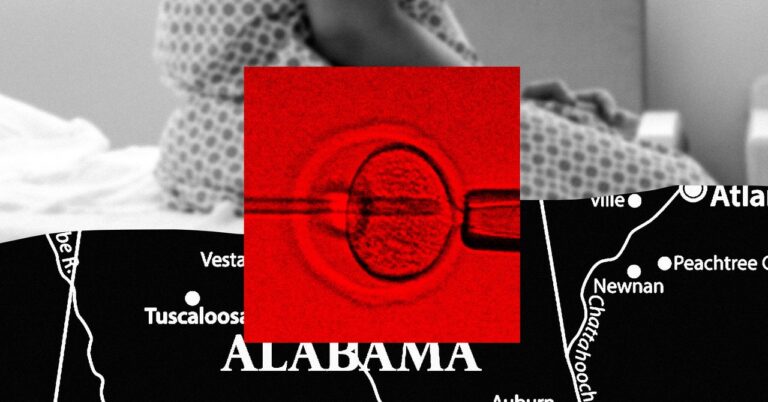

In October, Melissa started an IVF cycle. The Birmingham, Alabama, resident’s journey to fertility was not only difficult but harrowing. Earlier that year, she nearly died from blood loss during a procedure to resolve a second-trimester miscarriage. When the IVF process yielded her only one viable embryo, she froze it and started another cycle a few months later. “It’s very easy to lose an embryo,” she says. “This is a very delicate process.”

Melissa has a daughter born at a young age, and IVF is her best and last chance to expand her family. All that is now on hold after the Alabama Supreme Court ruled last week that a fetus is a child.

WIRED spoke with three women directly affected by the Alabama Supreme Court’s Feb. 16 decision. rulingThe paper states that an embryo “is a fetus without exception based on stage of development, physical location, or other incidental characteristics.” Fearing legal liability given the broad scope of the term, some of the state’s most prominent IVF providers, including the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama Fertility, and Mobile Reproductive Health Center is temporarily suspended. That means patients like Melissa, who goes by pseudonyms due to the sensitivity of the topic, are stuck and, in some cases, are running out of options.

“We’re losing time quickly,” says Melissa. The 37-year-old has an autoimmune disease and needs to plan her IVF cycle. Her ovarian reserve is low enough that her doctors say she has a month, maybe two months, before trying again. If this sentence lasts much longer, she may never have another chance.

During IVF, patients take hormone-stimulating drugs that stimulate the release of mature eggs from the ovaries. The eggs are then collected with a small needle and fertilized with sperm in a laboratory to form an embryo. Although a successful IVF cycle may result in multiple embryos, the doctor usually implants only one or two embryos into the uterus at a time. Success is not guaranteed.Approximately 1 in 3 embryo transfers result Pregnant.

That makes Melissa’s situation particularly urgent. She has no guarantee that her one embryo will lead to childbirth. But the ruling disrupted the woman’s life at every stage of her treatment.

Lochrane Chase started IVF in August after trying to conceive for nearly a year and undergoing less invasive fertility treatments such as ovarian stimulation. The 36-year-old from Birmingham was able to cryopreserve more than 20 embryos, some of which appeared to be viable after genetic testing. He became pregnant after an embryo transfer in October, but Lochrane miscarried a few days later. “It was the saddest time I’ve ever been in my life,” she says. She tried again in December. She miscarried again.

Before her next scheduled transfer in January, doctors noticed fluid in her uterine lining. Lochrane underwent surgery in mid-February to address the issue, and on March 18 she scheduled another embryo transfer. Despite the uncertainty caused by her sentence, she started taking the necessary hormones anyway, hoping the situation would be resolved by then. Otherwise, her medicine will be wasted and she will not be able to move forward.