newYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Hundreds of people have sailed through my life during my 30 years at The Washington Post, but none have matched the impact Bob Andrews had on me.

Bob died of Parkinson’s disease on December 2, silencing a man hundreds of others could not silence, from the jungles of Southeast Asia to the mountains of Afghanistan. he was 85 years old.

Only two years ago, outside my gym on the western edge of Washington, from the moment he approached me behind me, I felt a force field around him. He was a true spy who fought in the wilderness, jumped out of planes, wrote novels and military textbooks, made business deals, knew presidents and chieftains, counseled former astronauts, and terrorized bad guys.

GOP Bill Pushes Veterans Health Care Plans onto House Representatives, Reminds Veterans

Bob has published three spy novels, including one published in 1993 titled Death in the Promised Land. It was followed by three mysteries built around a pair of Washington DC homicide detectives. bottom. A contemporary exploration of the unanswered questions surrounding the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Bob Andrews was awarded numerous medals for his country, including the Bronze Star and the United States Army Medal of Merit.

Bob also authored a dissertation on riot control operations in Vietnam, which was published as “The Village War,” a text used at the National War College in Washington.

“My father had a great life,” said daughter Elizabeth modestly. Bob was a character in Daniel Silva’s thriller.

In our conversation Bob never mentioned his numerous embellishments, perhaps because it took too long. He earned his Bronze His Star, Air Medal, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Company Infantry Badge, Master Paratrooper Badge, and Special Forces Tab. The Republic of Vietnam awarded him Gallantry Cross First Class. He received the 2007 Department of Defense Award for Outstanding Public Service and the United States Army’s Medal for Outstanding Civil Service.

My reporting instinct flashed, “Results man…accept!” When this total stranger offered to ride me in the powered-up Mini Cooper convertible I was admiring outside the gym. “Get on. Let’s go ride. Do you want to drive?”

I accepted. and left.

He learns that he once lived in a hazy underworld between the sophisticated Washington noggins who formulated policy and the field experts who wiped out their enemies.

“His breadth of national security experience was rare.” He knew that side of the war.”

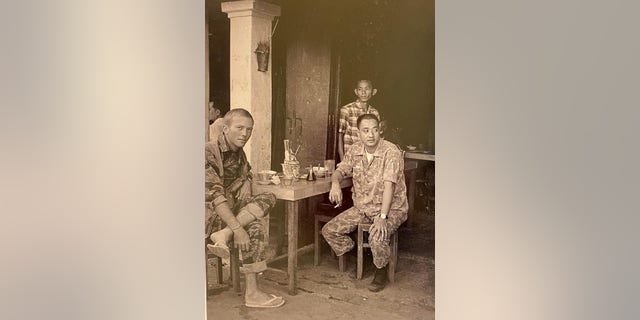

Bob trained as an engineer and graduated from the University of Florida before enlisting as a second lieutenant in the Army. He flew into covert operations during his first tour to Vietnam as part of a force conducting long-range reconnaissance missions along the borders of Laos and Cambodia and other unconventional operations in Southeast Asia.

Director Spike Lee has agreed to buy the rights to Death in the Promised Land, a contemporary exploration of the questions surrounding the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

(Vittorio Zunino Cerotto/Getty Images for Kering)

His second tour was with the Green Berets. Before leaving the military after 20 years, he earned a master’s degree in Asian Studies from Northeastern Missouri State University, since it was renamed Truman State University, and served in the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg.

After turning 20, he went to the CIA, where he worked on operations in Southeast Asia before moving into legislative work. The CIA has ceded its longtime position as military adviser to Democratic Senator John Glenn of Ohio.

On 9/11, he was summoned back to work when Bush appointed him Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations.

Bob served in various roles for the Pentagon, including counterintelligence, special operations, and special assistant to Gelen. His experience in Vietnam taught him the limits of technology to tribal loyalty when he directed the 5th Special Forces Group into Afghanistan.

Bob Andrews traveled the world for his country to fight America’s enemies and advise US leaders.

He grew up in an orderly and civilized society, but quickly adapted to chaos when he needed work.

Longtime friend and colleague Shepard Hill said, “He could talk about PhDs and high-level things at Harvard.” “He was also the only man at the mad table of policy who jumped out of planes with a gun, shot people and crawled through the jungle. I was able to bring the details into the discussion..”

Bob had a hard time. He has run multiple marathons. He was in one of his workouts in 1978 when Haynes at his DC point was hit by a truck, shattering his pelvis and damaging his back. However, after he recovered, he ran several more marathons.

On a Friday in August, when he ordered the closure of a critical missile parts factory for violating security regulations, he didn’t blink and surprised Pentagon executives and corporate moguls, Jeren said. The problem was fixed by the following Monday.

“Bob was reading a news report about mold growing in the barracks in Fort Sill, Oklahoma,” Jelen said. “Bob said, ‘Let’s get a plane and go there. Soldiers and their families need to meet with the Secretary of War in person.'”

Geren said Bob taught him important management lessons.

“Bob was reading a news report about mold growing in the barracks in Fort Sill, Oklahoma,” Jelen said. “Bob said, ‘Let’s get a plane and go there. Soldiers and their families need to meet with the Secretary of War in person.'”

Instead of following the normal procedure of following the chain of command and ordering investigations from top to bottom, Bob advised Gelen to start at the bottom, where the soldiers live, when it comes to the health and welfare of the soldiers.

“I called the chief of staff and requested a flight and flew to Sil the next morning,” Gelen said. “We met with the soldiers living in the barracks, the commander saw the mold first hand and promised to fix the problem.”

Bob was an extrovert. “He loved talking to people,” Elizabeth said. “He made friends with everyone from the bartender at Martin’s Tavern to the homeless man who lived in Solomon’s Alley. He thought everyone had a story and loved to hear it. ”

Bob was a patriot. “When I was a kid, I used to ride in the back seat of a station wagon, where my dad would always lead us through songs like ‘God Bless America’ and ‘This Land Is Your Land. ‘ said daughter Elizabeth.

Click here to get the opinion newsletter

Bob was humble. “He sat and listened in meetings,” Gelen said. “Sometimes I comment. But when it was over, he went to his boss and told him this is what we should do.”

One of our last lunches was at Martin’s Tavern on August 6, 2021. A few weeks before the conference came gloomy messages about the ongoing Parkinson’s disease.

Longtime friend and colleague Shepard Hill said, “He could talk about PhDs and high-level things at Harvard.” “He was also the only man at the mad table of policy who jumped out of planes with a gun, shot people and crawled through the jungle. We were able to bring the details into the discussion.”

That summer day, Bob was understandably distracted. Only after meeting him did he realize his vulnerability. I was terribly sad, but proud to have been with such an accomplished man during the most sensitive time of his life. I continued to take it, but the frequency of exchanges decreased.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“Parkinson’s is recovering a bit, but not without fights,” he wrote. I’m in prayer, great, Bob.”

Our last email exchange was on November 5, 2021, where I asked Bob how he was feeling and told him he was in my prayers. Here is his reply: “SAS, Tom. (Still.Above.Sod.) Stolen from FB Morse. Rest less and less pleasant, but always brightened by incoming traffic. Thank you, Bob.”

No thanks Bob.

Click here to read more about Thomas Heath