Because the Utah Array penetrates tissue, it can cause inflammation and scarring around the implantation site, which leads to decreased signal quality over time. Also, signal quality is important as it affects her BCI performance. No one really knows how long Utah sequences can persist in the brain. So far this record is held by Nathan Copeland, his device is now in its eighth year.

Placing the Utah array also requires the surgeon to perform a craniotomy to drill a small hole in the skull. This is a major surgery that can lead to infections and bleeding, and recovery can take a month or more. Naturally, many patients may be reluctant to seek treatment, even if it means regaining some degree of communication and mobility.

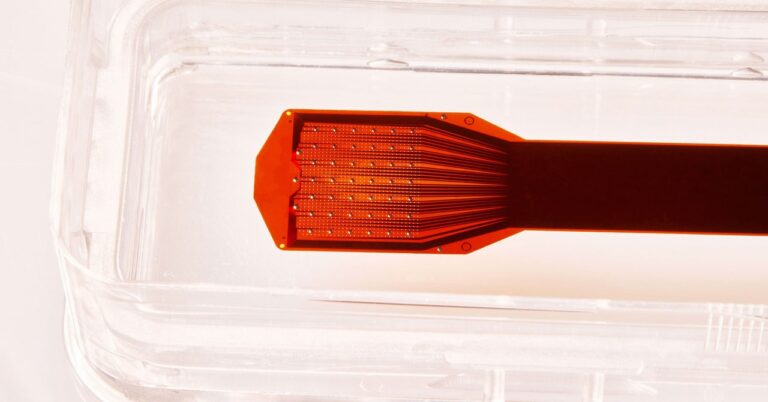

Precision is trying to solve both problems with a device that has 1,024 electrodes but is ultra-thin, about one-fifth the thickness of a human hair, so it won’t pierce brain tissue. Instead of a craniotomy, it’s a minimally invasive procedure that involves making a small slit in the skin and skull and sliding the implant into the outermost layer of the brain, called the cortex. “The very idea of doing more damage to an already damaged brain or nervous system is very challenging,” says Rapoport, who also co-founded Neuralink. He believes streamlining the procedure will make these systems even more attractive to patients.

The company’s president and chief product officer, Craig Murmell, says the Precision array is just as easy to pull out. As BCI technology improves, patients who obtained early brain chips may eventually want to upgrade to newer brain chips. Utah arrays typically cannot place new devices in the same area because of scar tissue.

With more than 1,000 electrodes, Precision’s device will be able to capture brain activity at a higher resolution than current arrays, Mermel said. Precision arrays are also designed to be modular. Several can be connected to collect brain signals from larger areas. Beyond stimulating basic body movements and triggering simple computer functions, “you’ll need to cover more areas of the brain” to perform more precise and complex actions. says Marmell.

Precision’s implants look great, but it’s still unclear how long they’ll last once they’re implanted, said Peter Brunner, associate professor of neurosurgery and biomedical engineering at Washington University in St. Louis. Devices implanted in the body tend to degrade over time. “There is a tension between miniaturization and at the same time maintaining robustness for the environments these devices will face inside the human body,” he says.

The brain migrates within the skull, and implants may migrate as well, Brunner said. Surface arrays may travel around multiple arrays penetrating the brain. Even a micrometer shift, he said, could change the group of neurons the device is recording, which could affect how the BCI works.

All electrodes move slightly over time, Rapoport said, but Precision’s software that decodes nerve signals can accommodate these small changes.