Brazilian nutritionist Carlos Monteiro coined the term “ultra-processed foods” 15 years ago and established a “new paradigm” for evaluating the impact of diet on health.

Monteiro noticed that Brazilian families were spending less on sugar and oil, yet obesity rates were rising — a contradiction he said could be explained by the increased consumption of highly processed foods, with added preservatives and flavors, and nutrients removed or added.

But health authorities and food companies resisted the link, Monteiro told the Financial Times.[These are] People who have spent their whole lives thinking that the only thing that links diet to health is the nutritional content of food…food is more than nutrients.”

Monteiro’s food classification system, “Nova,” assessed not only the nutritional content of foods but also the journey they took to our plates. This system laid the foundation for 20 years of scientific research examining the association between UPF intake and obesity, cancer, and diabetes.

According to the UPF research, these processes can create foods — from snack bars to breakfast cereals to prepared meals — that encourage overeating while leaving eaters undernourished. For example, a recipe might contain levels of carbohydrates and fats that stimulate the brain’s reward system, so you need to ingest more to maintain the pleasure of eating.

In 2019, American metabolic scientist Kevin Hall conducted a randomized study comparing people who ate whole foods with those who followed the UPF diet over a two-week period. Hall found that those who ate ultra-processed foods ate about 500 more calories per day, more fat and carbohydrates, and less protein, which led to weight gain.

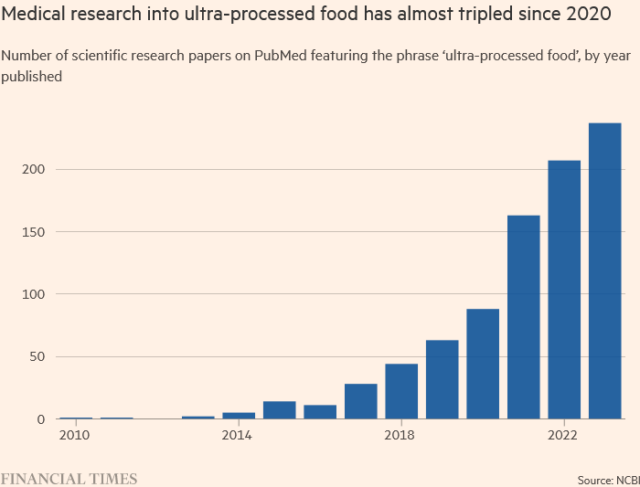

Growing concerns about the health effects of UPFs have reshaped the debate on food and public health, spawning books, policy campaigns, and academic papers. And they present the most concrete challenge yet to the highly profitable food industry business model.

The industry has responded with a ferocious opposition, using some of the same lobbying techniques it used to fight the labeling and taxation of high-calorie “junk foods” — spending billions of yen to influence policy makers.

A Financial Times analysis of U.S. lobbying data from the nonprofit Open Secrets found that food and soft drink companies are set to spend $106 million on lobbying in 2023, nearly double the amount spent by the tobacco and alcohol industries combined. Spending last year was up 21% over 2020, with the increase driven mainly by food processing and sugar lobbying.

Following the tactics employed by tobacco companies, the food industry has tried to circumvent regulation by casting doubt on the work of scientists like Monteiro.

“The strategies used by the food industry are denial, blame and delay,” says Barry Smith, director of the Institute of Philosophy, University of London, and a corporate consultant on multisensory experiences in food and drink.

So far, the strategy has been successful: A handful of countries, including Belgium, Israel, and Brazil, currently mention the UPF in their dietary guidelines. But as the weight of evidence on the UPF grows, public health experts say the only question now is whether or not it will be reflected in regulations.

“The science is consensus,” says Jean Adams, professor of dietary public health at the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge, “but the question is how to interpret that and make policies where people are unsure.”