconds on earth, the 20-year-old Confederate soldier, a member of the Mosby’s Rangers, bravely prayed before his executioners.

As a member of the 43rd Battalion or Company C of the Mosby’s Rangers, Willis survived multiple skirmishes and tragic near-deaths. He was granted a furlough and was heading south to his home in Culpeper, Virginia, with another ranger when his horse went lame outside a patchwork of homes in what is now Ben Venue. Became.

The last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the Korean War is laid to rest in the U.S. Capitol.

A local blacksmith’s hammer and anvil masked the sounds of Union cavalry closing in on two unsuspecting Confederates. Outnumbered, the rebels surrendered without a fight and were taken to Colonel William Henry Powell’s headquarters. President Powell ordered one of the two men to be executed in retaliation for a Union soldier who had been executed a few days earlier.

Sergeant William T. Biedler, 16, of Mosby’s Company C, Virginia Cavalry, with a flintlock musket.

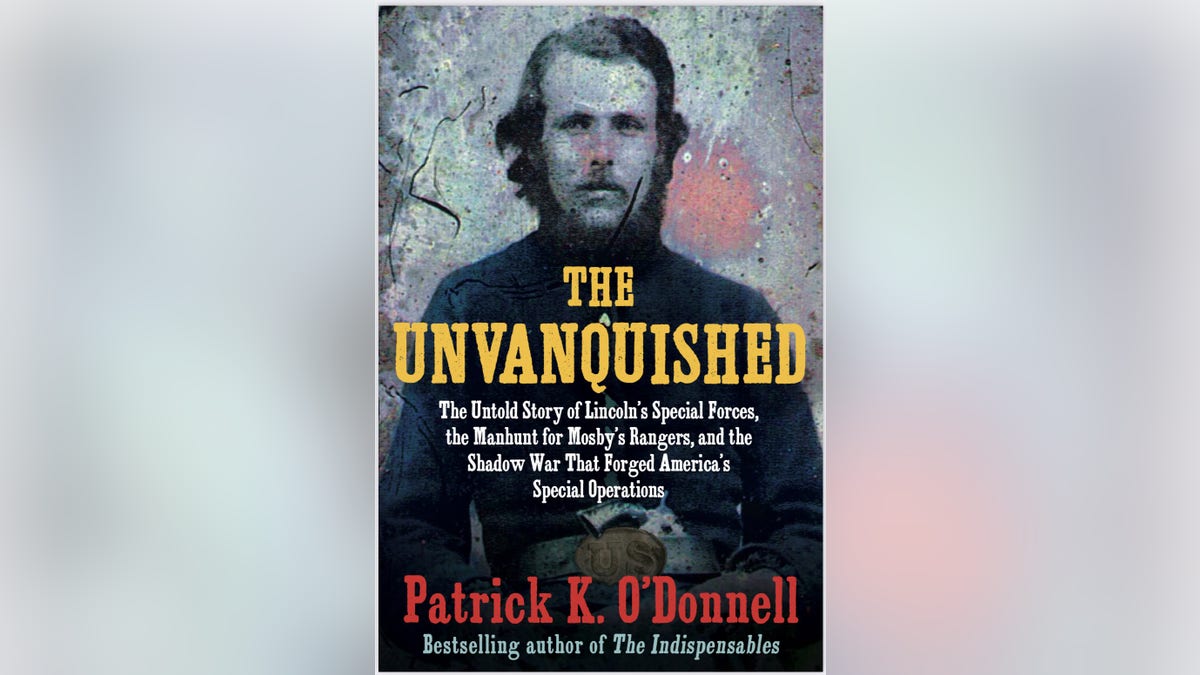

Willis’ little-known story is explored in my forthcoming book, along with the story of the Confederate intelligence and Union scouts who inspired the creation of America’s Special Forces. “Unvanquished: The untold story of Lincoln’s special forces, the search for Mosby’s Rangers, and the shadow war that shaped American special operations.”

After learning of Willis’ religious background, Powell told the young ranger he could apply for a chaplain exemption, but the private refused. Mr. Powell then ordered the two prisoners to draw straws to decide who would be hanged.

Mr. Willis’ companions drew the short straw and began to cry. “I have a wife and children, but I’m not a Christian and I’m afraid to die,” complained the unlucky man. Willis replied, “I don’t have a family. I’m a Christian, so I’m not afraid of dying.”

Unfortunately, Willis was not the last man to be executed. His wake was followed by a gruesome series of killings and retaliations.

Best-selling author Patrick K. O’Donnell’s upcoming book on the Civil War is titled “Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Search for the Mosby Rangers, and the Shadow War That Shaped America’s Special Operations.” There is.

Colonel John S. Mosby informed Confederate General Robert E. Lee of the Union executions, writing: [General George Armstrong] “Every time I get Custer’s men,” Lee agreed with Mosby’s approach to stopping the violence.

So on November 4, outside the train depot where 27 Union prisoners were being held, Mosby hatched a plan to carry out Lee’s orders. Each man took out a piece of white paper from his hat. Blank is 20. 7 is marked. The unlucky seven people will be executed.

Some men prayed loudly. Each carefully picked a piece of paper. Some people breathed a sigh of relief. Some shouted, “Oh God, please help me!” The hysterical drummer boy pulled out a blank slip and was greatly relieved. The second drummer boy was not so lucky.

Mosby heard that the boy was among those convicted and ordered his immediate release. The remaining 19 people, thinking they had cheated death (the other drummer boy was also excluded), drew lots again until someone chose Mark.

An old train depot where Col. John S. Mosby’s Confederate troops held Union prisoners of war. Graffiti by prisoners can still be seen on the walls of the building. (Patrick K. O’Donnell)

The Confederates quietly tied up the condemned men, mounted their horses, and rode to the Shenandoah Valley, where Mosby ordered four to be shot and three to be hanged.

For more FOX News opinions, click here

However, not everything went according to plan. When one of the prisoners was given time to pray, he was able to kneel down and free his hands. He jumped up, punched a nearby ranger in the face, and fled into the woods.

Surprised, the Confederates opened fire on the remaining prisoners. A second man escaped due to the misfire. The Confederates hanged the remaining three prisoners, one of whom wrote, “In retaliation for an equal number of Colonel Mosby’s men who were hanged on the Royal Front by order of General Custer, these men were also hanged.” He attached a note that read, “He will be thoroughly executed.”

So on November 4, outside the train depot where 27 Union prisoners were being held, Mosby hatched a plan to carry out Lee’s orders. Each man took out a piece of white paper from his hat. Blank is 20. 7 is marked. The unlucky seven people will be executed.

When Mosby’s men return and explain what happened, instead of executing more people, the Gray Ghost, known as Mosby, sends the Rangers to Winchester with a white flag and tells Union General Philip Sheridan I sent a letter addressed to you.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In his letter, Mosby detailed the situation, including that more than 700 prisoners were captured and sent to Richmond. He added: “Hereafter I will treat prisoners of war who fall into my hands with kindness according to their condition; however, some new act of barbarity will compel me to reluctantly adopt an inhuman policy.” “It’s different if you don’t have one,” he promised.

One of his rangers returns with a letter from Sheridan. Neither man spoke about the contents of the letter, but the revenge killings stopped.

Click here to read more articles by Patrick K. O’Donnell