Eastern Ukraine

CNN

—

His forearms bulged with the effort of holding onto the straining leash of a slobbering dog. The creature’s muffled grunts could be felt as much as heard – like the growls of a souped-up truck.

Which was fitting, given that his owner’s call sign is Brabus – after the German firm specializing in bulking out luxury vehicles with engineering testosterone.

“Come,” Brabus grunted as he was towed back into a roadside building for our clandestine meeting with some of his special operations team.

They’re part of a shadowy tapestry of units falling under various Ukrainian intelligence organizations. They operate in the crepuscular landscapes in the war against Russian occupation on and beyond the front lines.

Other groups run by Ukrainian intelligence include the Russian Volunteer Force and Freedom for Russia Legion, formed of Russian citizens fighting to rid their homelands of President Vladimir Putin, which are currently carrying out raids inside Russia from Ukraine.

But Brabus and his group are entirely homegrown. Former soldiers with specialist skills, they coalesced around an ex-officer from the Ukrainian forces in the first days of Russia’s invasion last year.

“At the beginning of the war there was a big role for small groups who could fight covertly against the Russians. Because Kyiv region, Chernihiv region, Sumy region are forested areas. So, the role of small groups was important and grew fast,” said Brabus’ boss from inside a camouflage balaclava.

In those early days and weeks, small bands of men in pickups, armed with anti-tank rockets like NATO-supplied NLAW and Javelins, ambushed, trapped, and picked off invading Russian columns down main arteries running in from the north.

Bold, fast-moving and insanely brave, they preyed on Russia’s military Leviathan – eventually, north of Kyiv and Sumy, stopping the invasion in its tracks.

While they were scratched together into “reconnaissance units” back then, some have since been absorbed into the formal army structures.

But all have clung to the freewheeling, partisan-style of warfare with higher risks but greater autonomy.

Those who’ve survived – and many have not – are now often set to work at tactical tasks aiming for strategic effect. Crudely put: killing Russian officers to collapse Russian morale.

Brabus agreed to share, to a degree, the story of one such operation.

In early March, when eastern Ukraine was powdered with snow on top of frozen ground, Brabus said he and his team snuck in through skeletal woodlands to a regular army post on the front line south of Bakhmut.

He said that signals intelligence suggested that Russian units were being swapped over. This meant there would be more officers present than normal and – better still – the incoming leadership would be naive and prone to fatal error.

Illustrating the story with video footage recorded at the time, he explained that his group was immediately caught up in a ferocious firefight with incoming Russian paratroopers new to this front.

“They got it back from us all guns blazing,” he said, his eyes kindled with pleasure at the memory of the Ukrainian fire.

Two videos glow in a metallic orange. Trees show up silver-black, while living creatures, such as men, appear as intense and moving white dots. These are video recordings from his thermal sniper sight while Brabus was at work.

The videos are silent, but more eerie for it. Somehow one can see the white figures are bent double, crouching perhaps. One can imagine these Russian soldiers scanning the darkness, searching for threats, their nerves screeching at every crunch of snow and crack of twig underfoot.

The red cross-hairs of his thermal sight settle on one of the figures. The cross leaps with the recoil of the rifle, and the little ghost crumbles to the ground. The red cross slides right, leaps again, another crumple.

“On the left were their (the Russians) dugouts and trenches from where they could see our positions. We eliminated, or rather I eliminated, paratroopers from the left flank,” Brabus explains in the clinical language characteristic of military reports.

His unit’s task, though, wasn’t to help entrenched troops fighting in the “meat grinder” of the Bakhmut front, he said. Its prey was the Russian paratroop leadership.

“We are a diversionary reconnaissance group. We did the reconnaissance, we got the intel, we prepared the operation,” he said.

“How many Russians did you kill that night?” we ask.

“Seven,” says Brabus.

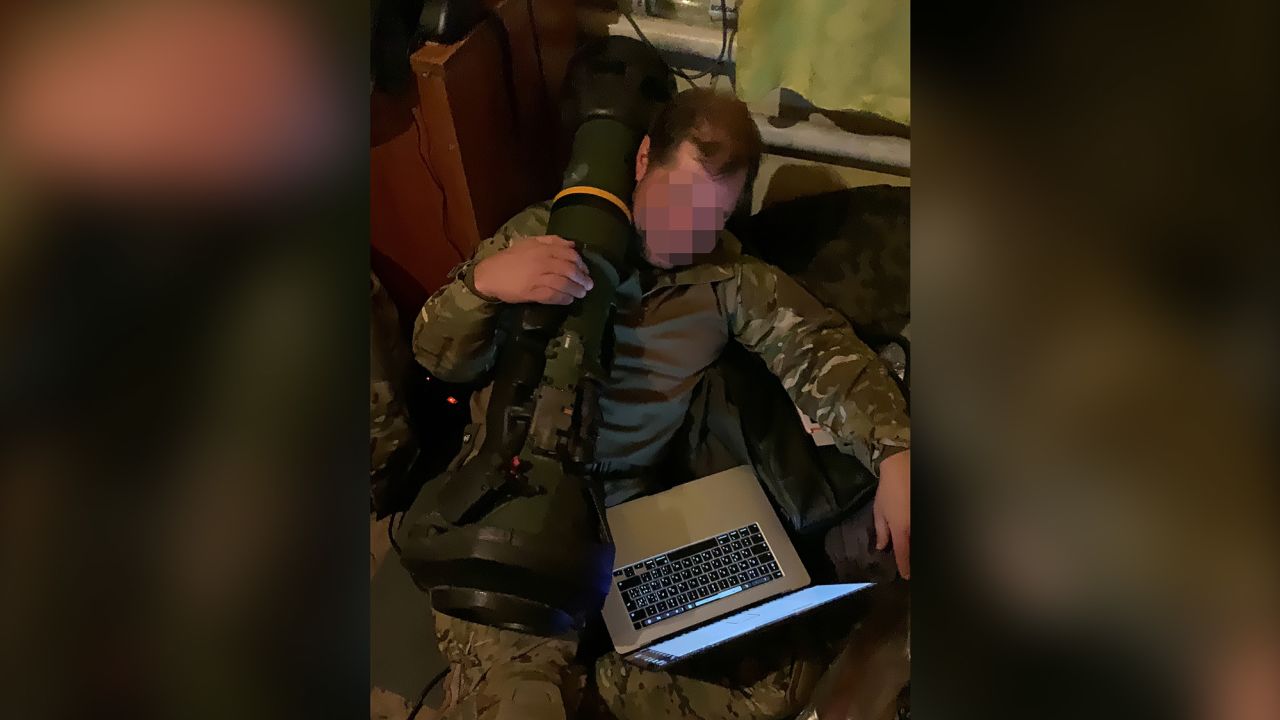

He’s more animated when discussing the weapon that sits behind him, like another enormous pet, in the cafe where we meet. It’s a modified 12.7 Soviet-era heavy machine gun that a local armorer has fitted with a fat, bulging suppressor (silencer).

Shooting from an underground hide with a range, he claimed, of two kilometers (a little over a mile), this weapon is almost silent, Brabus says.

In May, he was in a dugout overlooking a junction of trees close to Bakhmut. Another video shows him take aim then pull his face from the weapon as he lets rip, sending high explosive supersonic bullets, thicker than a man’s thumb, into clusters of the enemy’s forces.

A drone operator two kilometers back from Bakhmut, is watching where the bullets strike and calling in adjustments to his aim. The video captures his voice crackling over the radio, “spot on, perfect.”

“With this,” Brabus explains. “I kill a lot of Russians, a lot.”

Ukraine is now advancing south of Bakhmut along a salient about four miles deep, pushing Russian forces back.

And, as its counteroffensive to reclaim territory captured by Russia gets under way, Ukrainian forces are fighting in ever greater numbers along an east-west front between Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia.

Since Brabus and his group were in Bakhmut, there appears to have been growing anarchy among Russian commanders. Russian mercenary leader Yevgeny Prighozhin’s Wagner company, who were holding the city, arrested and beat up the commander of the neighboring Russian 72nd Brigade.

They released a recording of the injured man “confessing” to being drunk and opening fire on them. He was beaten up, and released.

He’s now accused Wagner and its mercenaries, who already have a well-earned reputation for murder and summary execution, of attacking this men.

It’s this kind of chaos in the ranks of the enemy that Ukraine most wants, indeed needs, to see.

Brabus is happy to do his part in trying to create it.