An international team of scientists has developed a new class of compounds that can cure bacterial infections in mice, some of which cause a serious “flesh-eating” disease. 700-1,100 items Meat-related diseases cause 1 million deaths in the United States each year. This new class of compounds represents the beginning of a new class of antibiotics. The study was published in the journal Nature on August 2nd. Scientific advances.

Growing Resistance

For decades, clinicians have sounded the alarm about pathogens that are becoming increasingly resistant to currently available drugs, making them more dangerous and, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections Every year in the United States, 35,000 people died To protect bacteria from these infections, new antibacterial compounds are needed to replace those to which bacteria have become resistant.

The study was led by molecular microbiologists Scott Hultgren and Michael Capalone at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and chemist Fredrik Almqvist at Umeå University in Sweden. A new class of compounds called GmPcides.

[Related: These flesh-eating bacteria are finding new beaches to call home.]

GmPcides act in a targeted manner Gram-positive bacteriaThese types of bacteria can cause a variety of drug-resistant staphylococcal infections, toxic shock syndrome, and other bacterial diseases that can be fatal.

“All the gram-positive bacteria we tested were sensitive to this compound, including enterococci, staphylococci and streptococci. Clostridium difficilea major pathogenic bacterial species.” Capalone said in a statement.t. “This compound exhibits broad-spectrum activity against a large number of bacteria.”

“A happy coincidence”

The new GmPcide compounds are A type of molecule called ring-fused 2-pyridone This was developed by what the team calls a happy accident: Capalone and Hultgren asked Almqvist to develop a compound that would prevent bacterial membranes from adhering to the surface of urinary catheters, a common Causes of urinary tract infections in hospitals.

The resulting compound also had infection-fighting properties against multiple types of bacteria. Some of their previous work had shown that GmPcides could kill bacterial strains in petri dish experiments.

this New ResearchThe researchers took their petri dish experiments a step further, testing how their compounds would work on necrotizing soft-tissue infections, which spread quickly and typically involve multiple species of gram-positive bacteria. Necrotizing fasciitisFlesh disease is the best known of these infections, as it rapidly damages tissue and often requires amputation of limbs to contain its spread. 20 percent of patients He dies from flesh-eating disease.

The research team focused on one pathogen that causes about half a million deaths each year.Streptococcus pyogenesA group of mice was infected S. pyogenes. One group was treated with GmPcide, the other group was not. The GmPcide-treated mice fared better than the untreated mice by almost every criterion: they lost less weight, had smaller ulcers, and fought off the infection faster. Areas of damaged skin after infection also seemed to heal more quickly.

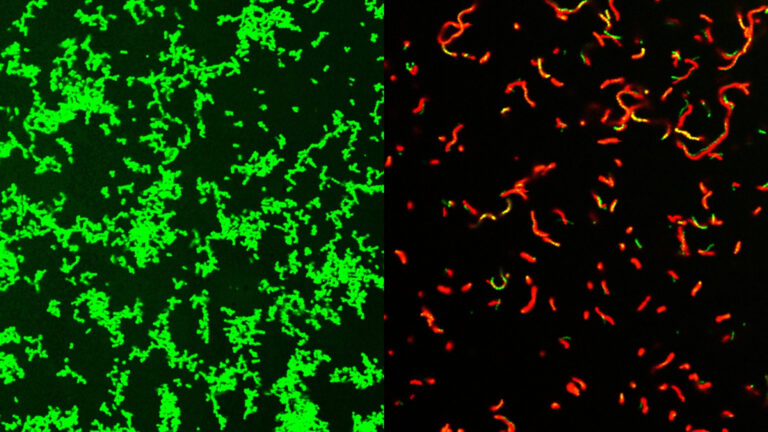

How GmPcides achieves all this is still not fully understood, but microscopy shows that the treatment has a profound effect on the bacterial cell membrane, which is the outer envelope of microorganisms.

[Related: ‘Bacterial glitter’ shimmers without pigments.]

“One of the roles of membranes is to keep out foreign substances,” Caparon says, “and we found that within 5 to 10 minutes of treatment with GmPcide, the membrane became permeable, allowing substances that would normally be kept out to get into the bacteria, indicating that the membrane had been damaged.”

This can alter the function of the bacteria itself, either by causing damage to the host or by reducing the bacteria’s ability to suppress the host’s immune response to infection.

GmPcides may also be less likely to produce drug-resistant bacteria: Experiments designed to create resistant bacteria found that only a few cells could survive the treatment, meaning they were less likely to pass on the advantage to the next generation of bacteria.

The Road Ahead

Capalone said there are still many steps to go before GmPcides can be purchased at your local pharmacy. The team has patented the compound they used and licensed it to QureTech Bio. Capalon, Hultgren and AlmqvistThe license was contingent on the expectation that it would work with another company that could manage drug development and clinical trials and bring it to market.

The team says collaborative science and technology, like the one that developed GmPcides, will be needed to treat problems such as antibiotic resistance.

“Bacterial infections of all kinds are a major health problem, with multidrug-resistant bacteria on the rise and becoming increasingly difficult to treat.” Hultgren said in a statement.“Interdisciplinary science can foster the integration of different research fields and lead to synergistic new ideas that may help patients.”