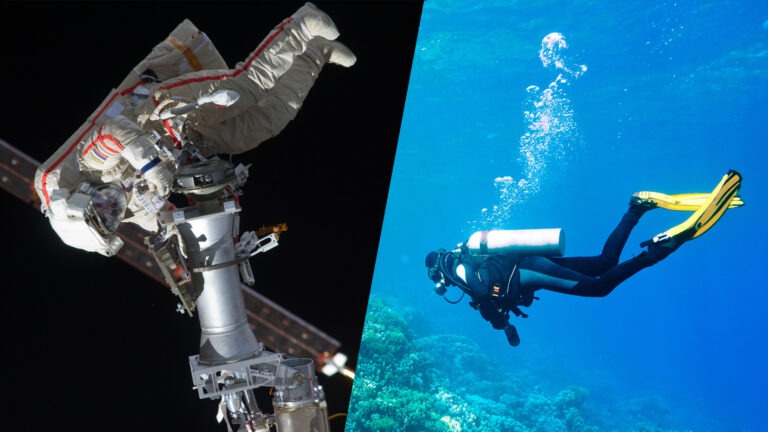

Space and the open sea. On the surface, it seems like there couldn’t be more contrasting places. But on the contrary, the two are more closely linked than you might think. And anyone who’s been to the furthest reaches of both can attest to that fact, because there are striking similarities between the type of training and experience required, and both environments.

Just ask aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut Nicole Stott, who spent 104 days in space on the space station and space shuttle and spent a lot of time underwater, partly in preparation for space travel but also for fun and education now that she spends most of her time on Earth.

PADI (Association of Professional Diving Instructors) certified divers agree that the ocean and space have a lot in common. After all, both are difficult to access, extremely dangerous, require ultra-specialized equipment to navigate, and are harsh environments for humans to inhabit. This turns out to be quite convenient, because while it may be difficult to simulate zero gravity and the vacuum of space, the ocean offers a training ground for a truly analog and impressive simulation.

In fact, astronauts have to spend time underwater before they can even think about traveling outside Earth’s atmosphere aboard a shuttle, and there’s even a training center dedicated to that purpose: the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston, which trains astronauts for spacewalk training. Inside, you’ll find one of the world’s largest indoor swimming pools, measuring 202 feet long, 102 feet wide, 40 feet deep and holding 6.2 million gallons of water, as well as replicas of parts of the International Space Station and other man-made structures in space.

In this pool, astronauts don the 300-pound suits and lots of other gear to make them neutrally buoyant, and dive underwater surrounded by a team of support divers to learn and feel what it’s like to operate and move in space. In fact, Stott says, this is the closest sensation we can get on Earth to simulating space travel (minus the resistance and weight you feel underwater).

After all, in both places you’re floating – underwater because you’re buoyant, in space because there’s no gravity – and in both places you can’t just finish the day, throw off your helmet and breathing apparatus, and walk home.

That’s why Stott and his team also train at Aquarius Lab, an underwater habitat and Aquanaut basecamp 60 feet below the surface off the Florida Keys. Stott spent 18 days underwater, where “you’re in a true extreme environment,” he explains. It’s just like being in space, albeit at a much higher pressure. But being at that depth simulates the movement and teamwork needed outside Earth’s atmosphere, as well as the sense of isolation and independence.

“You can’t just run away,” Stott explains. If you dive deep enough, your body and blood become too saturated with nitrogen to quickly surface if you get into trouble. Once on the surface, the excess nitrogen can cause bubbles in your blood and lungs, which can cause serious disability, decompression sickness, and even death from arterial gas embolism. At the depths of Aquarius, you can become saturated after just 60 minutes of diving, Stott explains.

Of course, you could take refuge in a relatively safe “indoor” environment, just like you would in a spacecraft, but in either location, “if something goes wrong, you and your crew have to figure out how to make it a safe configuration, including keeping the crew safe.”

Everything about spaceflight is similar to spaceflight, she continues: how to communicate, how to interact with the crew and mission control team, how to live in tight spaces, how to use specialized equipment, how to handle emergencies, etc. Except on the one hand you’re surrounded by water and under pressure, and on the other you’re dealing with the deadly vacuum of space.

“This is the ultimate analogy for the extreme conditions of space,” Stott says. This is even tougher than other training astronauts have to endure, such as cold and wilderness survival. But in those situations, she explains, they know help is just a satellite phone away. Whether deep in space or deep underwater, it’s all about their own survival, teamwork, and knowing how to manage stress in high-risk environments. “It’s a totally different psychological experience,” Stott adds.

Diving qualifications aren’t required for aspiring astronauts, either professionally or as space tourists, but if you don’t already have experience diving and your astronaut application is accepted, you’ll likely gain the qualifications and experience quickly, Stott said.

For those who prefer to prepare in advance or want to experience what space is like on Earth, Stott is happy to show you. In fact, she just finished the second Island Astronaut Camp in the Maldives, partnering with PADI and COMO Maalifushi. Kids snorkeled together, built bottle rockets, designed space suits, and learned the importance of acting as crew members, not passengers, whether they were heading into space, staying firmly rooted to the ground, or exploring underwater environments. This is just one of the ways she connects the space curious with the serious space enthusiast through her Space for A Better World and Space for Art Foundations.

“It’s amazing that spending time underwater, living and working in inner space, can prepare you for life and work in space,” Stott says. If you want to experience what space is like, head underwater.