Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

NEW YORK — Mary Miller Duffy was stunned and heartbroken. Her brother suddenly collapsed and became brain dead a few days later. Now she faces her tough question. Will she offer his remains for research?

Thus, the body of Maurice “Mo” Miller began its journey to a sunny corner of the intensive care unit at New York University Langone Health, part of a quest to one day alleviate the shortage of animal organs. .

“He always wanted to help people,” Miller Duffy said. Though she struggled with her choice, she is proud of her brother’s final act. “This tragic death, this rapid death, something good came out of it.”

Surgeons replaced Miller’s kidney with a genetically modified pig kidney on July 14. After that, doctors and nurses spent their days in anxiety, caring for the deceased man as well as for living patients.

Amazingly, more than a month later, the new organ is performing all the physical functions of a healthy kidney. This is the longest time pig kidneys have ever worked in the human body. Now the countdown has begun to see if the kidneys can hold out until the second month of September.

The Associated Press conducted an internal investigation into the challenges of cadaver experiments that could help bring animal-to-human transplants closer to reality.

It is extremely difficult to receive an organ transplant right now. There are more than 100,000 people on waiting lists nationwide, most of them in need of kidneys. Thousands are dying waiting. Thousands more who could benefit have not even been added to the list.

Dr. Robert Montgomery, director of the Langone University Transplantation Institute at New York University, said he had “seven cardiac arrests before he was sick enough” to qualify for a new heart transplant. He is a kidney transplant surgeon and was lucky enough to have his own heart transplant in 2018.

To fill this gap, he believes, animal organs must be used.

After decades of failed attempts, pigs genetically modified to make their organs more human-like are now renewing interest in so-called xenotransplantation. Last year, surgeons at the University of Maryland tried to save a dying man with a pig heart, but the man survived for two months.

Montgomery has more practice in the dead before working with living patients. Several previous experiments at New York University and the University of Alabama at Birmingham have kept pig kidneys and hearts functioning in donated cadavers for days to weeks, dooming many previous attempts. avoid immediate rejection.

However, the most common type of organ rejection develops over a month. Maryland pig hearts worked well for nearly 50 days before suddenly failing. Observing how a pig’s kidney reaches that point in a donated cadavers could provide important lessons, but Montgomery doesn’t know how long it takes his family to hand over their loved ones. could you have predicted

“I am in awe of anyone who can make such a decision in the darkest moment of their life and take their humanity seriously,” he said.

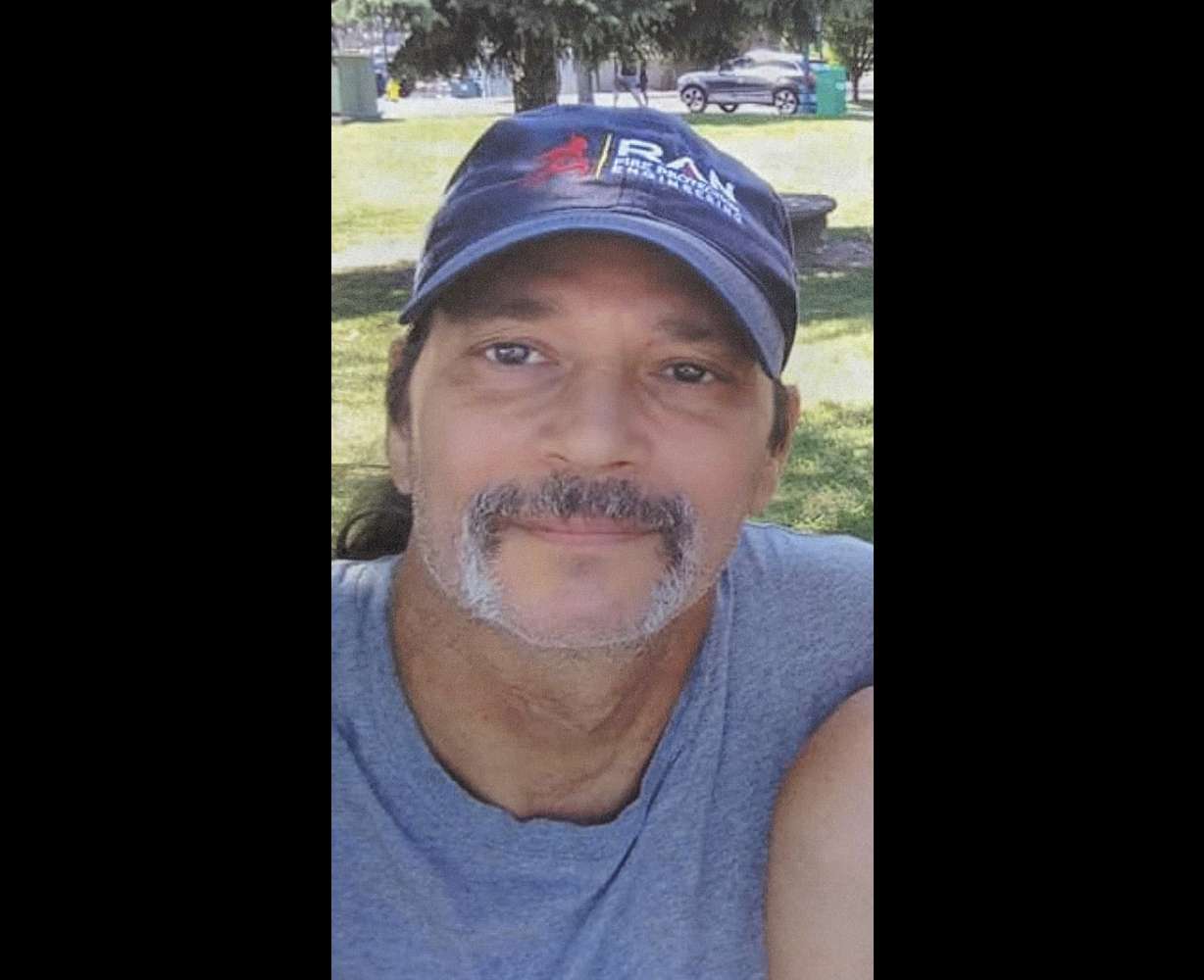

In Newburgh, New York, an ambulance rushed Miller to hospital after collapsing with a brain tumor. He never recovered from the biopsy and was brain dead at just 57. The next step rested with his closest relative, his sister.

Miller Duffy asked about organ donation, but was not eligible. The biopsy found cancer.

Only then did the Organ Agency offer whole-body donation. Miller-Duffy wasn’t familiar with it, but he said he “kind of sympathized” with the goal of improving kidney transplants. Another brother died of kidney disease when he was an infant. Other relatives also had kidney-damaging diseases and some died while on dialysis.

As Miller Duffy flips through family photos, she remembers her brother adopting animals and once caring for a terminally ill friend. Still, she had her doubts.

In a video call, Montgomery explained to Miller Duffy and his wife Sue Duffy about the pig transplant and why it makes a difference. Montgomery’s compassion captivated them.

“His body is unharmed,” said Duffy. “This is just an incubation period to do research.”

This experiment served as a one-day surgical rehearsal on live patients. Montgomery finished removing Miller’s own kidney as the helicopter headed for the hospital’s riverside landing pad. Doctors. Fellow New York University surgeons Jeffrey Stern and Adam Griesmer raced with kidneys taken from pigs raised by Blacksburg, Virginia-based Liviviker.

Stern said stitching pig kidneys into donated bodies isn’t much different than a regular transplant. Postoperative immunosuppressants are also standard.

One twist: Pig kidneys are fitted with the thymus, a gland that trains immune cells, which may help protect the organ.

Many additional steps occur before and after surgery.

The first is which pig to use. Some pigs have up to 10 genetic alterations, but Montgomery bets that one is enough for him. That means removing a single porcine gene that triggers an immediate immune attack.

Although the pigs are kept in a sterile facility, the researchers performed additional tests for hidden infections. Everyone in the operating room must have certain vaccinations and have their blood tested.

After surgery, doctors carried Miller’s body in a wheelchair to the same ICU room where Montgomery recovered from a heart transplant five years earlier.

Next, a test was performed that was too severe for a living patient to endure. Your doctor will biopsy your kidneys every week and place the samples under a microscope to look for signs of rejection. Blood is monitored continuously, the spleen is examined, and nurses closely monitor that the body is properly maintained on the ventilator.

During the first few weeks, Griesemer checked laboratory test results and vital signs multiple times a day. “Well, I hope things are still good, but is today the day things start to change?”

And they ship biopsy samples to research partners across the country and as far away as France.

“Our staff doesn’t sleep much,” says nurse Elaina Weldon, who oversees the transplant study. But week after week, “everybody is seriously thinking about what more they can do and how far they can go.”

She knows first hand the great interest. New York University asked community groups and religious leaders before embarking on a study with donated bodies, which might sound “a little more sci-fi side of things.”

Instead, many wanted to know how soon life-environment studies would begin, but that would have to be decided by the Food and Drug Administration. Dozens wrote to Montgomery, eager to join.

Montgomery regularly called Miller Duffy and his wife for updates and invited them to New York University to meet the team. And as the deadline for the first month of research approached, he asked another question. “The research was going well, but could you keep his brother’s body for two months?”

This meant further postponement of plans for the memorial service, but Miller Duffy agreed. Her wish was to be present when her brother was finally taken off the ventilator.

Whatever happens next, this experiment changed Sue Duffy’s view of organ donation.

“When you go to heaven, you may not need all your organs,” she said. “I used to be a firm no, but now I am a firm yes.”