As a participant in the Amazon Associates affiliate program, Upworthy may earn revenue from purchases linked in this post, at no additional cost to you.

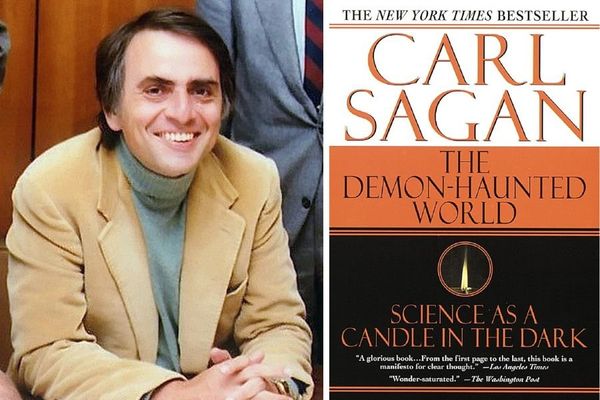

Cosmologist and science educator Carl Sagan gained fame in pop culture as host of the television show Cosmos and author of the book The Laws of the Universe. 12 or more books Bridging the gap between the scientific complexity of the world and the people who live in it. Intelligent and eloquent, he knew how to make science accessible to the general public and always advocated a healthy skepticism and the scientific method in searching for answers to questions about our world.

But Sagan also had a keen understanding of the broad range of human experience, which helped make him a beloved communicator. In addition to science, he wrote about peace, justice and kindness. Rather than shunning spirituality, as some skeptics do, he said science is a “profound wellspring of spirituality.” He acknowledged that there is a great deal we don’t know, but he was adamant in defending what we do know.

Now, here’s a quote from Sagan’s 1995 book: “A Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Light in the Darkness” People talk about his uncanny ability to peer into the future. Of course, his prophecies aren’t the result of supernatural means, but rather his powers of observation and understanding of human nature. Still, it’s pretty creepy.

He wrote:

“I have a vision of what the America of my children and grandchildren will be like: an America dominated by a service and information economy, with most of our manufacturing exported to other countries, our technological marvels in the hands of only a few, no one to represent the public interest able to grasp the problems, our people losing their ability to set their own agenda or to educate those in power, our critical fading, our inability to distinguish between comfort and truth, and a slide back into superstition and darkness, almost without our realizing it.

And nowhere is the dumbing down of America more evident than in the gradual decline of substantive content in our hugely influential media, shrinking 30-second audio clips to 10 seconds or less, giving way to substandard programming, presentations that promote pseudoscience, superstition, and, above all, the celebration of ignorance.”

In an era when the least qualified people are increasingly ascending to the highest positions of power, when people flock to heretical voices that defy the broad scientific consensus on everything from climate change to public health, and when blips on social media increasingly fuel fringe opinions lacking nuance or complexity, his words seem truly prophetic.

And what’s most frustrating is that those who get caught up in bogus conspiracy theories or take extreme positions based on illogical rhetoric are often unaware of their own ignorance. They are Critical thinkers, They are People who are knowledgeable precisely because they question authority (which is different from what Sagan calls “the ability to knowledgeably question authority”).

“When we become complacent and uncritical, when we confuse hope with fact, we slip into pseudoscience and superstition,” Sagan writes. We’ve seen this play out in the United States during the pandemic. We see it every day on both sides of the political aisle, and we witness it especially in our online social debates. One thing Sagan didn’t foresee: that in today’s world, ignorance, pseudoscience, and superstition are rewarded by the algorithms that determine what we see in our social media feeds, creating a vicious cycle that sometimes seems irreversible.

But Sagan also offered a hopeful warning that those who fall prey to peddlers of “alternative facts” for their own profit are simply human beings with the same desire to understand the world we all share. He warned against being critical without kindness, and to remember that being human does not come with an instruction manual or an innate understanding of how everything works.

“When skepticism is applied to matters of public concern, it tends to ignore, whether dismissive, condescending, or deluded, the fact that proponents of superstition and pseudoscience are human beings with real feelings and, like skeptics, are trying to understand how the world works and what our role in it is,” he wrote. “Their motivations are often aligned with science. If their cultures have not given them all the tools they need to pursue this great quest, let us temper our criticism with kindness. None of us are fully equipped.”

Distinguishing between truth and falsehood, fact and fiction, science and pseudoscience is not always easy, but so is the challenge of educating the public to hone that ability. Following Sagan’s lead, we can approach education not only with rigorous scientific standards, but also with curiosity and wonder, kindness and humility. If Sagan was right about the direction America was heading 30 years ago, he may have been right about the need to understand what led us there and the tools we need to steer the ship in the right direction.

Sagan’s “A Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Light in the Darkness”here.