Sometimes it takes an unlikely friendship to change the world.

One such collaboration in American education began in the early 20th century, when Julius Rosenwald, an enormously successful retailer turned philanthropist, met notable educator Booker T. Washington. The two decided to work together, hoping to improve education for black students in the racially segregated South. Their collaboration led to the establishment of approximately 5,000 “Rosenwald Schools” in 15 southern and border states between 1917 and 1937.

By some accounts, this was a huge success.

These schools This caused a “rapid narrowing” The gap in academic achievement between white and black students in the South.

But a recently published book about the school says it was a “tipping point.”A better life for childrenAnother reason is that many of the school’s students went on to become active in the civil rights movement, which overturned racial segregation as official American policy. What’s Included John Lewis, a longtime U.S. congressman, and Medgar Evers, the NAACP field secretary who was assassinated in 1963.

Today, most of those schools have faded into history, with only around 500 remaining, in varying states of maintenance.

Georgia-born photographer Andrew Filer visited and photographed 105 surviving schools and spoke with people connected to the schools and their legacies to publish “A Better Life for Kids.” His book, published in 2021, is now the basis of a traveling exhibition.

These days, race and educational opportunity appear to remain problematically related. NAEP data consistently show that: A 30-Year Gap Black students perform worse than white students in areas such as math and reading in 12th grade. This difference is Often criticized About racial and economic segregation.

Perhaps that is why some observers are viewing the exhibition on Feyler’s past as Racial and educational disparities todayIn particular, they point out the lack of adequate resources for public schools and the current state of the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

So EdSurge caught up with Feiler and asked him what lessons he thinks the Rosenwald School can teach educators today.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

EdSurge: When and why did you decide to take on this project?

Andrew Feiler: I’ve been a serious photographer for most of my life, but about 12 years ago I started on a path to taking my work more seriously, and thankfully being taken more seriously, and I needed to figure out what my voice was as a photographer.

I’ve always been very involved in the civic life of my community, I’ve been very involved in nonprofits and the political world, and when I thought about my voice as a photographer, I found myself drawn to subjects that I care about in civic life.

And I First photo bookreleased in 2015, depicts an abandoned university campus. It exploits the emotional disconnect between familiar educational spaces: classrooms, hallways, locker rooms. But it also has the superficial feel of an abandoned place…

That body of work became about the importance of historically black colleges and universities and the importance of education as a gateway to the American middle class.

And then, as I was trying to figure out what to do next, I was having lunch with an African-American preservationist, and she was the first person to tell me about the Rosenwald School, and it just blew my mind.

I am a fifth-generation Georgian Jew. I have been a civic activist my whole life. The pillars of Rosenwald School’s history — the South, education, civics, and progressivism — are pillars of my life. It is impossible to have never heard of Rosenwald School.

So I went home and Googled it, and discovered that while there were plenty of academic books on the subject, there was no comprehensive photographic account of the program. So I decided to do just that. Over the next three and a half years, I drove 25,000 miles through all 15 states covered by the program. Of the original 4,978 schools, only about 500 remain. Of those, about half, 105 or so, were restored, and the result is this book and this traveling exhibit.

Can I introduce the characters?

Yes, please introduce me.

The story centers around two men.

Julius Rosenwald was born to Jewish immigrants who fled religious persecution in Germany. He grew up in Springfield, Illinois, and lived across the street from Abraham Lincoln. He rose to become president of Sears, Roebuck & Company, and helped grow Sears into the world’s largest retailer at the time with innovative policies such as “Satisfaction Guaranteed or Your Money Back” and became one of the oldest and greatest philanthropists in American history.

And his cause was what would later become known as “civil rights.”

Booker T. Washington was born a slave in Virginia, attended Hampton University and became an educator. He was originally the founder of Tuskegee University, a historically black college in Alabama.

The two met in 1911.

Remember, 1911 was before the Great Migration. [the period between the 1910s and the 1970s when millions of Black people poured out of the South and moved to the North, Midwest and West fleeing racial violence and seeking opportunity].

Ninety percent of African Americans live in the South, and the public schools that serve African Americans are mostly shacks and funded at a fraction of the resources given to public schools for white children.

And that was the need and the environment that they found. And so, these two men fell in love with each other, formed a partnership, worked together, and in 1912 created the program that became known as the Rosenwald Schools. And over a 25-year period, from 1912 to 1937, they built 4,978 schools in 15 states in the South and along the border, and the results were transformative.

What were your impressions after visiting many of the remaining schools?

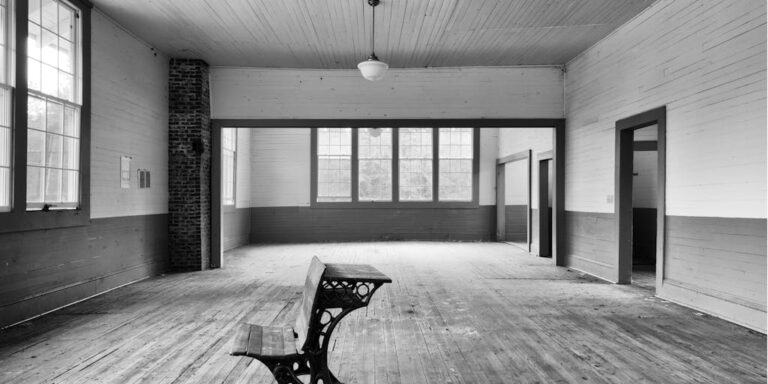

Yes, there is austere beauty in the buildings. Their architecture is vernacular and specific to the site. I find them beautiful whether restored or ostensibly abandoned.

But I think there is another important factor.

I knew this was an amazing story. I didn’t know, from the beginning, how to tell it visually. So I started by shooting the exteriors of these buildings. Schools with one teacher, schools with two teachers, schools with three teachers. These are small buildings. By the end of the show, they had one-story, two-story, three-story red brick buildings.

There’s a fascinating architectural story, but when I learned that only 10 percent of the school remains, and of that, only half has been restored, I realized that the need for historic preservation is a very important part of the story, because these spaces, these places, are central to the history and memory of the community. [and when] When we lose these places and spaces, we lose a part of our American soul.

And then when I realized the preservation story was important, I needed to go in, and all of a sudden I needed permission, and that’s when I met some incredible people — former students, former teachers, preservationists, civic leaders — and brought their connections to the broader story of the Rosenwald School into this story through the portraits.

To what extent does the timing of your project depend on the recent strong desire to focus on preserving Black history, and to what extent does that explain why it resonates now?

I want to say a few things about the Rosenwald School program. First, the Rosenwald School was one of the most transformative developments in America in the first half of the 20th century. The school dramatically changed the African-American experience, which in turn dramatically changed the American experience.

Two economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago conducted five surveys. Rosenwald School Studyand their data shows that before the Rosenwald Schools, the educational gap between blacks and whites in the South remained large and persistent. That gap narrowed rapidly between World War I and World War II, and the biggest driving force behind that achievement was the growth of all schools. Moreover, many of the leaders and foot soldiers of the civil rights movement came from these schools. Medgar Evers, Maya Angelou, multiple members of the Little Rock Nine who attended Little Rock Central High School, and Congressman John Lewis, who wrote this wonderful introduction to my book, all came from Rosenwald Schools, and the results of this program have been transformative.

But to go back to the core of your question, I think what makes this story resonate today is that we live in a divided America, and the issues, especially those related to race, often feel incredibly intractable.

In 1912, Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington overcame racial, religious and regional divides in the United States at a time of severe racial segregation and Jim Crow laws, and fundamentally changed the country for the better. I think the core of this story speaks to anyone today who is a force for social change in America, and that individual actions still matter, and individual actions change the world.

So looking at your overall recent projects – this book and another one about Morris Brown University that you mentioned, “No Gender, No Race, No Color” – has anything specifically changed the way you think about education?

Through this work, I have come to appreciate the role that education has played throughout American history.

The first tax-funded school in America was founded in Massachusetts in 1644, 380 years ago. And it shows us the early commitment to education and Land-Grant University ActThese include the HBCUs that were established in 1862 and provide funding for colleges and universities across the United States; the HBCUs that were established primarily in the decades following the Civil War; the Rosenwald Schools of the early 20th century; and the education provisions of the GI Bill that transformed America from a relatively poor country to a relatively wealthy one. [and] Brown v. Board of EducationOne of the high points of the civil rights movement.

What are we talking about today? Cheap college tuition, book bans, restrictive curriculum, and more.

We have a 380-year tradition that education has been the foundation of the American Dream, the gateway to the American middle class, and today that tradition is in danger, and I think we need to understand and protect the importance of that tradition in our country.

Are there lessons educators can learn from this work?

I think what I just said is exactly in the spirit of what you’re asking. I mean, the level of division that exists across the country right now is alarming. I think it’s important for us as Americans to look back at history and how we’ve come together to make America a better place. The relationship between Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington is one of the earliest collaborations between blacks and Jews in the movement that would later become known as “civil rights.” Their collaboration, working together, and friendship is a model for how we as individuals can create change in our culture. They go beyond the racial divide. They go beyond the religious divide. They go beyond the divide to reach out to the broader areas where divisions remain in our culture even today.

They have risen above their divisions and are bringing change to our country. I believe this is a model for all of us to remember. We are the change we seek. We have the power to create change, and we need to follow in the footsteps of this story and remake our country for all of us.