The world is now less than a year away from the next big thing. International Conference on Financing for Development It will be hosted by Spain. It is no exaggeration to say that the gap between the world’s development and climate challenges and the global policy and financial conditions needed to address them has widened since the last summit on the topic was held in Ethiopia in 2015. Many of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals are: Off track Scientists are now convinced that it is possible to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. extremely difficultThe number of people forcibly displaced by conflict, disasters and persecution is set to rise to more than 117 million by 2023, if not impossible. And outbreaks of zoonotic diseases like avian influenza continue. Reminder The next pandemic may not be as far away as we hope. Sadly, Two prominent development economistsEven in 2024, “the world is still burning.”

Rather than creating a new development consensus, these challenges are causing division, denial and delay. Prospects of stalemate Debates are ongoing between developed and developing countries over new climate finance targets – how much, what their composition should be and who should pay for it. Proposals for a modest carbon tax on global industries such as shipping to fund development and climate change responses have An unwilling union It is made up of developed and developing countries. Proposals from several member states include: Minimum tax on billionaires This year’s G20 summit in Brazil is likely to encounter similar resistance, and recent assessments suggest that as of mid-year, Less than one in five of the global funding needed to alleviate humanitarian suffering in 2024 has been made available.

The paradox is that while the collective impact of these challenges is felt globally, our partial and fragmented system of global governance means that the primary policy levers for addressing them remain at the national level. For developing countries, addressing poverty, inequality and climate change means making political deals at home and building institutions that can support economic growth, environmental and development goals. For developed countries, global challenges like trade, security, migration, technology and decarbonization require building political and national consensus that can advance long-term interests and manage big development policy trade-offs that go beyond the narrow calculations of transactional statecraft.

Nevertheless, international cooperation and external development finance (Official Development Assistance (ODA or “aid”), other public funds, philanthropic funds, and publicly mobilized private funds) still play an important role. Despite its shortcomings, aid, compared with other sources of finance, has been one of the most stable sources of financing for developing countries in times of crisis since the 1960s (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total net resource flows from OECD DAC countries to developing countries, 1960-2022 (constant 2022 US$ billion)

Source: OECD DAC (2020), 60 Years of ODA: Insights and Perspectives During the COVID-19 Crisis. Figures and deflators from 2019 onwards are provided by OECD DAC.

Aid has continued to grow substantially over the past few years, with ODA from OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors reaching 1.1%. Climb the record Following recent crises such as COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is projected to reach $224 billion in 2023. As a share of DAC donors’ total wealth, aid over the past two decades has increased by more than 50%, from 0.24% of gross national income in 2003 to 0.37% in 2023.

However, this is a far cry from the 0.7% ODA/GNI target first adopted by the UN more than 50 years ago. With just five Of the 31 DAC donors who will meet or exceed this target in 2023, 10% of net transfers to developing countries in 2022 fell to the lowest level Since the global financial crisis, outflows such as private debt repayments have exceeded inflows such as new development loans and subsidies, resulting in negative net transfers in 26 developing countries.

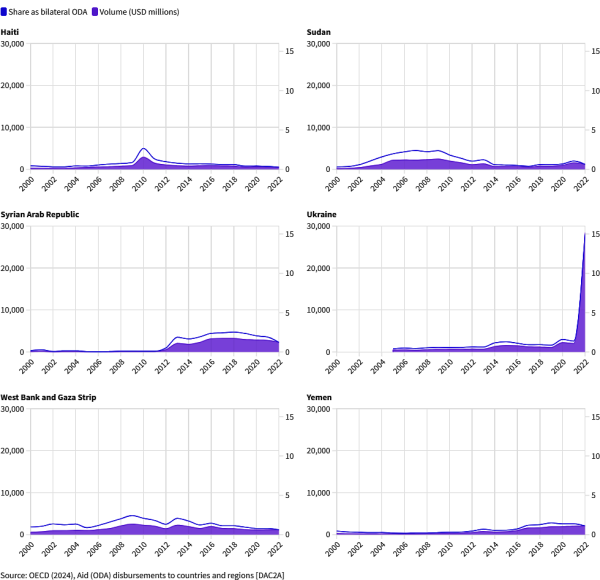

And there are natural questions about allocation: compare, for example, the disparity between the surge in ODA to Ukraine after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and aid to other long-term crises up until that point (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: DAC member states’ responses to selected crises and conflicts, 2000-2022

Source: OECD (2024)), Trends in Official Development Assistance in Times of Crisis. Note: This data only records up to 2022, so it doesn’t include humanitarian aid provided to Gaza or other crises since the start of the conflict in October 2023.

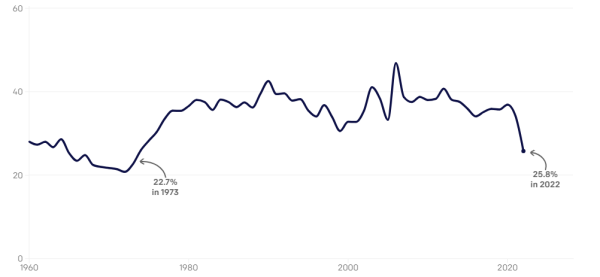

The share of aid from G7 countries and EU institutions to Africa, which contains countries with the highest rates of extreme poverty, fell to its lowest level in almost 50 years in 2022 as these donors cut bilateral aid or shifted funds to priorities such as supporting Ukraine and internally displaced people (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Percentage of ODA from G7 and EU institutions to Africa, 1960-2022

Source: One Campaign (2024), Share of G7 aid to Africa is lowest since 1970s

Some Western countries that have cut aid to Africa complain that China is playing too big a role in the continent’s development and beyond, but China is scaling back aid as it faces its own economic problems. Lending to Africa They are set to fall to a 20-year low in 2022, much of it for conservation purposes. more and more Unstable government bond portfolio.

False promises of billions to trillions of dollars made by Western countries to mobilize private development finance have not been delivered. According to some expertscertainly not. Leveraging “private sector tools” Instead of real financial efforts, they are trying to artificially inflate aid budgets. Meanwhile, these budgets are Being robbed and/or “renaming” it to meet supposedly “new and additional” climate finance commitments, imposing further costs on climate-vulnerable countries.

Increasing geopolitical competition makes global collective action problems such as global health scares and climate change even more challenging. The world’s development institutions are also increasingly fragmented, with developing countries prioritizing the role of the UN system (and establishing new UN agencies) where they hold a majority, while Western countries emphasize the primacy of institutions such as the G20 and international financial institutions. Substantial governance reforms of the latter are long overdue. Still difficult The geopolitical impasse makes any “grand deal” on issues such as aid effectiveness, climate finance and debt restructuring even more difficult.

The combined effect of all this is Loss of trust Tensions between the West and many countries in the Global South. But China is not automatically benefiting from this. China is also Increased monitoring It has been criticised for its hardline stance on debt and loan quality, and questions have been raised about its climate change obligations. A large, emissions-intensive economy.

If all this sounds bleak, unfortunately, the future doesn’t look so bright. The rise of far-right populists in Europe and a possible Trump victory in the US in November could bring new shockwaves. The whole EU and the US are More than two-thirds of the world’s ODA In 2023, a combined 16% cut in U.S. and European ODA (equivalent to the one-year cuts made in Australia by the Abbott government in 2015) would reduce global aid by about $27 billion. Multilateral and climate aid are likely to be key targets, along with aid for sexual and reproductive health and rights, and gender equality.

In the second part of this blog, I want to be less pessimistic and look at some concrete proposals to improve this situation and improve the prospects for effective development financing.

Disclosure

This study Gates FoundationOpinions expressed are the author’s own.