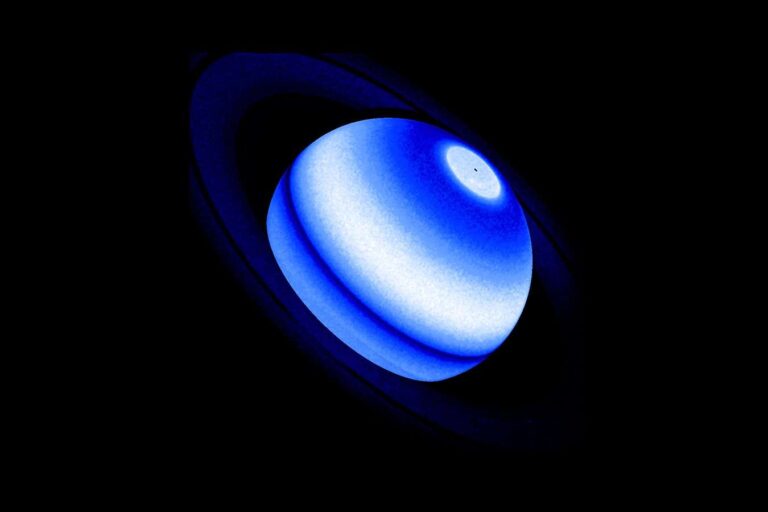

Composite image showing hydrogen on Saturn

NASA, ESA, Lotfi Ben-Jaffel (IAP & LPL)

Saturn’s rings keep the earth hot. Four decades of observations have shown that particles from the ring rain down into the atmosphere, where they collide with and heat the hydrogen.

Lotfi Ben Jaffel The Paris Institute for Astrophysics and his colleagues have conducted two Voyager probes that passed Saturn in 1980 and 1981, the International Ultraviolet probe, a space telescope that operated from 1978 to 1996, and the Cassini spacecraft. We used archival data to make this discovery. A spacecraft that orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017. However, all these observations were made with different types of instruments and therefore could not be directly compared.

To fix that, Ben Jaffel and his team used the Hubble Space Telescope to make new observations of Saturn. All archival measurements were then adjusted so that the UV brightness matched what Hubble measured, allowing the light spectrum from each spacecraft to be compared to others.

“When everything was calibrated, we could clearly see that the spectra were consistent across all missions. statement“It was a real surprise to me. I plotted the various light distribution data together and wow, it turns out they’re the same.”

All measurements showed extra ultraviolet radiation coming from Saturn’s lower latitudes below the rings. We know that the rings are slowly collapsing under the influence of solar radiation, particles, micrometeorites, and electromagnetic fields, but the planet itself seems to be affected by that collapse as well. When tiny pieces of ice rain down from the rings onto the planet, they heat the upper atmosphere, causing excess ultraviolet brightness.

But researchers have also discovered a mystery. These same low latitudes appear to have inexplicably hot hydrogen. Some of this hydrogen could come from the rings and Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, plus chemical reactions and mixing in the atmosphere, plus despite all the observations over the years, we know nothing about Saturn’s interior. We don’t know enough. surely.

topic: