original version of this story Appeared in Quanta Magazine.

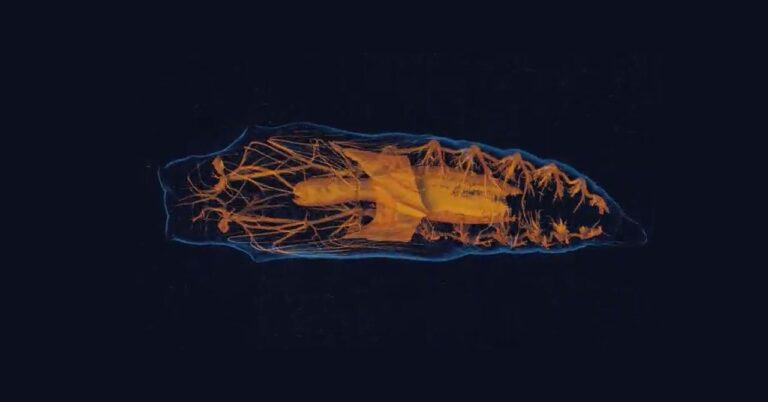

On warm summer nights, green lacewings fly around bright lanterns in backyards and campgrounds. These insects have veil-like wings that easily distract them from their primary focus: sipping on flower nectar, avoiding predatory bats, and reproducing. The tiny clusters of eggs they lay hang from long stalks on the underside of the leaves, swaying like fairy lights in the breeze.

A collection of hanging eggs is not only beautiful, but also practical. This prevents hatched larvae from eating their unhatched siblings too quickly. He said lacewing larvae are “vicious” as they pierce and suck out their prey with their sickle-like jaws. james truman, Professor Emeritus of Developmental, Cellular and Molecular Biology at the University of Washington. “It’s like “Beauty and the Beast” in one animal.”

This Jekyll and Hyde dichotomy is made possible by metamorphosis, a phenomenon best known for the transformation of caterpillars into butterflies. In the most extreme version, complete metamorphosis, juveniles and adults look and behave like completely different species. Metamorphosis is no exception in the animal kingdom. That’s pretty much a rule. 80% or more Animal species known today, primarily insects, amphibians, and marine invertebrates, undergo some form of metamorphosis or have complex multistage life cycles.

There are many mysteries surrounding the process of metamorphosis, but some of the most puzzling mysteries center on the nervous system. At the heart of this phenomenon is the brain, which must encode not one but several different identities. After all, the life of an insect flying in search of a mate is very different from that of a hungry caterpillar. Over the past half-century, researchers have discovered that the network of neurons that encodes one identity (the identity of a hungry caterpillar or a ferocious lacewing larva) can be transformed into an adult identity that encompasses a completely different set of behaviors and needs. We have been investigating the question of how to change it to encode it. .

Truman and his team have now determined the extent to which parts of the brain are replaced during metamorphosis.in recent research It was published in the magazine e-lifeThey tracked dozens of neurons in the fruit fly brain as it underwent metamorphosis. Researchers found that unlike the suffering protagonist of Franz Kafka’s short story “The Metamorphosis,” who wakes up one day as a giant insect, adults likely have little memory of their larval stages. discovered. Although many of the neurons in the larvae included in the study survived, the parts of the insect brains Truman’s group examined were dramatically rewired. This overhaul of neural connections reflected an equally dramatic behavioral shift as insects transform from crawling, hungry larvae to flying, mate-seeking adults.

They said their findings were “the most detailed example yet” of what happens to the insect brain during metamorphosis. Deniz Elegilmaz, a postdoctoral fellow in the Center for Neural Circuits and Behavior at the University of Oxford, previously worked in Truman’s lab but was not involved in this study. The results may apply to many other species on Earth, she added.