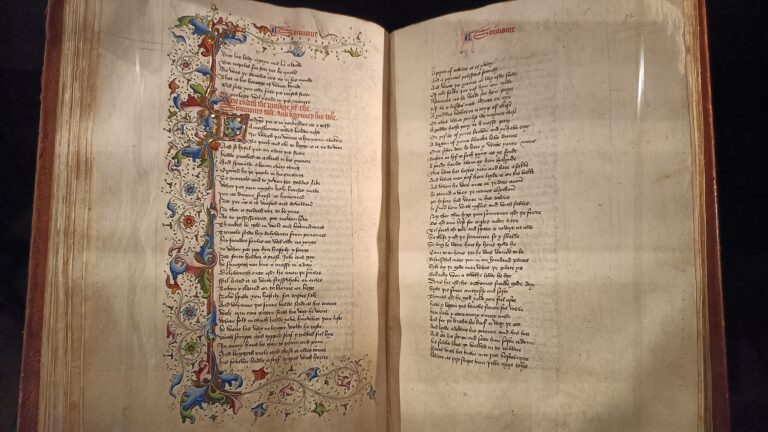

All books were tedious medieval projects. And according to the first quantitative review, some of them were written by women.

Experts estimate medieval scribes who produced more than 10 million manuscripts between 400 and 1500 CE, each of which is painstakingly copied, drawn and bound by their hands. Even today there are only about 750,000, but there is still much to learn from the surviving artifacts and the artisans who created them. But most books were written by monks, who were stuck on the desk for hours at a time on the screenplay desk of a monastery, but that was not always the case. The impressive historical revisions are detailed by researchers at the University of Bergen in Norway in a study published last month. Humanities and Social Sciences Communication.

The author noted that previous studies have examined the role of gender in the scripts of monasteries, but no one tried to calculate how many women contributed to these intense ventures. To begin their research, the team relied on a common section found in most medieval manuscripts called the Colophone. The scribe, an ostensibly biographer of the publisher, recorded his name at the end of the book, including the Colophone, and included a production date, sometimes a short statement of reflection, commissioned the project.

First, the researchers turned to the Benedictine Colophone’s existing catalogue and reviewed all 23,774 entries for gender language verification. A total of 254 are linked to female scribes, with 204 featuring the women’s own names. This amounts to about 1.1% of the books in the Benedictine database.

“Using existing estimates of manuscript production and losses, we might assume that at least 110,000 manuscripts have been copied by female scribes under the assumption that the estimates are valid.

The conservative number warned that researchers warned that their estimates were lower than the actual total. Many women may have deliberately omitted gender or names on the colophone, or simply did not include them at all. Meanwhile, it is possible that the survival rates of manuscripts that change across regions may have skewed the data.

One thing is almost certain. The number of known female scripturea listed in existing records may have failed to produce all of the manuscripts mediated by an estimated 110,000 women. For this reason, the team believes the survey “strongly suggests that there is a book-producing community of women that has not yet been identified.” Another possibility is that there could have been “more female scribes” than we thought.

“Our research should be seen as the first step to opening new perspectives,” the author writes.