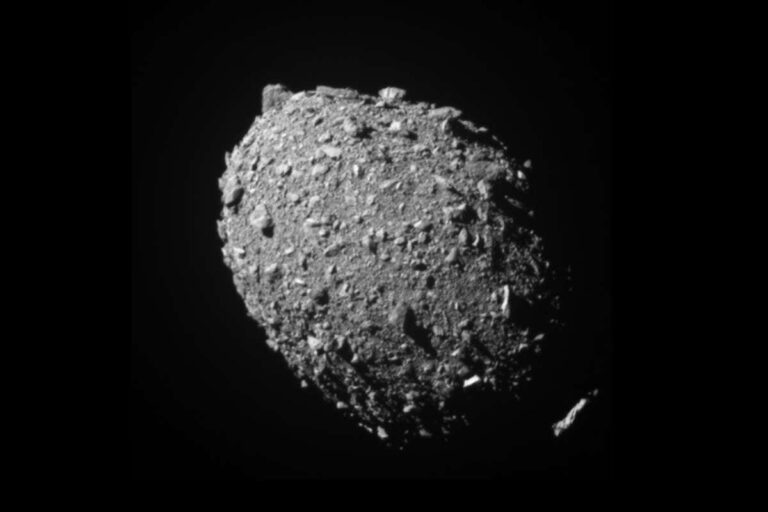

Asteroid Dimorphos as seen by the DART spacecraft 11 seconds before impact

NASA/Johns Hopkins APL

NASA tried to slam a spacecraft into an asteroid in 2022 to get it moving, but the collision had more than expected effects on the asteroid’s trajectory. Analysis of the wreck and its aftermath may reveal why, and the results may tell us even more about how to protect Earth from asteroids.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) sent a probe cairning to a small asteroid called Dimorphos orbiting a larger asteroid called Didymos. Five research groups analyzed different aspects of the collision and found that Dimorphus was closer to Didymos, all trajectories about 33 minutes shorter than before the collision. This is more than 25 times the orbital period change required for the mission to be considered successful. .

That was helped by the fact that DART was spot on. “The spacecraft hit the center of Dimorphus very close, and we want to hit it there to maximize momentum transfer,” he says. carolyn ernst at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland.

But perhaps more importantly, part of the asteroid flew away after impact, giving it extra power. “People might think of the DART mission as a fairly simple experiment, akin to playing billiards in space: one solid spacecraft crashing into his one solid asteroid,” he said. say. Christina Thomas at Northern Arizona University. “But asteroids are much more complex than just solid rock.”

After all, most asteroids, including Dimorphus, are heaps of rubble tenuously held together by gravity. So when DART hit, 0.3-0.5% of the asteroid’s mass was ejected into a giant ejecta. This plume amplified the momentum transferred from the spacecraft to the asteroid by a factor of 3.6.

If you need to use something like DART to deflect an asteroid heading towards Earth, you need to understand that the extra push will be important. “Ejecta will give the asteroid more force than the spacecraft itself, so if we need to use this technology to avoid an asteroid hitting Earth in the future, we won’t necessarily need a huge spacecraft. No.” says Jiangyan Lee at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona.

The ejecta plume also places Dimorphus in a strange category of asteroids called active asteroids with comet-like tails. It has long been thought that these tails could form from collisions with smaller cosmic rocks, and DART has shown that idea fits nicely. We can now pinpoint what’s going on in the .” Ariel Greikowski at the SETI Institute in California.

We know that after DART we can change the orbits of smaller asteroids like Dimorphus, but since asteroids are all different, would a similar mission work against anything that might be headed in our direction? “I think the best way to apply what we’ve learned is to apply it again to something bigger,” says Graykowski. “We need to take advantage of what we know about how squishy the asteroid ended up being, how much material it ejected, how much it could move, whether it could be scaled up and started all over again. there is.”

Journal reference: Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05805-2, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05810-5, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05811-4, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05878-z, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05852-9

Sign up for our free monthly Launchpad newsletter and embark on a journey to the galaxy and beyond

topic: